Inverted Meckel’s Diverticulum — A Rare Complication of a Common Congenital Anomaly: A Case Report

CASE REPORT

Inverted Meckel’s Diverticulum — A Rare Complication of a

Common Congenital Anomaly: A Case Report

KKF Fung1; JHF Chiu2; KK Cheng1

1 Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Yaumatei, Hong Kong

2 Department of Surgery, Kwong Wah Hospital, Yaumatei, Hong Kong

Correspondence: Dr KKF Fung, Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Yaumatei, Hong Kong. Email: gwevin@gmail.com

Submitted: 15 Jul 2018; Accepted: 10 Aug 2018.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the concept of study, acquisition and analysis of data, drafting of the manuscript, and had critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Approval: Informed consent was obtained from the patient. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki

INTRODUCTION

Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common congenital

anomaly of the gastrointestinal tract and found in

approximately 2% of the population. Most Meckel’s

diverticula remain clinically silent with an estimated

lifetime risk of complications reported to be about

4% to 40%.[1] Inversion of Meckel’s diverticulum is a

rare phenomenon that occurs when the diverticulum

invaginates upon itself into the lumen of the terminal

ileum. This can be further complicated by small bowel

haemorrhage and intussusception, where the inverted

diverticulum acts as a lead point.[2] We describe a case

of inverted Meckel’s diverticulum presenting with acute

small bowel haemorrhage.

CASE REPORT

A 43-year-old man presented with a 2-week history

of recurrent central abdominal pain and an episode of

haematochezia. On admission, he was clinically stable

and clinical examination did not reveal any mass or

tenderness in the abdomen. Per rectal examination found

a trace amount of fresh blood. However, six episodes of

massive fresh per rectal bleeding developed subsequently

with a witnessed episode of syncope. Haemoglobin dropped from 94 g/L on admission to 63 g/L and urgent

oesophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy were

performed. No obvious source of bleeding could be

identified although a large amount of old blood product

was seen in the terminal ileum on colonoscopy, raising a

suspicion of small bowel haemorrhage.

