Treatment Outcomes in Patients Receiving Regorafenib for Metastatic Colon Cancer

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Treatment Outcomes in Patients Receiving Regorafenib for

Metastatic Colon Cancer

L Fok, KM Cheung, YL Kwok, KH Wong

Department of Clinical Oncology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong

Correspondence: Dr L Fok, Department of Clinical Oncology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Jordan, Hong Kong. Email: leslie.fok@link.cuhk.edu.hk

Submitted: 7 Jun 2019; Accepted: 3 Sep 2019.

Contributors: LF and KMC designed the study and acquired the data. All authors contributed to the analysis of data, drafted the manuscript,

and had critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study,

approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (Kowloon Central/Kowloon East) of the Hospital Authority,

Hong Kong (Ref KC/KE-19-0046-ER/4). The requirement for patient consent was waived. All patients were treated in compliance with the

Declaration of Helsinki.

Abstract

Introduction

To review the treatment outcomes of patients with chemorefractory metastatic colorectal cancer receiving the multikinase inhibitor regorafenib.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study including patients who received regorafenib after failure of standard

irinotecan- and oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy with or without biologics from 2016 to 2018 in a single centre in

Hong Kong.

Results

Fourteen patients met the inclusion criteria. All had good general condition (i.e., Eastern Cooperative

Oncology Group score 1). Seven patients had received bevacizumab previously. Median progression-free survival

(PFS) was 12.4 weeks and median overall survival (OS) was 26.5 weeks. Eight patients had grade ≥3 adverse events

and 10 (71.4%) required temporary treatment suspension. The commonest grade ≥3 adverse events were palmar-plantar

erythrodysaesthesia and fatigue (both 28.6%). Patients with a carcinoembryonic antigen drop of ≥50% from

baseline enjoyed longer PFS, though not to a significant extent. OS was longer for left-sided primary tumours (202

vs. 57 days, p = 0.001). Two patients with good performance after progression received trifluridine-tipiracil. Their

median OS was 400 days.

Conclusion

Our experience with regorafenib monotherapy for patients with chemorefractory metastatic colorectal

cancer was comparable to the landmark trials. The grade ≥3 adverse events were frequent, and dose reduction or

treatment delay was required. Potentially favourable prognostic factors included a left-sided primary tumour and

a carcinoembryonic antigen drop from baseline. Those who received further treatment after regorafenib enjoyed

reasonably long survival. Treatment after regorafenib with newer strategies should be considered in those who

remain functional.

Key Words: Colorectal neoplasms; Protein kinase inhibitors

中文摘要

瑞戈非尼對大腸癌轉移患者的治療結果

霍善智、張嘉文、郭婉琳、黃錦洪

目的

探討多激酶抑制劑瑞戈非尼對化療難治性大腸癌轉移患者的治療結果。

方法

這項回顧性隊列研究納入2016年至2018年於香港單一中心進行標準伊立替康和奧沙利鉑化療無效後接受瑞戈非尼治療合用或未合用生物製劑的患者。

結果

14名患者符合納入標準。所有患者的身體狀況較好(ECOG 1分),當中7名患者曾接受貝伐單抗治療。無惡化存活期中位數為12.4週,總體存活期中位數為26.5週。8名患者出現≥3級不良事件,10名患者(71.4%)須暫停治療。最常見≥3級不良事件包括掌足紅腫綜合徵和疲勞(均為28.6%)。癌胚抗原從基線下降≥50%的患者有更長無惡化存活期,但只有邊緣顯著性。左側原發腫瘤患者的總體存活期較長(202天比57天,p = 0.001)。兩名患者在瑞戈非尼治療失敗後因體能狀態較佳,遂以三氟胸苷—替吡嘧啶作進一步治療。他們的總體存活期中位數為400天。

