Complications after Surgical Correction of Anorectal Malformations

CATELOG

Complications after Surgical Correction of Anorectal Malformations

T Hosokawa1, Y Yamada2, Y Tanami1, Y Sato1, Y Tanaka3, H Kawashima4, E Oguma1

1 Department of Radiology, Saitama Children’s Medical Center, Saitama, Japan

2 Department of Radiology, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan

3 Department of Pediatric Surgery, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Saitama, Japan

4 Department of Surgery, Saitama Children’s Medical Center, Saitama, Japan

Correspondence: Dr Takahiro Hosokawa, Department of Radiology, Saitama Children’s Medical Center, Saitama, Japan. Email: snowglobe@infoseek.jp

Submitted: 5 Nov 2018; Accepted: 3 Dec 2018.

Contributors: TH, YY and YTanami contributed to the design of the study. YTanami, YS and YTanaka acquired the data. TH, YY, YTanami,

YS and EO performed analysis or interpretation of data. TH and YY wrote the article. HK and EO carried out critical revision for important

intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Approval: This study is in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of our

institution. Informed consent was waived.

Abstract

Radiologists are often unfamiliar with anorectal malformations and have limited knowledge of the surgical procedures

for their repair. In this article, we provide a comprehensible description of the surgical procedures for radiologists,

review previous literature, and summarise the incidence of the complications. Moreover, we detail major postoperative

complications consequent to the use of various imaging techniques, including anorectal prolapse, anal stenosis,

urethral injury, posterior urethral diverticulum, neurogenic bladder, adhesion of reconstructed vagina, leakage

from suture lines, and trocar site hernia. Knowledge of these complications and surgical procedures is important to

radiologists for diagnosis and determination of a treatment strategy.

Key Words: Anorectal malformations; Anus, imperforate

中文摘要

肛門直腸畸形矯正術後的併發症

T Hosokawa、Y Yamada、Y Tanami、Y Sato、Y Tanaka、H Kawashima、E Oguma

放射科醫師通常不熟悉肛門直腸畸形,並且對其修復的手術程序認識有限。本文為放射科醫生提供

全面的手術方法說明、回顧文獻並總結併發症的發生率。此外,我們詳細介紹由於使用各種成像技

術顯示主要術後併發症,包括肛門直腸脫垂、肛門狹窄、尿道損傷、後尿道憩室、神經源性膀胱、

重建陰道粘連、縫合線滲漏以及套管針疝。這些併發症和手術程序的知識對於放射科醫生診斷和確

定治療策略很重要。

INTRODUCTION

Congenital anorectal malformations (ARMs), also

known as imperforate anus, affect approximately 1 in

5000 newborns.[1] These ARMs are classified as low,

intermediate, or high types,1 with treatment based on

this classification.[2] Although a variety of treatments

are available for imperforate anus, almost all cases of

low-type imperforate anus are managed with a one-step

anoplasty immediately after birth.[2] [3] In contrast, although

primary anorectal repair without a diverting enterostomy

is performed in some patients with intermediate- or

high-type imperforate anus,[3] [4] [5] almost all patients with

these types are treated first with a diverting colostomy,

then anorectoplasty.[3] [4] [5] Patients with ARMs are treated

with anorectoplasty for complete repair of the ARMs,

regardless of type. There are several other approaches

similar to anorectoplasty for complete surgical repair of

ARM.[4] [6] [7] [8] Currently, many surgical procedures, such as

perineal anorectoplasty, sacroperineal anorectoplasty,

abdominosacroperineal anorectoplasty, posterior

sagittal anorectoplasty (PSARP),[6] anterior sagittal

anorectoplasty (ASARP),[8] and laparoscopically assisted

anorectoplasty (LAARP)[4] are performed for complete

surgical repair of ARM. Despite advances in surgical

procedures, there are possibilities of postoperative

complications.

Reports on postoperative complications of surgical

repair of ARMs have documented the involvement

of pelvic organs (such as anus, rectum, urethra, and

vagina) as well as cutaneous structures.[9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28] Various

imaging techniques, such as plain radiography,

colonography, voiding cystourethrography,

ultrasonography, computed tomography, and

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used for

diagnosis.[9] [11] [16] [18] [19] [21] [29] [30] Unlike surgeons, radiologists

are often unfamiliar with ARMs and have little

knowledge about the surgical procedures for their

repair; to date, only one review article related to

radiography has been published.[30]

The aim of this article was to familiarise radiologists

with common complications of specific surgical

approaches and ARM types, which would be useful in

diagnosis and in assisting surgeons with the management

of these complications. In this article, we provide a

comprehensible description of the surgical procedures for

radiologists, review previous literature, and summarise

the incidence of complications. Moreover, we describe

and discuss eight major postoperative complications

specific to ARM, including anorectal prolapse, anal stenosis, urethral injury, posterior urethral diverticulum,

adhesion of reconstructed vagina, leakage from suture

lines, neurogenic bladder, and trocar site hernia.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Several surgical procedures are performed to repair

ARMs. Innovative approaches such as PSARP by Peña

and Devries[6] and LAARP by Georgeson et al[4] have been

reported. The anterior or posterior perineal approach is

selected according to fistula location and ARM type.