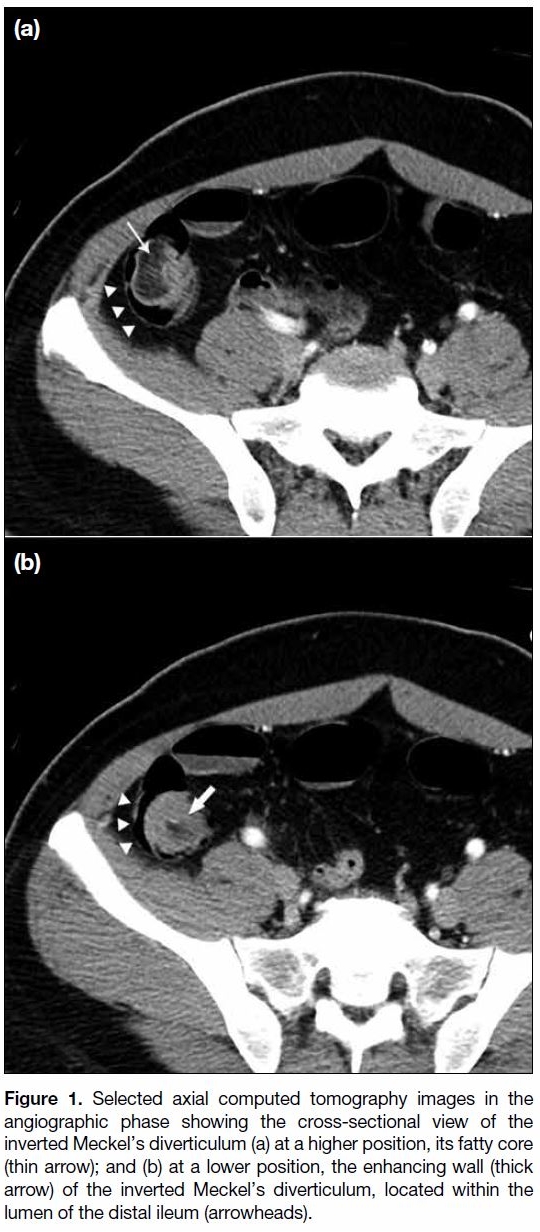

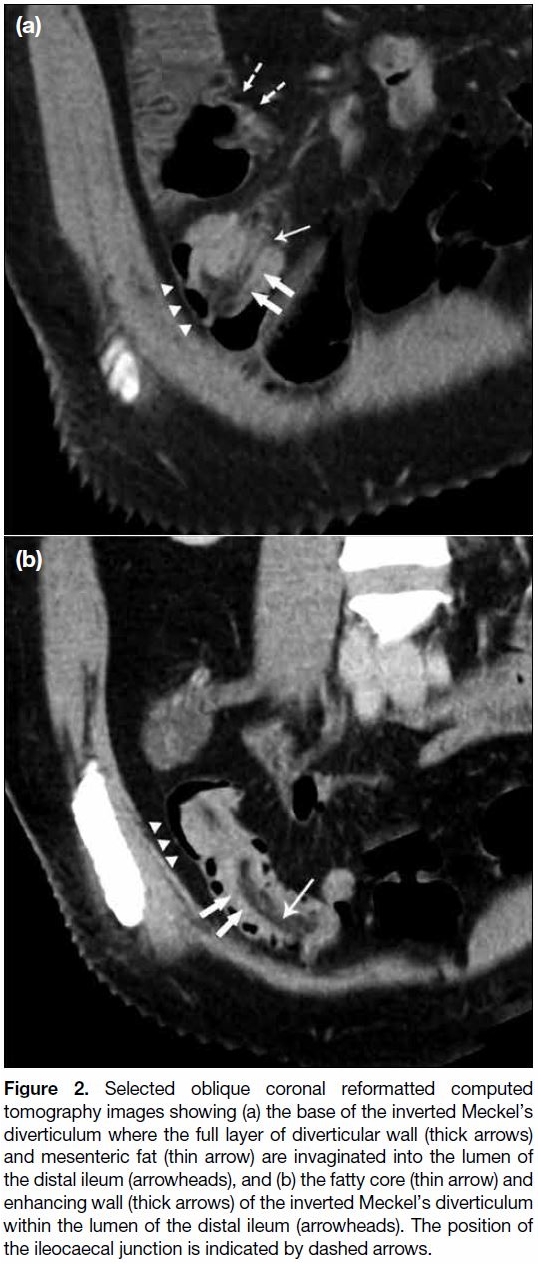

Computed tomographic angiography of the abdomen and

pelvis was arranged and revealed an elongated tubular

fat-containing lesion within the lumen of the distal ileum,

about 60 cm from the ileocaecal junction. The lesion

contained a central fatty core surrounded by a collar of

enhancing soft tissue (Figure 1). There was continuity

between mesenteric fat and the fatty core. Strand-like

densities were also observed within the fatty core and

appeared to be connected to branches of the mesenteric

vessels (Figure 2). No active contrast extravasation was

detected. Inverted Meckel’s diverticulum was the main

differential diagnosis given the morphology and location

of the lesion and its continuity with mesenteric fat.

Figure 1. Selected axial computed tomography images in the

angiographic phase showing the cross-sectional view of the

inverted Meckel’s diverticulum (a) at a higher position, its fatty core

(thin arrow); and (b) at a lower position, the enhancing wall (thick

arrow) of the inverted Meckel’s diverticulum, located within the

lumen of the distal ileum (arrowheads).

Figure 2. Selected oblique coronal reformatted computed

tomography images showing (a) the base of the inverted Meckel’s

diverticulum where the full layer of diverticular wall (thick arrows)

and mesenteric fat (thin arrow) are invaginated into the lumen of

the distal ileum (arrowheads), and (b) the fatty core (thin arrow) and

enhancing wall (thick arrows) of the inverted Meckel’s diverticulum

within the lumen of the distal ileum (arrowheads). The position of

the ileocaecal junction is indicated by dashed arrows.