結論

本研究的瑞戈非尼單藥治療化療難治性大腸癌轉移患者的經驗與具有里程碑意義的試驗相若。≥3級不良事件很常見,須減少劑量或延遲治療。潛在的有利預後因素包括左側原發腫瘤和癌胚抗原從基線下降。瑞戈非尼後接受進一步治療患者有較長存活期。使用瑞戈非尼後仍保持功能的患者,可考慮以新策略作進一步治療。

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is the commonest malignancy in Hong

Kong, with an age-standardised incidence rate of 35.7

per 100 000 population in 2016.[1] Up to 23% of patients

have metastatic disease on presentation, and the 5-year

overall survival (OS) is 14%.[2]

Traditionally, chemotherapy and biologics using

fluoropyrimidine, irinotecan and oxaliplatin, with or

without anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)

agents and anti–epithelial growth factor receptor

(EGFR) agents for RAS wild-type tumours, were the

main treatment strategies for inoperable or metastatic

colorectal cancer (mCRC). Despite the range of available

combination therapies, OS remained in the range of 20

to 30 months.[3] Options beyond these standard treatments

were limited, with regorafenib and trifluridine-tipiracil

being the only two Food and Drug Administration

(FDA)–approved treatments for this group of patients.[4]

Regorafenib is an oral multikinase inhibitor, which

is structurally similar to sorafenib. It blocks multiple

kinases involved in tumour angiogenesis (VEGFR 1-3,

Tie2), oncogenesis (KIT, RET, RAF1 and BRAF), and

tumour microenvironment (PDGFR and FGFR). In an

international multicentre phase III trial (CORRECT),

statistically significant, yet modest improvement in OS

was demonstrated compared with placebo in patients with colorectal cancer who had failed multiple lines

of chemotherapy (6.4 months vs. 5.0 months, hazard

ratio = 0.77, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.64-0.94,

p = 0.0052).[5] The results were similar in a subsequent

study targeting Asian populations.[6] However, grade 3

or 4 adverse events (AEs) were high in both trials and

in real-world settings,[7] affecting >50% of patients. The

modest magnitude of survival prolongation and its

significant toxicity suggests the importance of careful

patient selection and the urgency of identification of

additional treatment strategies. We aimed to review our

experience in using regorafenib monotherapy as a last-line

treatment, and to investigate predictive markers of

treatment response.

METHODS

Patients

This study was approved by the ethics committee of

Kowloon Central Cluster/Kowloon Eastern Cluster of the

Hospital Authority and conducted in compliance with the

Declaration of Helsinki. Records of patients with stage

IV colorectal adenocarcinoma who received regorafenib

from January 2016 to December 2018 in the Department

of Clinical Oncology of Queen Elizabeth Hospital

were retrieved and retrospectively analysed. Patients

were offered regorafenib after exhausting all available

treatments at that time, which included chemotherapy

fluoropyrimidine, irinotecan and oxaliplatin; and biologics with bevacizumab and cetuximab if clinically

suitable and affordable.

Treatment

Regorafenib was provided either on a compassionate

basis from the pharmaceutical company or as a selffinanced

item during the study period. Patients received

regorafenib 160 mg daily for the first 3 weeks of each

4-week cycle until disease progression, death, intolerable

AEs, or patients’ refusal to continue / inability to afford

treatment. Lower starting doses and dose reduction or

escalation during treatment were allowed per clinical

judgement of the prescribing physician.

Assessment

Patients were followed up fortnightly with routine

monitoring of complete blood counts, liver and renal

function tests, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)

levels. Interval computed tomography scanning was

arranged every 10 to 12 weeks. The RECIST (Response

Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumour) version 1.1 was

referred to in order to determine treatment response.