The anterior perineal approach is usually selected in low-type

or anovestibular ARM, and the posterior perineal

approach is usually selected for intermediate-type ARM

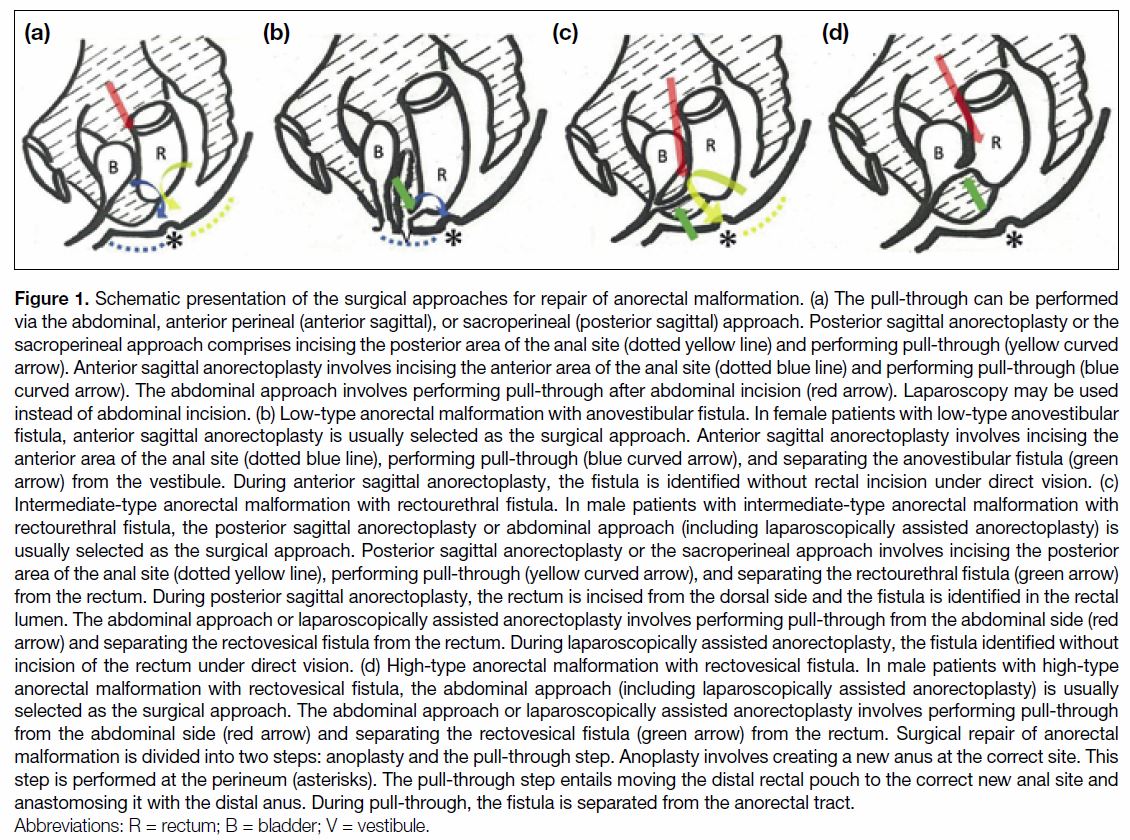

(Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic presentation of the surgical approaches for repair of anorectal malformation. (a) The pull-through can be performed

via the abdominal, anterior perineal (anterior sagittal), or sacroperineal (posterior sagittal) approach. Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty or the

sacroperineal approach comprises incising the posterior area of the anal site (dotted yellow line) and performing pull-through (yellow curved

arrow). Anterior sagittal anorectoplasty involves incising the anterior area of the anal site (dotted blue line) and performing pull-through (blue

curved arrow). The abdominal approach involves performing pull-through after abdominal incision (red arrow). Laparoscopy may be used

instead of abdominal incision. (b) Low-type anorectal malformation with anovestibular fistula. In female patients with low-type anovestibular

fistula, anterior sagittal anorectoplasty is usually selected as the surgical approach. Anterior sagittal anorectoplasty involves incising the

anterior area of the anal site (dotted blue line), performing pull-through (blue curved arrow), and separating the anovestibular fistula (green

arrow) from the vestibule. During anterior sagittal anorectoplasty, the fistula is identified without rectal incision under direct vision. (c)

Intermediate-type anorectal malformation with rectourethral fistula. In male patients with intermediate-type anorectal malformation with

rectourethral fistula, the posterior sagittal anorectoplasty or abdominal approach (including laparoscopically assisted anorectoplasty) is

usually selected as the surgical approach. Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty or the sacroperineal approach involves incising the posterior

area of the anal site (dotted yellow line), performing pull-through (yellow curved arrow), and separating the rectourethral fistula (green arrow)

from the rectum. During posterior sagittal anorectoplasty, the rectum is incised from the dorsal side and the fistula is identified in the rectal

lumen. The abdominal approach or laparoscopically assisted anorectoplasty involves performing pull-through from the abdominal side (red

arrow) and separating the rectovesical fistula from the rectum. During laparoscopically assisted anorectoplasty, the fistula identified without

incision of the rectum under direct vision. (d) High-type anorectal malformation with rectovesical fistula. In male patients with high-type

anorectal malformation with rectovesical fistula, the abdominal approach (including laparoscopically assisted anorectoplasty) is usually

selected as the surgical approach. The abdominal approach or laparoscopically assisted anorectoplasty involves performing pull-through

from the abdominal side (red arrow) and separating the rectovesical fistula (green arrow) from the rectum. Surgical repair of anorectal

malformation is divided into two steps: anoplasty and the pull-through step. Anoplasty involves creating a new anus at the correct site. This

step is performed at the perineum (asterisks). The pull-through step entails moving the distal rectal pouch to the correct new anal site and

anastomosing it with the distal anus. During pull-through, the fistula is separated from the anorectal tract.