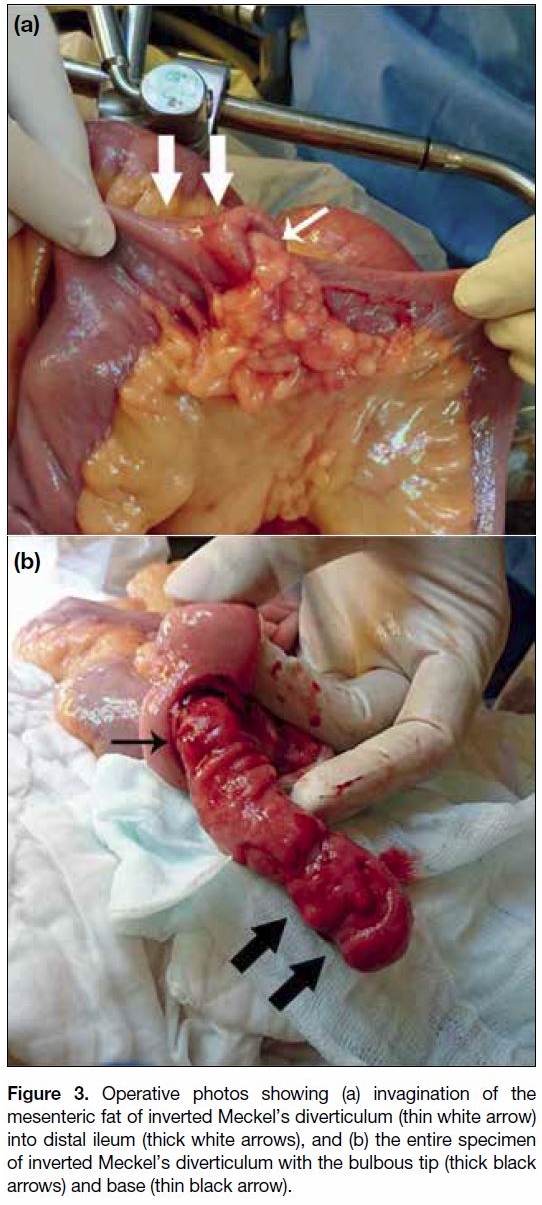

Urgent laparotomy was performed. Intraoperatively, a

mass was felt along the distal ileum, about two thirds

along the length of the small bowel from the ligament of Treitz. On the serosal side of the small bowel segment

where the mass was located, a focal point of invagination

of the bowel wall and mesenteric tissue into the luminal

side was identified. The finger-like intraluminal mass was

brought out via an enterostomy (Figure 3). Ulcerative

mucosa was seen along the inverted diverticular wall

with a pulsative spurter. The involved segment of small bowel was resected and an end-to-end ileoileal

anastomosis created. The procedure was uneventful.

Figure 3. Operative photos showing (a) invagination of the

mesenteric fat of inverted Meckel’s diverticulum (thin white arrow)

into distal ileum (thick white arrows), and (b) the entire specimen

of inverted Meckel’s diverticulum with the bulbous tip (thick black

arrows) and base (thin black arrow).

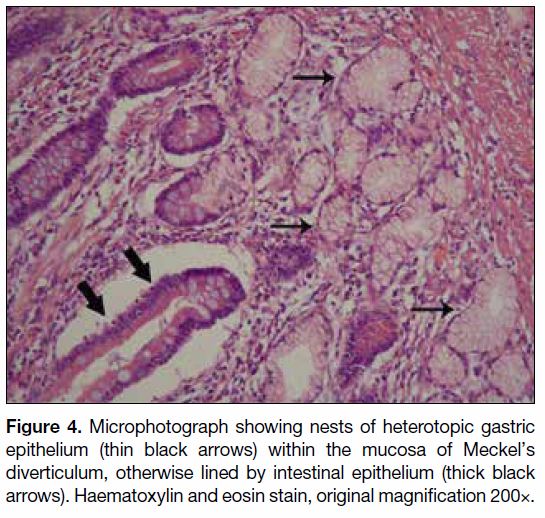

Gross examination of the resected specimen confirmed

an inverted diverticulum manifesting as a 7-cm long

tubular intraluminal mass. Histological examination

showed that the lesion contained all layers of the intestinal wall, as well as a core of fibroadipose tissue

that consisted of invaginated mesenteric tissue. The

mucosal surface of the lesion had focal ulcerations and

contained heterotopic gastric tissue (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Microphotograph showing nests of heterotopic gastric

epithelium (thin black arrows) within the mucosa of Meckel’s

diverticulum, otherwise lined by intestinal epithelium (thick black

arrows). Haematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification 200×.

DISCUSSION

Meckel’s diverticulum results from failure of regression

of the omphalomesenteric duct that connects the yolk sac to the mid gut through the umbilical cord in the

embryo. This duct typically closes by the 5th to 8th week

of gestation. Meckel’s diverticulum arises from the

antimesenteric border of the distal ileum, typically within

100 cm of the ileocaecal valve. It usually measures up to

5 cm in length and 2 cm in diameter. Heterotopic mucosa,

most commonly gastric type (up to 60%), is found

in about half of Meckel’s diverticula. Although most

Meckel’s diverticula remain clinically asymptomatic,

they can be complicated by haemorrhage from peptic

ulceration, diverticulitis, intussusception, volvulus, or

development of neoplasm within the diverticulum and

inversion.[1]

Inversion of Meckel’s diverticulum is a rare phenomenon,

with about 70 cases reported in the English literature.[2,3] The condition occurs when the diverticulum inverts

upon itself and invaginates into the lumen of the terminal

ileum. The pathophysiology is not well understood. One

theory is that abnormal peristaltic movement at the base

of the diverticulum due to ectopic tissue or ulceration

causes the diverticulum to invert.[4] The most common

complications are intussusception, where the inverted

diverticulum acts as a lead point, and gastrointestinal

bleeding due to ulceration in the inverted diverticulum.