AEs were defined and graded according to the CTCAE

(Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events)

version 4.0 by National Cancer Institute. A CEA response

was defined as a decrease of CEA from baseline after the

start of regorafenib.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS

(Windows version 26.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY],

United States). Descriptive statistics on central tendency

(e.g., mean, median) and data dispersion (e.g., range,

standard deviation, 95% CI) were used. The Kaplan-

Meier method and log-rank test were used to depict

and analyse survival outcomes. A p value of <0.05 was

considered significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

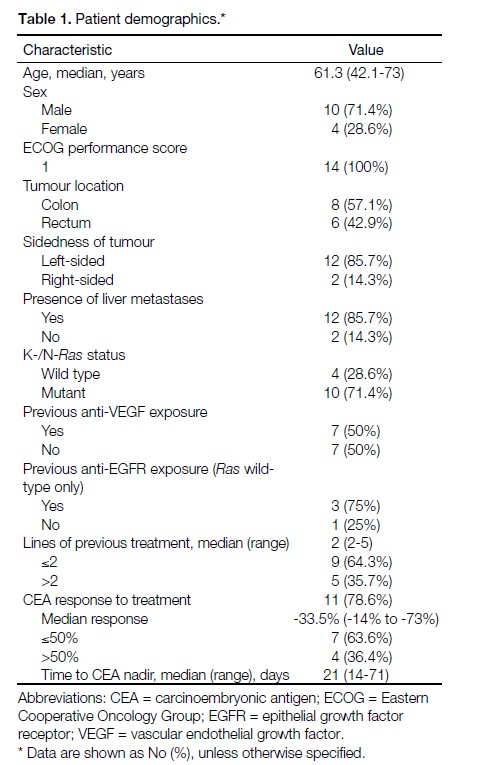

From January 2016 to December 2018, a total of 14

mCRC patients received regorafenib. Patient baseline

characteristics are summarised in Table 1. The median

age was 61.3 years. All patients had an Eastern

Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance

score of 1. In all, 57.1% of them had primary colon

cancer while the rest had primary rectal cancer. In total,

85.7% had liver metastases when regorafenib treatment

was initiated, and approximately 60% of them had

three or more metastatic sites. Approximately 70% of

the patients had K- or N-RAS mutant tumours. Half of the patients had undergone anti-VEGF therapy prior to starting regorafenib. In the RAS wild-type subgroup,

three (75%) of the patients had received an anti-EGFR

agent. One patient (25%) chose not to receive anti-EGFR

therapy due to affordability. The median number of lines

of systemic therapy before regorafenib was two. Only

two patients continued onto a next line of treatment

after failure of regorafenib. The rest either had died by

the time of progression (n = 2), were unfit for further

oncological treatment due to disease progression (n = 4),

or were unable to afford any more treatment (n = 6).

Table 1. Patient demographics.

Response

The median number of cycles of regorafenib received

was 2.67. The median dose intensity was 75% of the full

dose. Three patients achieved radiographically stable

disease, while the 11 others developed progressive

disease during regorafenib treatment. The overall

disease control rate was thus 21.4%. At the same time,

patients’ CEA response was analysed. All patients had

baseline CEA elevation (median CEA = 61; range, 8.3-1594). Eleven patients (78.6%) had a drop in CEA after

starting regorafenib. The median time to CEA nadir was

3 weeks and the median drop in CEA was 33.5% (range,

14%-73%). Using 50% as a cut-off, which was a value

also used in larger studies,13 seven (63.6%) of the CEA

responders had a drop in CEA ≤50%, while four (36.4%)

of them had a drop of >50%. No statistically significant

correlation was found between the degree of CEA drop

and the respective radiological response (Fisher’s exact

test, p = 1.00).

Tolerance

Average Time to Temporary Treatment Suspension

Ten patients (71.4%) required temporary treatment

suspension during their course of regorafenib due

to toxicities. The mean total time of suspension was

1.7 weeks, and the mean time of suspension per treatment

cycle was 4.9 days.