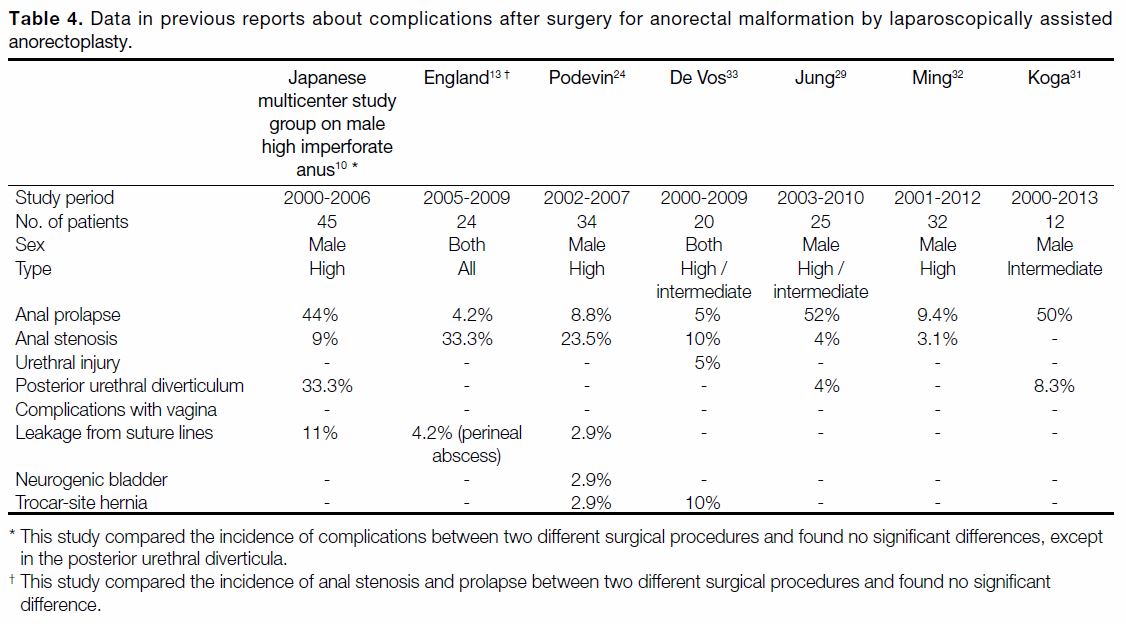

INCIDENCE AND DESCRIPTION OF

COMPLICATIONS

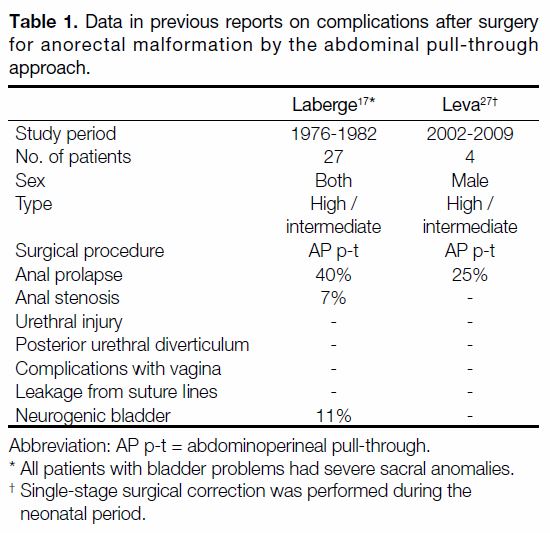

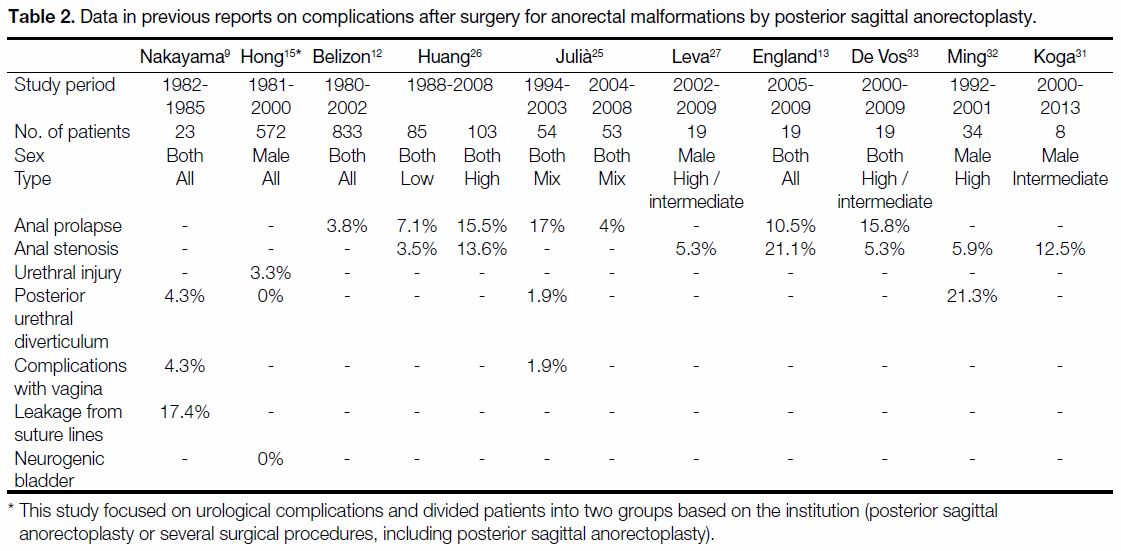

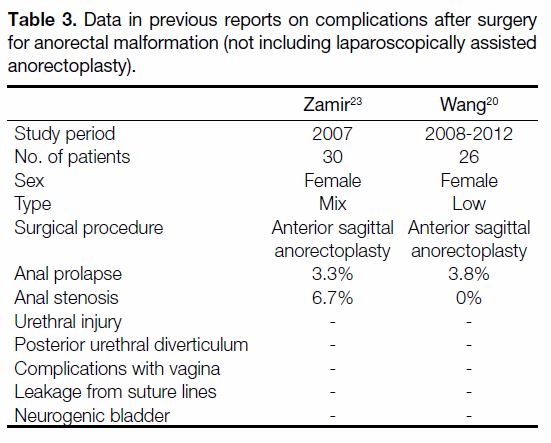

There are several approaches for surgical repair of ARMs,

and there are numerous reports on related complications.

We reviewed previous reports on complications after

surgery for ARM by the abdominal pull-through

approach (Table 1 [17] [27]), PSARP (Table 2 [9] [12] [13] [15] [25] [26] [27] [31] [32] [33]),

anterior sagittal anorectoplasty (Table 3 [20] [23]), and LAARP

(Table 4 [10] [13] [24] [29] [31] [32] [33]). Previous reports that included

multiple surgical approaches are excluded. The reports

exhibit differences with respect to patient sex and ARM

type. Therefore, the prevalence of each complication

shows variations. Furthermore, while the incidence of

the complications decreases with the improvement in

surgical techniques and skills,[10] [15] [25] some complications

still occur when the techniques are applied by highly

skilled surgeons.

Table 1. Data in previous reports on complications after surgery

for anorectal malformation by the abdominal pull-through

approach.

Table 2. Data in previous reports on complications after surgery for anorectal malformations by posterior sagittal anorectoplasty.

Table 3. Data in previous reports on complications after surgery

for anorectal malformation (not including laparoscopically assisted

anorectoplasty).

Table 4. Data in previous reports about complications after surgery for anorectal malformation by laparoscopically assisted

anorectoplasty.

Anal Prolapse

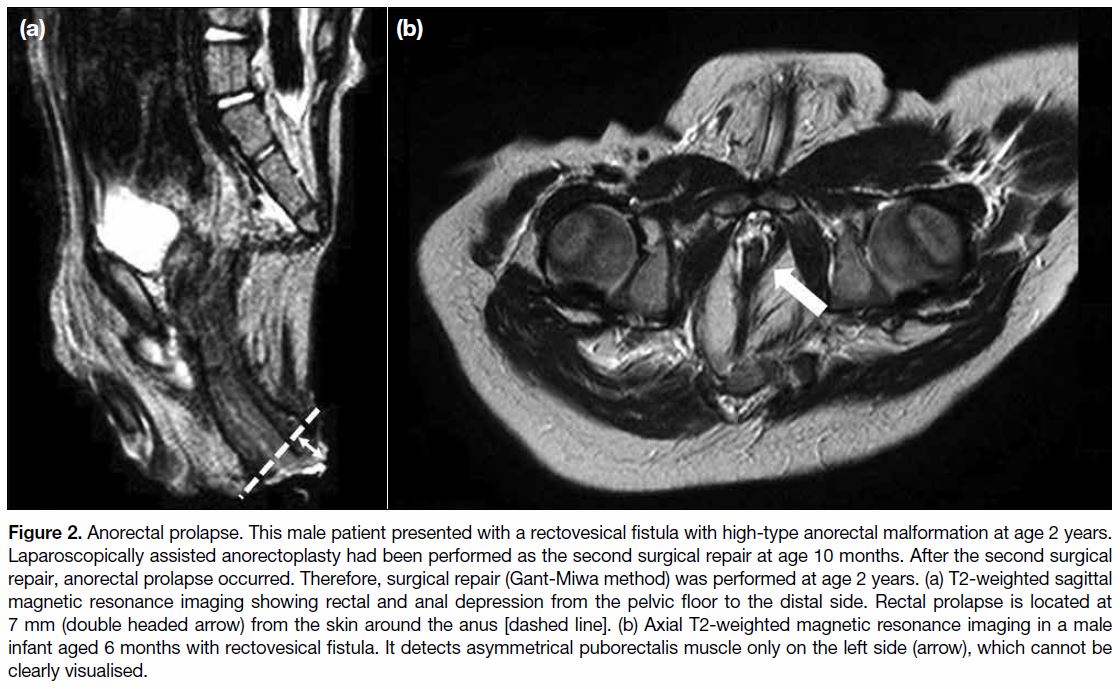

Anorectal prolapse (Figure 2) is defined as anal prolapse

>5 mm.[12] There have been no radiographic reports on

anorectal prolapse, as this complication is clinically

diagnosed. Anal prolapse has a significantly higher

incidence in patients with a low quality of the levator

ani muscle and in those with vertebral anomalies,[12] [22] and

the frequency of this complication is also reported to be

associated with surgical approaches as LAARP.[29] [31] [32] [34]