Although ulceration in Meckel’s diverticulum is most

commonly due to acid secretion by heterotopic gastric

mucosa, it also occurs in inverted Meckel’s diverticulum

that does not contain heterotopic gastric mucosa. This is

postulated to be due to repeated mucosal trauma due to

intermittent intussusception of the diverticulum and its potential ischaemic vulnerability as the diverticulum is

supplied by the remnant of the vitelline artery, an end

branch of the superior mesenteric artery, and has no

collateral arterial supply.[4,5]

Patients with an inverted Meckel’s diverticulum can

present with a constellation of symptoms consistent

with acute or chronic gastrointestinal bleeding, intestinal

obstruction or recurrent abdominal pain, depending on

the complications.[3] Computed tomography (CT) is an

important diagnostic tool since clinical diagnosis of

inverted Meckel’s diverticulum can often be challenging.

Inverted Meckel’s diverticulum has characteristic

imaging features on CT. The inverted diverticulum

appears as a tubular intraluminal small bowel lesion

located in the distal small bowel with a central fatty core that demonstrates continuity with mesenteric fat. This

correlates with the invagination of mesenteric tissue

into the core of the inverted diverticulum. A thick rim of

enhancing soft tissue around the fatty core corresponds

to the full layer of the diverticular wall.[2,3,4] Intermittent

bleeding may cause false negative findings on CT

angiography.[6] Bowel-in-bowel appearance can be seen if

the diverticulum acts as the lead point for intussusception.[7]

These features readily allow differentiation from other

fat-containing small bowel lesions, namely lipoma and

ileal-ileal intussusception. A small bowel lipoma is

covered only by a thin layer of mucosa and lacks the thick

soft tissue collar seen in inverted Meckel’s diverticulum

(Figure 5). More importantly, the fat within the lipoma

does not demonstrate continuation with mesenteric

fat. In ileal-ileal intussusception, the central part of the

intussusceptum contains bowel lumen instead of fat and

the mesenteric fat lies between the intussusceptum and

intussuscipiens.

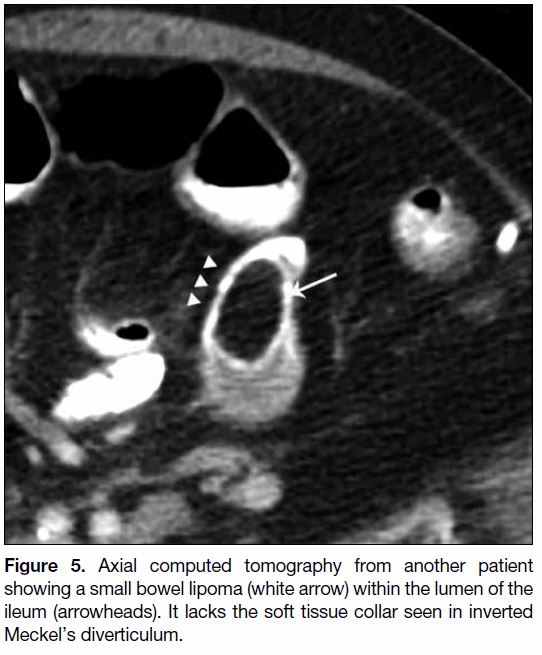

Figure 5. Axial computed tomography from another patient

showing a small bowel lipoma (white arrow) within the lumen of the

ileum (arrowheads). It lacks the soft tissue collar seen in inverted

Meckel’s diverticulum.

Definitive treatment of an inverted Meckel’s diverticulum

is surgical resection of the involved segment of small

bowel with subsequent anastomosis.[2]

REFERENCES

1. Levy AD, Hobbs CM. From the archives of the AFIP: Meckel

diverticulum: radiologic features with pathologic correlation.

Radiographics. 2004;24:565-87. Crossref

2. Pantongrag-Brown L, Levine MS, Elsayed AM, Buetow PC,

Agrons GA, Buck JL. Inverted Meckel diverticulum: clinical,

radiologic, and pathologic findings. Radiology. 1996:199;693-6. Crossref

3. Rashid OM, Ku JK, Nagahashi M, Yamada A, Takabe K. Inverted

Meckel’s diverticulum as a cause of occult lower gastrointestinal

hemorrhage. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6155-9. Crossref

4. Blakeborough A, McWilliams RG, Raja U, Robinson PJ,

Reynolds JV, Chapman AH. Pseudolipoma of inverted Meckel’s

diverticulum: clinical, radiological and pathological correlation. Eur

Radiol. 1997;7:900-4. Crossref

5. Heider R, Warshauer DM, Behrns KE. Inverted Meckel’s

diverticulum as a source of chronic gastrointestinal blood loss.

Surgery. 2000;128:107-8. Crossref

6. Artigas JM, Martí M, Soto JA, Esteban H, Pinilla I, Guillén E. Multidetector CT angiography for acute gastrointestinal bleeding:

technique and findings. Radiographics. 2013;33:1453-70. Crossref

7. Kim JH, Park SH, Ha HK. Case 156: Inverted Meckel diverticulum. Radiology. 2010;255:303-6. Crossref