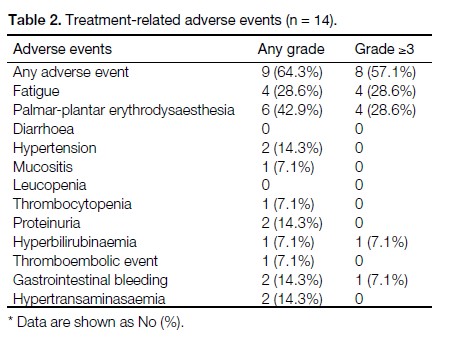

Adverse Events

Table 2 shows a summary of all the treatment-related

AEs. Nine patients (64.3%) experienced toxicity of

any kind and grade. Most AEs were severe, with eight

patients (57.1%) having grade ≥3 AEs. The most

common AEs were palmar-plantar erythrodysaesthesia

and fatigue (both 28.6%). Ten patients (71.4%) required

suspension at some point in their treatment.

Table 2. Treatment-related adverse events (n = 14).

Survival

Progression-free Survival

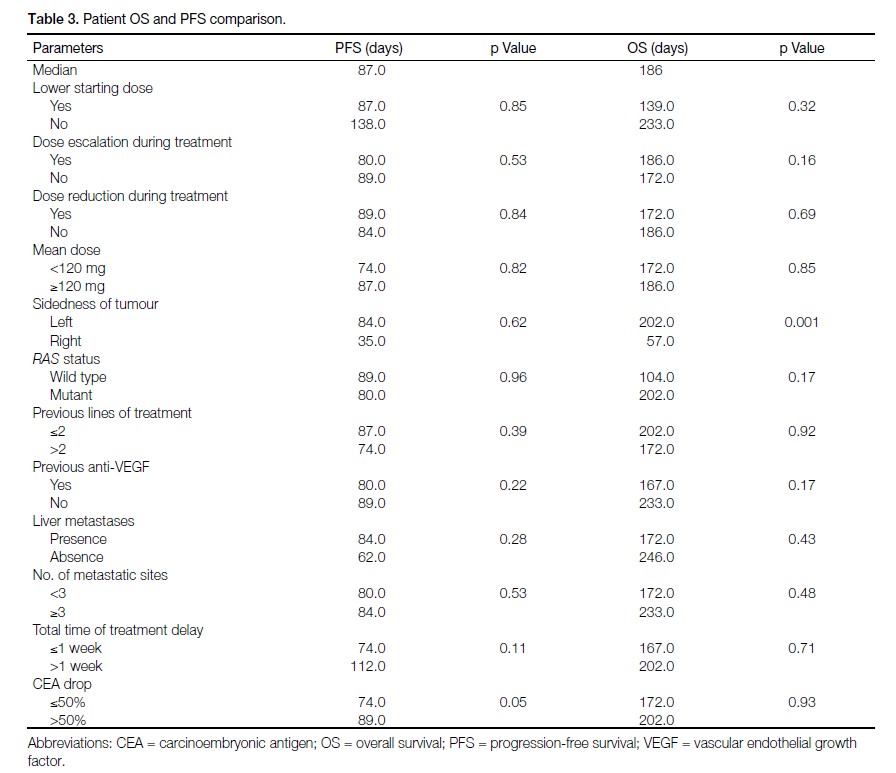

After a median follow-up of 194 days, disease progression

was noted in 13 patients. The median progression-free

survival (PFS) was 87 days (95% CI = 81.3-92.6 days).

In univariate analysis, PFS was not significantly worse

for patients with a lower regorafenib starting dose or who

required dose reduction (n = 4), nor was it associated

with mean delay per cycle or the mean dose throughout

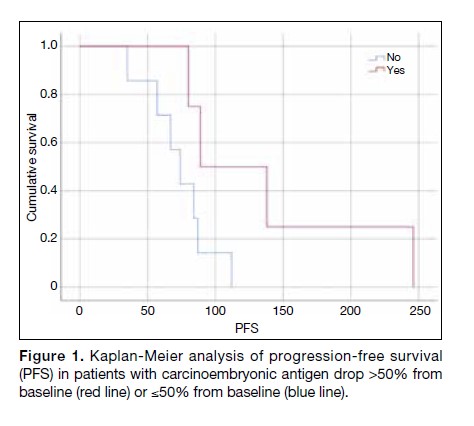

treatment (Table 3). The association between a >50%

decrease in CEA and better PFS was not significant

(89 vs. 74 days, p = 0.05) [Figure 1].