High-type ARM is characterised by poor muscle

quality, which may render anal prolapse an inevitable

complication, with a higher likelihood of recurrence than in low-type ARM.[26] [35] It may be accidentally detected on

an MRI requested to evaluate the levator ani muscle.[31] [36]

Figure 2. Anorectal prolapse. This male patient presented with a rectovesical fistula with high-type anorectal malformation at age 2 years.

Laparoscopically assisted anorectoplasty had been performed as the second surgical repair at age 10 months. After the second surgical

repair, anorectal prolapse occurred. Therefore, surgical repair (Gant-Miwa method) was performed at age 2 years. (a) T2-weighted sagittal

magnetic resonance imaging showing rectal and anal depression from the pelvic floor to the distal side. Rectal prolapse is located at

7 mm (double headed arrow) from the skin around the anus [dashed line]. (b) Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in a male

infant aged 6 months with rectovesical fistula. It detects asymmetrical puborectalis muscle only on the left side (arrow), which cannot be

clearly visualised.

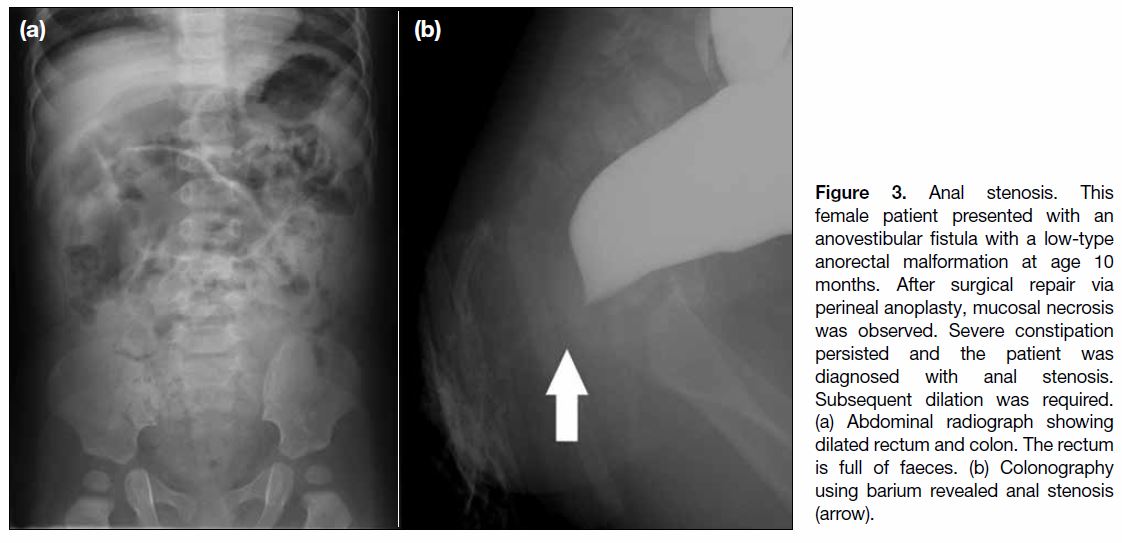

Anal Stenosis

Anal stenosis (Figure 3) may occur with all surgical

procedures and ARM types, and it may be caused by

ischaemia or inadequate dilation of the anus.[7] Ischaemic

necrosis of the pull-through bowel is a technical problem

caused by a reduction in vascular supply to the border

after colon mobilisation.[17] In abdominal radiography

after surgical repair of ARM, constipation rather than

poor levator ani muscle function may be observed, but

anal stenosis must still be considered.[36] [37]

Figure 3. Anal stenosis. This

female patient presented with an

anovestibular fistula with a low-type

anorectal malformation at age 10

months. After surgical repair via

perineal anoplasty, mucosal necrosis

was observed. Severe constipation

persisted and the patient was

diagnosed with anal stenosis.

Subsequent dilation was required.

(a) Abdominal radiograph showing

dilated rectum and colon. The rectum

is full of faeces. (b) Colonography

using barium revealed anal stenosis

(arrow).

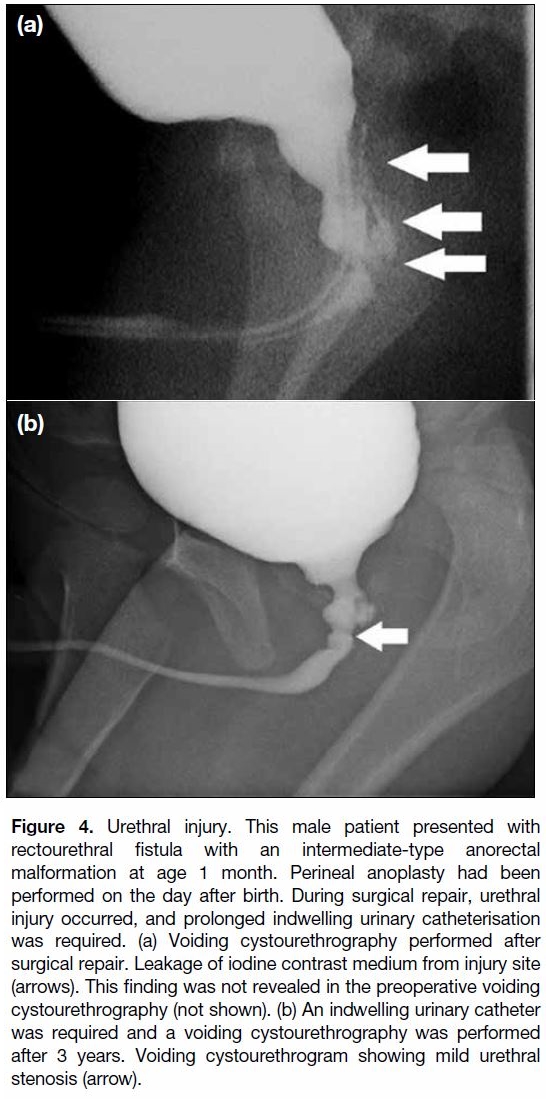

Urethral Injury

Urethral injury (Figure 4) during surgery has been found

to occur more often in male patients with intermediate- or

high-type ARM.[15] [38] To repair a rectourethral fistula,

separation of the urinary tract from the rectum is required.

Therefore, there is a risk of urethral injury while repairing

such an ARM, which should be avoided by paediatric

surgeons.[16] [19] To prevent injury to the urinary tract, an

augmented-pressure distal colostogram before surgical

repair is recommended.[15] [38]

Figure 4. Urethral injury. This male patient presented with

rectourethral fistula with an intermediate-type anorectal

malformation at age 1 month. Perineal anoplasty had been

performed on the day after birth. During surgical repair, urethral

injury occurred, and prolonged indwelling urinary catheterisation

was required. (a) Voiding cystourethrography performed after

surgical repair. Leakage of iodine contrast medium from injury site

(arrows). This finding was not revealed in the preoperative voiding

cystourethrography (not shown). (b) An indwelling urinary catheter

was required and a voiding cystourethrography was performed

after 3 years. Voiding cystourethrogram showing mild urethral

stenosis (arrow).

Urethral Injury

Urethral injury (Figure 4) during surgery has been found

to occur more often in male patients with intermediateor

high-type ARM.[15] [38] To repair a rectourethral fistula,

separation of the urinary tract from the rectum is required.

Therefore, there is a risk of urethral injury while repairing

such an ARM, which should be avoided by paediatric

surgeons.[16] [19] To prevent injury to the urinary tract, an

augmented-pressure distal colostogram before surgical

repair is recommended.[15] [38]

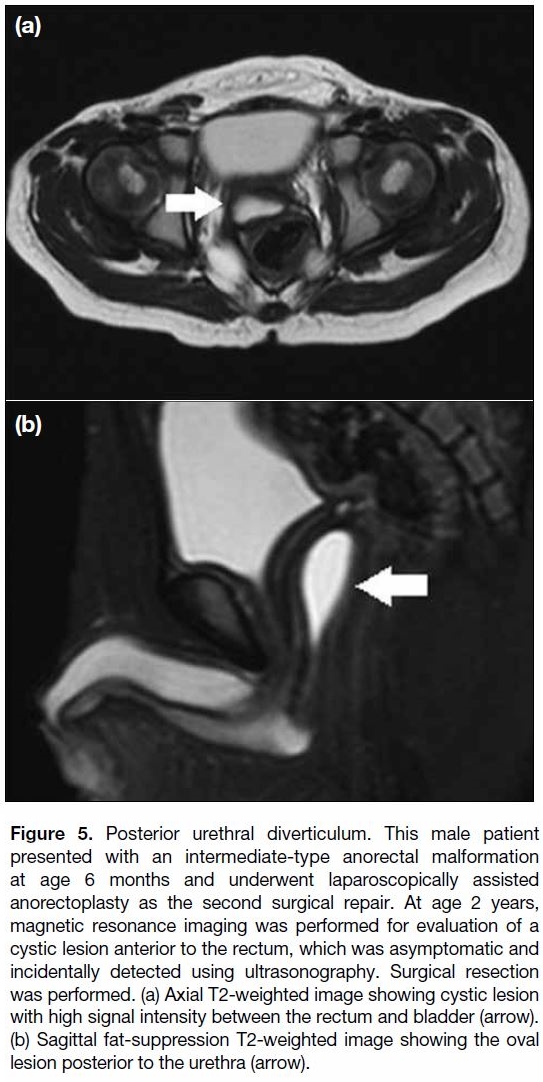

Posterior Urethral Diverticulum

Posterior urethral diverticulum (Figure 5) is more

likely to occur in LAARP than in the other types of

surgery.[10] This is important because it may result in dysuria, formation of urinary stones, infection, and

malignancy.[10] [16] [18] [19] Meanwhile, some patients with

posterior urethral diverticula may not exhibit any

symptoms.[10] [16] [18] [19] Therefore, it may be accidentally

detected on an MRI performed to evaluate the levator ani

muscle.[31] [36] There have been some radiographic reports about posterior urethral diverticulum, and in some cases,

posterior urethral diverticula could not be revealed using

voiding cystourethrography, being detectable only using

MRI.[10] [11] [16] [18] Histopathology of the excised mucosa of

the cyst showed colonic mucosa and confirmed that cyst

was indeed an enlarged residual rectourethral fistula.[16] To prevent posterior urethral diverticula, novel surgical

approaches and enhanced surgical skills are required.[16] [19] [39]

Figure 5. Posterior urethral diverticulum. This male patient

presented with an intermediate-type anorectal malformation

at age 6 months and underwent laparoscopically assisted

anorectoplasty as the second surgical repair. At age 2 years,

magnetic resonance imaging was performed for evaluation of a

cystic lesion anterior to the rectum, which was asymptomatic and

incidentally detected using ultrasonography. Surgical resection

was performed. (a) Axial T2-weighted image showing cystic lesion

with high signal intensity between the rectum and bladder (arrow).

(b) Sagittal fat-suppression T2-weighted image showing the oval

lesion posterior to the urethra (arrow).

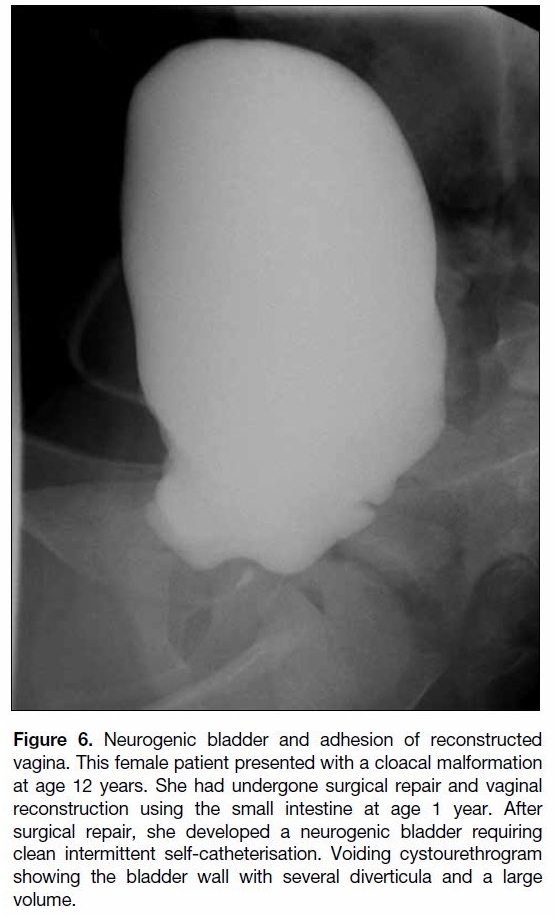

Neurogenic Bladder

Although neurogenic bladder (Figure 6) is a

complication of ARM repair,[15] [21] spinal anomalies

commonly accompany ARMs.[35] Laberge et al[17] reported

that three patients had prolonged poor bladder emptying

and that these patients had severe sacral anomalies.