Table 3. Patient OS and PFS comparison.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier analysis of progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with carcinoembryonic antigen drop >50% from

baseline (red line) or ≤50% from baseline (blue line).

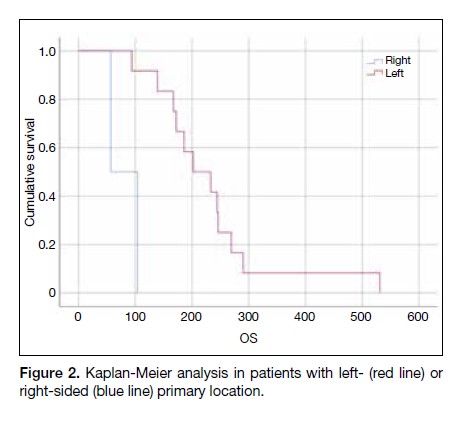

Overall Survival

The median OS was 186 days (95% CI = 131-241 days).

Patients with left-sided tumours had longer OS when

compared with those with right-sided tumours (202 vs.

57 days, p = 0.001) [Figure 2]. No other factors were

significantly associated with OS (Table 3).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier analysis in patients with left- (red line) or

right-sided (blue line) primary location.

Subsequent Treatment

Only two (14%) of the patients had satisfactory World

Health Organization performance status (i.e., ECOG

score 1) and were able to afford and undergo further

treatment after disease progression. All of them received

trifluridine-tipiracil (Lonsurf; Taiho Oncology, Japan)

after regorafenib. Their survivals after regorafenib were

207 and 464 days, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Regorafenib is one of the few treatment options available

for mCRC that has failed oxaliplatin- and irinotecan-based

chemotherapy. In two large international

randomised controlled phase III studies, CORRECT5

and CONCUR,6 the median PFS was approximately 60.9

to 91.3 days, and the OS was approximately 197.8 to 273.9 days. In the current study, the median PFS was

87 days (95% CI = 81.3-92.6 days) and the median

OS was 186 days (95% CI = 131-241 days), which are

comparable to these two phase III studies.

AEs remain a concern in treatment with regorafenib. In

both the CORRECT and CONCUR trials, 54% of the

patients experienced grade ≥3 AEs,5,6 which are similar

to our study (57.1%). The most common AE in our study

was palmar-plantar erythrodysaesthesia, with >40% of

patients affected. Approximately two-thirds of these

patients had grade ≥3 palmar-plantar erythrodysaesthesia,

which commonly led to treatment suspension. Although

only 28.6% of the patients experienced fatigue, all of

them reported grade 3 fatigue (fatigue limiting self-care)

during the course of treatment. The occurrence of fatigue in trials varies considerably. In the CONCUR trial, only

17% of patients reported fatigue of any grade and only

2.9% had fatigue of grade ≥3.6 In contrast, 48% of

patients experienced fatigue in the CORRECT trial, with

9.6% of them having fatigue grade ≥3.5 In a systematic

review, the incidence of fatigue ranges from 2% to 73%

in different studies.[8]

As regorafenib is associated with significant rates of

AEs when used at full dose, the optimisation of dosing

and schedule is a widely discussed topic. From our data,

intercycle delay was common, with >70% of patients

experiencing a mean of 4.9 days of delay per treatment

cycle due to AEs, but without a statistically significant

impact on survival outcome. The PFS and OS for lower

starting doses were shorter than those of the usual

starting dose, but not significantly shorter. Outcomes also

appeared to be independent of dosing strategies (interval

dose reduction or interval dose escalation). In ReDOS,

a randomised phase II study, patients were randomised

to receive a starting dose of 80 mg with subsequent

dose escalation, or a standard starting dose of 160 mg.