However, determining whether the cause of neurogenic

bladder is iatrogenic may be difficult. Follow-up

regarding urological complications is important for management of patients with ARM.[40]

Figure 6. Neurogenic bladder and adhesion of reconstructed

vagina. This female patient presented with a cloacal malformation

at age 12 years. She had undergone surgical repair and vaginal

reconstruction using the small intestine at age 1 year. After

surgical repair, she developed a neurogenic bladder requiring

clean intermittent self-catheterisation. Voiding cystourethrogram

showing the bladder wall with several diverticula and a large

volume.

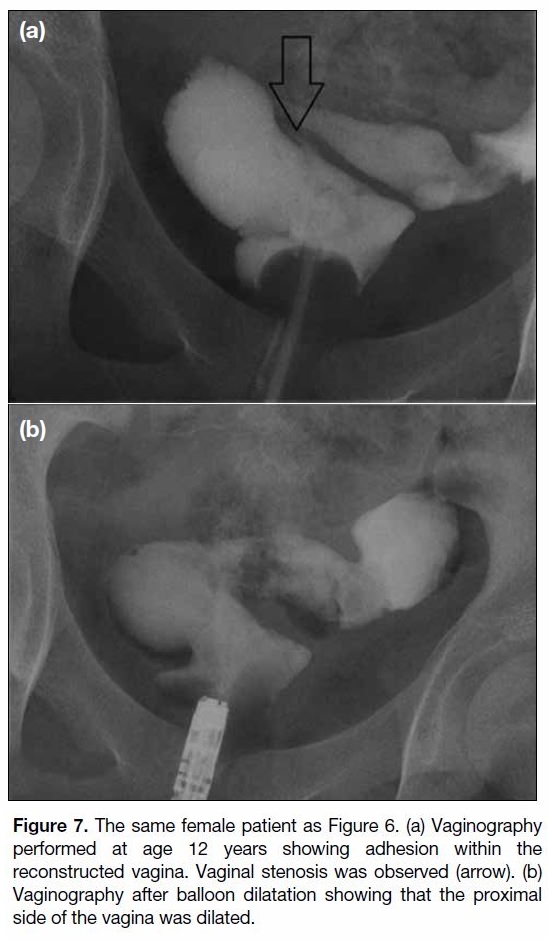

Adhesion of Reconstructed Vagina

Reconstruction of the vagina may be required in girls

with cloacal malformation, which is classified as high-type

ARM. Reconstruction of the vagina using the

intestine has been previously reported,[41] with some

patients requiring dilatation.[41] Partial adhesion (Figure 7)

of the reconstructed vagina or uterus must be diagnosed

early to reduce decline in quality of life of patients

with ARMs.[41] Furthermore, some patients may require

additional surgical repair.[42] [43] [44] [45]

Figure 7. The same female patient as Figure 6. (a) Vaginography

performed at age 12 years showing adhesion within the

reconstructed vagina. Vaginal stenosis was observed (arrow). (b)

Vaginography after balloon dilatation showing that the proximal

side of the vagina was dilated.

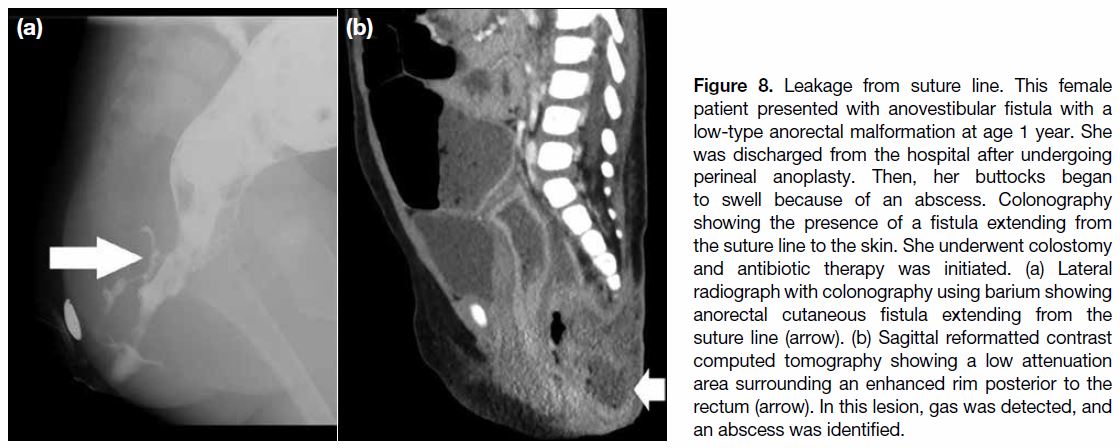

Leakage from Suture Lines

Leakage from suture lines (Figure 8), failed

anastomoses, and perineal abscesses has been

reported.[9] [10] [13] [14] Infection after operation is a common

complication,[9] [10] [13] [14] [20] and the diagnosis of leakage

from the suture line is important in determining the

best treatment option. Leaks may be detected with

colonography,[9] whereas only one report has included

radiographic images.[9] Fistula repair can be achieved via

colonostomy, antibiotic therapy, and spontaneous selfclosure.

[9] [13] [14]

Figure 8. Leakage from suture line. This female

patient presented with anovestibular fistula with a

low-type anorectal malformation at age 1 year. She

was discharged from the hospital after undergoing

perineal anoplasty. Then, her buttocks began

to swell because of an abscess. Colonography

showing the presence of a fistula extending from

the suture line to the skin. She underwent colostomy

and antibiotic therapy was initiated. (a) Lateral

radiograph with colonography using barium showing

anorectal cutaneous fistula extending from the

suture line (arrow). (b) Sagittal reformatted contrast

computed tomography showing a low attenuation

area surrounding an enhanced rim posterior to the

rectum (arrow). In this lesion, gas was detected, and

an abscess was identified.

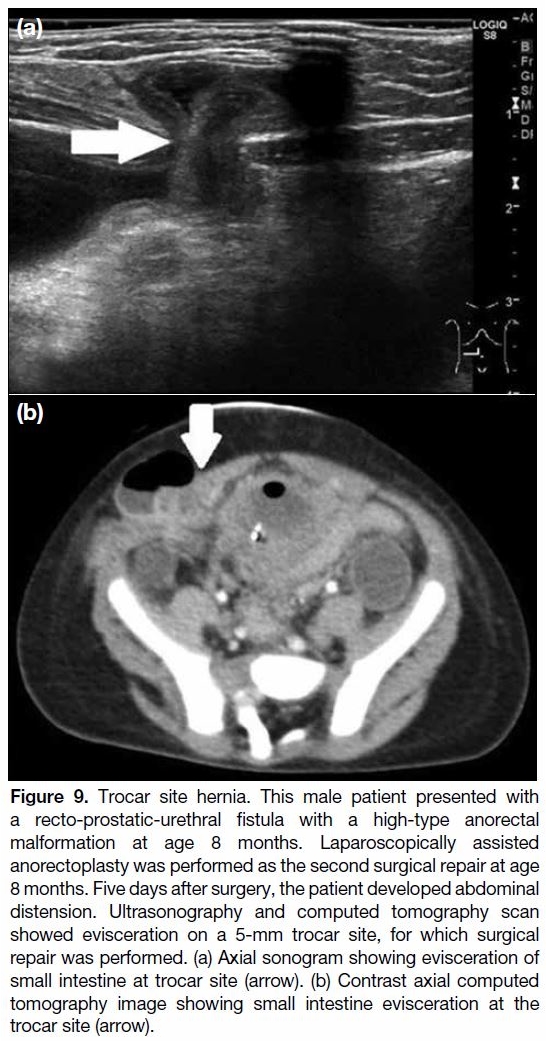

Trocar Site Hernia

LAARP is associated with trocar site hernia (Figure 9).

Previous studies have shown that the incidence of this

complication ranges between 1% and 10%.[24] [33] [46] [47] More than 90% of trocar site hernias are within 10 mm,[46] [47]

and they have occurred in paediatric patients.[24] [33] Some

cases may need surgical repair because of small bowel

obstruction with strangulation caused by a port site

hernia.[48] If this complication is detected, radiologists

should evaluate the possibility of bowel strangulation.

To prevent this complication, laparoscopic port closure

is usually performed using different techniques.[49] [50] For

radiologists, knowledge of trocar site hernia is important

for early diagnosis.

Figure 9. Trocar site hernia. This male patient presented with

a recto-prostatic-urethral fistula with a high-type anorectal

malformation at age 8 months. Laparoscopically assisted

anorectoplasty was performed as the second surgical repair at age

8 months. Five days after surgery, the patient developed abdominal

distension. Ultrasonography and computed tomography scan

showed evisceration on a 5-mm trocar site, for which surgical

repair was performed. (a) Axial sonogram showing evisceration of

small intestine at trocar site (arrow). (b) Contrast axial computed

tomography image showing small intestine evisceration at the

trocar site (arrow).

CONCLUSION

We have described eight complications after surgery for

ARM. These complications involve the pelvic organs.

Various imaging techniques are used to diagnose these

complications. Although the incidence of these types of complications varies across reports, knowledge

of their manifestation and treatment is important for

radiologists.

REFERENCES

1. Santulli, TV, Kiesewetter WB, Bill AH Jr. Anorectal anomalies: a

suggested international classification. J Pediatr Surg. 1970;5:281-7. Crossref

2. Peña A. Management of anorectal malformations during the

newborn period. World J Surg. 1993;17:385-92. Crossref

3. Morandi A, Ure B, Leva E, Lacher M. Survey on the management

of anorectal malformations (ARM) in European pediatric surgical

centers of excellence. Pediatr Surg Int. 2015;31:543-50. Crossref

4. Georgeson KE, Inge TH, Albanese CT. Laparoscopically assisted

anorectal pull-through for high imperforate anus — a new

technique. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:927-30. Crossref

5. Vick LR, Gosche JR, Boulanger SC, Islam S. Primary laparoscopic

repair of high imperforate anus in neonatal males. J Pediatr Surg.

2007;42:1877-81. Crossref

6. Peña A, Devries PA. Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty: important

technical considerations and new applications. J Pediatr Surg.

1982;17:796-811. Crossref

7. Peña A. Atlas of Surgical Management of Anorectal Malformations.

New York (NY): Springer; 1989.

8. Okada A, Kamata S, Imura K, Fukuzawa M, Kubota A, Yagi

M, et al. Anterior sagittal anorectoplasty for rectovestibular and

anovestibular fistula. J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:85-8. Crossref

9. Nakayama DK, Templeton JM Jr, Ziegler MM, O’Neill JA, Walker

AB. Complications of posterior sagittal anorectoplasty. J Pediatr

Surg. 1986;21:488-92. Crossref

10. Japanese multicenter study group on male high imperforate anus.

Multicenter retrospective comparative study of laparoscopically

assisted and conventional anorectoplasty for male infants with

rectoprostatic urethral fistula. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:2383-8. Crossref

11. Alam S, Lawal TA, Peña A, Sheldon C, Levitt MA. Acquired

posterior urethral diverticulum following surgery for anorectal

malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:1231-5. Crossref

12. Belizon A, Levitt M, Shoshany G, Rodriguez G, Peña A. Rectal

prolapse following posterior sagittal anorectoplasty for anorectal

malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:192-6. Crossref

13. England RJ, Warren SL, Bezuidenhout L, Numanoglu A, Millar AJ.

Laparoscopic repair of anorectal malformations at the Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital: taking stock. J Pediatr Surg.

2012;47:565-70. Crossref

14. Freeman NV, Bulut M. “High” anorectal anomalies treated by early

(neonatal) operation. J Pediatr Surg. 1986;21:218-20. Crossref

15. Hong AR, Acuña MF, Peña A, Chaves L, Rodriguez G. Urologic

injuries associated with repair of anorectal malformations in male

patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:339-44. Crossref

16. Koga H, Okazaki T, Yamataka A, Kobayashi H, Yanai T, Lane GJ, et al.

Posterior urethral diverticulum after laparoscopic-assisted repair

of high-type anorectal malformation in a male patient: surgical

treatment and prevention. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21:58-60. Crossref

17. Laberge JM, Bosc O, Yazbeck S, Youssef S, Ducharme JC,

Guttman FM, et al. The anterior perineal approach for pull-through

operations in high imperforate anus. J Pediatr Surg. 1983;18:774-8. Crossref

18. Podberesky DJ, Weaver NC, Anton CG, Lawal T, Hamrick MC,

Alam S, et al. MRI of acquired posterior urethral diverticulum

following surgery for anorectal malformations. Pediatr Radiol.

2011;41:1139-45. Crossref

19. Vinnicombe SJ, Good CD, Hall CM. Posterior urethral diverticula:

a complication of surgery for high anorectal malformations. Pediatr

Radiol. 1996;26:120-6. Crossref

20. Wang C, Li L, Liu S, Chen Z, Diao M, Li X, et al. The management

of anorectal malformation with congenital vestibular fistula: a

single-stage modified anterior sagittal anorectoplasty. Pediatr Surg

Int. 2015;31:809-14. Crossref

21. Williams DI, Grant J. Urological complications of imperforate

anus. Br J Urol. 1969;41:660-5. Crossref

22. Zornoza M, Molina E, Cerdá J, Fanjul M, Corona C, Tardáguila AR, et al.

Postoperative anal prolapse in patients with anorectal malformations:

16 years of experience [in Spanish]. Cir Pediatr. 2012;25:140-4.