The survival outcomes were not significantly different.[9]

While the small sample size limits robust statistical

inference, our data concur with the latest evidence. As the

slow dose escalation approach appears to result in better

tolerability and safety, we expect it to gain popularity

in the near future. Other strategies on management of

AEs have also been explored, though efficacy is limited.

For example, for treatment-related fatigue, one phase II

study investigated the effect of dexamethasone on these

patients but failed to show any improvement.[10]

Currently there is no established marker to predict the

treatment response towards regorafenib. In our study,

patients with left-sided tumours enjoyed longer OS,

which concurs with the findings of many other studies

that left-sided tumours carry a better prognosis regardless

of treatment, stage, race of patients, or length of study.[11]

Some retrospective studies also suggest that in addition

to its prognostic implications, primary tumour location

may be a predictive factor for treatment response in the

first-line setting.[12] Whether such predictive value also

applies to regorafenib warrants further study.

Although not significant, our results showed a marginal

association between drop in CEA and PFS. The median

time to CEA nadir was found to be 3 weeks. There is

no strong evidence on how the degree of CEA decrease

correlates with clinical response, and most studies have

used arbitrary cut-offs for CEA analysis. We used 50% as an arbitrary cut-off, which was a value also used in

larger studies.[13] As most of the CEA responders only

achieved stable disease in radiological assessment, it may

be suggested that the benefit observed in patients with

a drop in CEA of >50% is independent of radiological

response. The absolute reading of CEA is known to

reflect tumour burden and carries a prognostic value in

patients with mCRC, and was reported to have a role

in predicting treatment failure in the absence of readily

measurable disease response.[14] Further verification is

needed in a prospective manner to evaluate its prognostic

value.

Treatment beyond regorafenib is limited and no clinical

guidelines suggest an agreed-upon next line of treatment,

although trifluridine-tipiracil (Lonsurf), the other drug

licensed for use in refractory mCRC, is a frequent

treatment of choice. In our study, only two patients

underwent further treatment with trifluridine-tipiracil,

and the survival time was considerably long (median,

400 days). Trifluridine-tipiracil consists of a nucleoside

analogue (trifluridine) and a thymidine phosphorylase

inhibitor (tipiracil) which causes DNA strand breaks.[15]

The different mode of action may explain the longer

disease control in patients who have failed regorafenib.

Treatment after regorafenib rather than best supportive

care is therefore a reasonable option provided that

patients are still fit for systemic treatment.

A number of limitations of this study should be

acknowledged. First, the eligible population was small

(n = 14) as only a proportion of patients remained

fit for further treatment after failing multiple lines of

chemotherapy. The considerable cost of regorafenib (a

self-financed item) also limited the number of eligible

patients. As a result, it can only be deduced that there was

a tendency suggesting that good response of CEA and a

left-sided primary tumour were favourable prognostic

factors in patients using regorafenib, and this should be

verified in a larger prospective study. Second, the cut-off

used for CEA analysis was arbitrary, without verification

by prospective data. Finally, the report of toxicity

outcomes is also compromised by its retrospective nature

and the subjectivity of toxicities like fatigue.

With the advancements in molecular studies, more

options will be available for patients with mCRC who

have run out of treatment choices. The BRAF mutation

is found in approximately 5% to 10% of patients with

mCRC.[16] It is known to carry a poor prognosis,[17] and

is a predictive factor for poor response to anti-EGFR therapy in RAS wild-type patients,[18]18 so much so that

established international guidelines do not recommend

anti-EGFR therapy in patients who harbour the BRAF

mutation.[19] Among these patients, monotherapy with the

BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib failed to show a meaningful

activity in BRAFV600E-mutated mCRC.[20] In a phase I/II

open-label study, more than half of the study population

achieved a stable disease after a combination of the BRAF

inhibitor daBRAFenib, and the MEK inhibitor trametinib.