23. Zamir N, Mirza FM, Akhtar J, Ahmed S. Anterior sagittal approach

for anorectal malformations in female children: early results. J Coll

Physicians Surg Pak. 2008;18:763-7.

24. Podevin G, Petit T, Mure PY, Gelas T, Demarche M, Allal H, et al.

Minimally invasive surgery for anorectal malformation in boys:

a multicenter study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19

Suppl 1:S233-5. Crossref

25. Julià V, Tarrado X, Prat J, Saura L, Montaner A, Castañón M,

et al. Fifteen years of experience in the treatment of anorectal

malformations. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010;26:145-9. Crossref

26. Huang CF, Lee HC, Yeung CY, Chan WT, Jiang CB, Sheu JC,

et al. Constipation is a major complication after posterior sagittal

anorectoplasty for anorectal malformations in children. Pediatr

Neonatol. 2012;53:252-6. Crossref

27. Leva E, Macchini F, Arnoldi R, Di Cesare A, Gentilino V,

Fumagalli M, et al. Single-stage surgical correction of anorectal

malformation associated with rectourinary fistula in male neonates.

J Neonatal Surg. 2013;2:3.

28. Ramasundaram M, Sundaram J, Agarwal P, Bagdi RK, Bharathi S,

Arora A. Institutional experience with laparoscopic-assisted

anorectal pull-through in a series of 17 cases: a retrospective

analysis. J Minim Access Surg. 2017;13:265-8. Crossref

29. Jung SM, Lee SK, Seo JM. Experience with laparoscopic-assisted

anorectal pull-through in 25 males with anorectal malformation and

rectourethral or rectovesical fistulae: postoperative complications

and functional results. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:591-6. Crossref

30. Eltomey MA, Donnelly LF, Emery KH, Levitt MA, Peña A.

Postoperative pelvic MRI of anorectal malformations. AJR Am J

Roentgenol. 2008;191:1469-76. Crossref

31. Koga H, Ochi T, Okawada M, Doi T, Lane GJ, Yamataka A.

Comparison of outcomes between laparoscopy-assisted and

posterior sagittal anorectoplasties for male imperforate anus with

recto-bulbar fistula. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:1815-7. Crossref

32. Ming AX, Li L, Diao M, Wang HB, Liu Y, Ye M, et al. Long term

outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted anorectoplasty: a comparison

study with posterior sagittal anorectoplasty. J Pediatr Surg.

2014;49:560-3. Crossref

33. De Vos C, Arnold M, Sidler D, Moore SW. A comparison of

laparoscopic-assisted (LAARP) and posterior sagittal (PSARP)

anorectoplasty in the outcome of intermediate and high anorectal

malformations. S Afr J Surg. 2011;49:39-43.

34. Yazaki Y, Koga H, Ochi T, Okawada M, Doi T, Lane GJ, et al.

Surgical management of recto-prostatic and recto-bulbar anorectal

malformations. Pediatr Surg Int. 2016;32:939-44. Crossref

35. Hosokawa T, Yamada Y, Tanami Y, Hattori S, Sato Y, Tanaka Y,

et al. Sonography for an imperforate anus: approach, timing of the

examination, and evaluation of the type of imperforate anus and

associated anomalies. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:1747-58. Crossref

36. Yong C, Ruo-yi W, Yuan Z, Shu-hui Z, Guang-Rui S. MRI findings

in patients with defecatory dysfunction after surgical correction of

anorectal malformation. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43:964-70. Crossref

37. Gangopadhyay AN, Pandey V, Gupta DK, Sharma SP, Kumar V,

Verma A. Assessment and comparison of fecal continence in

children following primary posterior sagittal anorectoplasty and

abdominoperineal pull through for anorectal anomaly using clinical

scoring and MRI. J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51:430-4. Crossref

38. Kraus SJ, Levitt MA, Peña A. Augmented-pressure distal

colostogram: the most important diagnostic tool for planning

definitive surgical repair of anorectal malformations in boys. Pediatr

Radiol. 2018;48:258-69. Crossref

39. Yamataka A, Lane GJ, Koga H. Laparoscopy-assisted surgery for

male imperforate anus with rectourethral fistula. Pediatr Surg Int.

2013;29:1007-11. Crossref

40. Ralph DJ, Woodhouse CR, Ransley PG. The management of the

neuropathic bladder in adolescents with imperforate anus. J Urol.

1992;148(2 Pt 1):366-8. Crossref

41. O’Connor JL, DeMarco RT, Pope JC 4th, Adams MC, Brock JW 3rd.

Bowel vaginoplasty in children: a retrospective review. J Pediatr

Surg. 2004;39:1205-8. Crossref

42. Kyrklund, K, Taskinen S, Rintala RJ, Pakarinen MP. Sexual

function, fertility and quality of life after modern treatment of

anorectal malformations. J Urol. 2016;196:1741-6. Crossref

43. Grano C, Bucci S, Aminoff D, Lucidi F, Violani C. Quality of life

in children and adolescents with anorectal malformation. Pediatr

Surg Int. 2013;29:925-30. Crossref

44. Skerritt C, Vilanova Sanchez A, Lane VA, Wood RJ, Hewitt GD,

Breech LL, et al. Menstrual, sexual, and obstetrical outcomes after

vaginal replacement for vaginal atresia associated with anorectal

malformation. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2017;27:495-502. Crossref

45. Vilanova-Sanchez A, Reck CA, McCracken KA, Lane VA, Gasior AC,

Wood RJ, et al. Gynecologic anatomic abnormalities following

anorectal malformations repair. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53:698-703. Crossref

46. Di Lorenzo N, Coscarella G, Lirosi F, Pietrantuono M, Susanna F,

Gaspari A. Trocars and hernias: a simple, cheap remedy [in Italian].

Chir Ital. 2005;57:87-90.

47. Hussain A, Mahmood H, Singhal T, Balakrishnan S, Nicholls J,

El-Hasani S. Long-term study of port-site incisional hernia after

laparoscopic procedures. JSLS. 2009;13:346-9.

48. Rammohan A, Naidu RM. Laparoscopic port site Richter’s hernia—an important lesson learnt. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2011;2:9-11. Crossref

49. Di Lorenzo N, Coscarella G, Lirosi F, Gaspari A. Port-site closure:

a new problem, an old device. JSLS. 2002;6:181-3.

50. Singal R, Zaman M, Mittal A, Singal S, Sandhu K, Mittal A.

No need of fascia closure to reduce trocar site hernia rate in

laparoscopic surgery: a prospective study of 200 non-obese patients.

Gastroenterology Res. 2016;9:70-3. Crossref