The overall response rate was 12% and the median PFS

was 3.5 months (95% CI = 3.4-4.0 months).[21] Immune

checkpoint inhibitors have been shown to benefit

patients with deficient mismatch repair (dMMR), which

is characterised by a high number of DNA replication

errors and high levels of DNA microsatellite instability.

The dMMR tumours are present in approximately 5%

of patients with mCRC[22] and are known to carry a poor

prognosis, which is driven by its association with the

BRAF mutation.[17] In a phase II study looking at the use

of pembrolizumab in patients with mCRC, an objective

response rate (ORR) of 50% was achieved in patients

with dMMR, while none was achieved in patients with

proficient mismatch repair.[23] OS and PFS have not

been reached for patients with dMMR, whereas the

OS was 7.6 months and the PFS was 2.3 months for

patients with proficient mismatch repair. As a result,

pembrolizumab has been granted an indication by the

FDA for its use in colorectal cancer that has progressed

following treatment with a fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin,

and irinotecan without satisfactory alternative treatment

options. Nivolumab, a monoclonal antibody against

programmed cell death protein 1, is another option

for patients with dMMR. In the CheckMate 142 trial

that looked at nivolumab ± ipilimumab, a monoclonal

antibody against cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4, in

heavily pretreated patients with mCRC, the ORR with

nivolumab monotherapy was 31.1%.[22] It was even

higher in the nivolumab plus ipilimumab group with an

ORR of 55%. Grade 3 to 4 toxicities were observed in

20% in the monotherapy group, and 29% in the doublet

group.[24] Based on these results, FDA indications have

been granted for the use of nivolumab in patients with

dMMR who have failed a fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin,

and irinotecan; and for the use of nivolumab plus

ipilimumab for patients with previously treated dMMR

mCRC.

In patients with unclear dMMR status, addition of

nivolumab to regorafenib has been investigated in

REGONIVO, a phase IB study. This strategy yielded

an ORR of 38% in the unselected population, and an even higher response in patients with microsatellite

instability–high CRC (44%).[25] When used with

nivolumab, reduction of the starting dose of regorafenib

to 80 mg rendered this regimen more tolerable.

CONCLUSION

Treatments for mCRC after oxaliplatin- and irinotecanbased

chemotherapy remain limited. Our institutional

experience with regorafenib was generally consistent

with the available literature. Our study also found that

there is a tendency towards a longer duration of stable

disease in patients with an initial drop of CEA after

starting regorafenib and a left-sided primary tumour.

Treatment beyond regorafenib in those who remain

medically fit and are able to afford more treatment

resulted in a favourable OS. With the promise of

novel agents shown to be highly effective in selected

populations, and their overall favourable toxicity profile,

further prospective studies are warranted.

REFERENCES

Hong Kong Cancer Registry, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR Government. 2016. Available from: https://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg Accessed 24 Apr 2019.

2. National Cancer Institute, Department of Health and Human Service, US Government. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program Research Data (1975-2016), National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program. Available from: https://www.seer.cancer.gov. Accessed 1 Jun 2019.

3. Jawed I, Wilkerson J, Prasad V, Duffy AG, Fojo T. Colorectal cancer survival gains and novel treatment regimens: a systematic review and analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:787-95. Crossref

4. Yoshino T, Arnold D, Taniguchi H, Pentheroudakis G, Yamazaki K, Xu RH, et al. Pan-Asian adapted ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a JSMO-ESMO initiative endorsed by CSCO, KACO, MOS, SSO and TOS. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:44-70. Crossref

5. Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero A, Siena S, Falcone A, Ychou M, et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:303-12. Crossref

6. Li J, Qin S, Xu R, Yau TC, Ma B, Pan H, et al. Regorafenib plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care in Asian patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CONCUR): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:619-29. Crossref

7. Lam KO, Lee KC, Chiu J, Lee VH, Leung R, Choy TS, et al. The real-world use of regorafenib for metastatic colorectal cancer: multicentre analysis of treatment pattern and outcomes in Hong Kong. Postgrad Med J. 2017;93:395-400. Crossref

8. Røed Skårderud M, Polk A, Kjeldgaard Vistisen K, Larsen FO, Nielsen DL. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;62:61-73. Crossref

9. Bekaii-Saab TS, Ou FS, Ahn DH, Boland PM, Ciombor KK, Heying EN, et al. Regorafenib dose-optimisation in patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer (ReDOS): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1070-82. Crossref

10. Tanioka H, Miyamoto Y, Tsuji A, Assayama M, Shiraishi T, Yuki S, et al. Prophylactic effect of dexamethasone on regorafenib-related fatigue and/or malaise: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical study in patients with unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer (KSCC1402/HGCSG1402). Oncology. 2018;94:289-96. Crossref

11. Petrelli F, Tomasello G, Borgonovo K, Ghidini M, Turati L Dallera P, et al. Prognostic survival associated with left-sided vs right-sided colon cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:211-9. Crossref

12. Holch JW, Ricard I, Stintzing S, Modest DP, Heinemann V. The relevance of primary tumour location in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of first-line clinical trials. Eur J Cancer. 2017;70:87-98. Crossref

13. Aggarwal C, Meropol NJ, Punt CJ, Iannotti N, Saidman BH, Sabbath KD, et al. Relationship among circulating tumor cells, CEA and overall survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:420-8. Crossref

14. Clinical practice guidelines for the use of tumor markers in breast and colorectal cancer. Adopted on May 17, 1996 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology [editorial]. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2843-77. Crossref

15. Lenz HJ, Stintzing S, Loupakis F. TAS-102, a novel antitumor agent: a review of the mechanism of action. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41:777-83. Crossref

16. Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949-54. Crossref

17. Tran B, Kopetz S, Tie J, Gibbs P, Jiang ZQ, Lieu CH, et al. Impact of BRAF mutation and microsatellite instability on the pattern of metastatic spread and prognosis in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:4623-32. Crossref

18. Rowland A, Dias MM, Wiese MD, Kichenadasse G, McKinnon RA, Karapetis CS, et al. Meta-analysis of BRAF mutation as a predictive biomarker of benefit from anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody therapy for RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:1888-94. Crossref

19. Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, Sobrero A, Van Krieken JH, Aderka D, et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1386-422. Crossref

20. Kopetz S, Desai J, Chan E, Hecht JR, O’Dwyer PJ, Maru D, et al. Phase II pilot study of vemurafenib in patients with metastatic BRAF-mutated colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:4032-8. Crossref

21. Corcoran RB, Atreya CE, Falchook GS, Kwak EL Ryan DP, Bendell JC, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition with daBRAFenib and trametinib in BRAFV600-mutant colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:4023-31. Crossref

22. Overman MJ, McDermott R, Leach JL, Lonardi S, Lenz HJ, Morse MA, et al. Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair-deficient or microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer (CheckMate 142): an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1182-91. Crossref

23. Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509-20. Crossref

24. Overman MJ, Lonardi S, Wong KY, Lenz HJ, Gelsomino F, Aglietta M, et al. Durable clinical benefit with nivolumab plus ipilimumab in DNA mismatch repair-deficient/microsatellite instability-high metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:773-9. Crossref

25. Fukuoka S, Hara H, Takahashi N, Kojima T, Kawazoe A, Asayama M, et al. Regorafenib plus nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric (GC) or colorectal cancer (CRC): An open-label, dose-finding, and dose-expansion phase 1b trial (REGONIVO, EPOC1603). J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15 suppl):2522. Crossref