Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Recurrence with Orbital Metastasis through the Nasolacrimal Duct: Uncommon Presentation of a Common Phenomenon

CASE REPORT

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Recurrence with Orbital Metastasis through the Nasolacrimal Duct: Uncommon Presentation of

a Common Phenomenon

KTF Ng1, WH Luk1, WT Ngai2

1 Department of Radiology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

2 Department of Nuclear Medicine, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

Correspondence: Dr KTF Ng, Department of Radiology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong. Email: h0440257@gmail.com

Submitted: 5 Jun 2019; Accepted: 9 Aug 2019.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the concept and design of study, acquisition of data, interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript,

and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved

the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This case report received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Approval: The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Verbal consent was obtained from the patient.

INTRODUCTION

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is one of the

most common malignancies with the tenth highest

mortality of all malignancies in Hong Kong in 2016.[1]

Despite the emergence of more advanced treatments

such as intensity-modulated radiotherapy, tumour

recurrence is still encountered. The presentation of

NPC recurrence is known to be highly variable. We

report an uncommon presentation with metastasis

through the nasolacrimal duct detected on positron

emission tomography–computed tomography

(PET-CT).

HISTORY

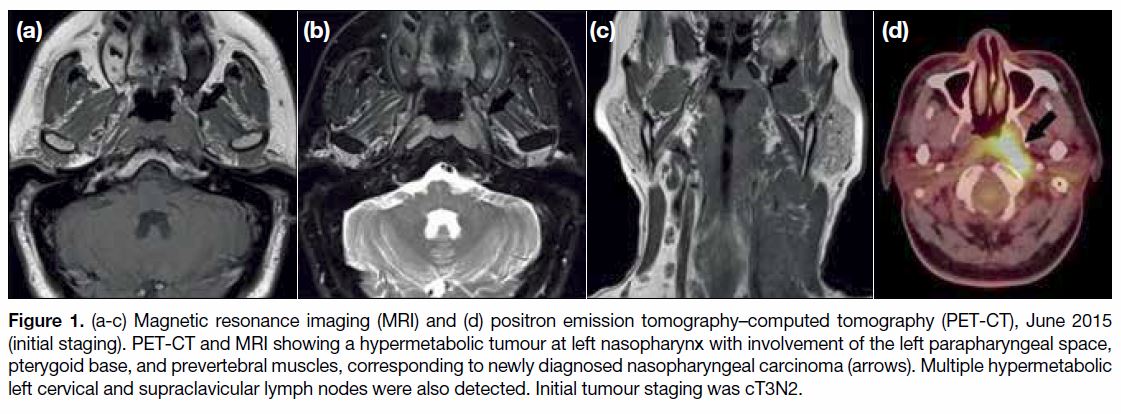

A 44-year-old man was diagnosed with undifferentiated

NPC in July 2015 (Figure 1). He first presented with

nasal obstruction, postnasal dripping with blood stained

saliva, and self-palpated neck mass for 2 months.

Nasoendoscopy revealed a left nasopharyngeal mass and

biopsy confirmed an undifferentiated NPC. Ultrasound

of the neck revealed multiple cervical lymph nodes.

PET-CT and magnetic resonance imaging scans showed

a corresponding hypermetabolic tumour at the left nasopharynx with involvement of the left parapharyngeal

space, pterygoid base, and prevertebral muscles. Multiple

hypermetabolic left cervical and supraclavicular lymph

nodes were also detected. Initial tumour staging was

cT3N2.

Figure 1. (a-c) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and (d) positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT), June 2015

(initial staging). PET-CT and MRI showing a hypermetabolic tumour at left nasopharynx with involvement of the left parapharyngeal space,

pterygoid base, and prevertebral muscles, corresponding to newly diagnosed nasopharyngeal carcinoma (arrows). Multiple hypermetabolic

left cervical and supraclavicular lymph nodes were also detected. Initial tumour staging was cT3N2.

The patient was commenced on chemoradiotherapy. A

total of six cycles of cisplatin and radiation therapy at a

dose of 61.48 Gy in 29 fractions were given. Subsequent

nasopharyngoscopy showed no residual tumour and

biopsy was negative for malignancy. Subsequent

adjuvant chemotherapy of three cycles of cisplatin-fluorouracil

was completed in December 2015.

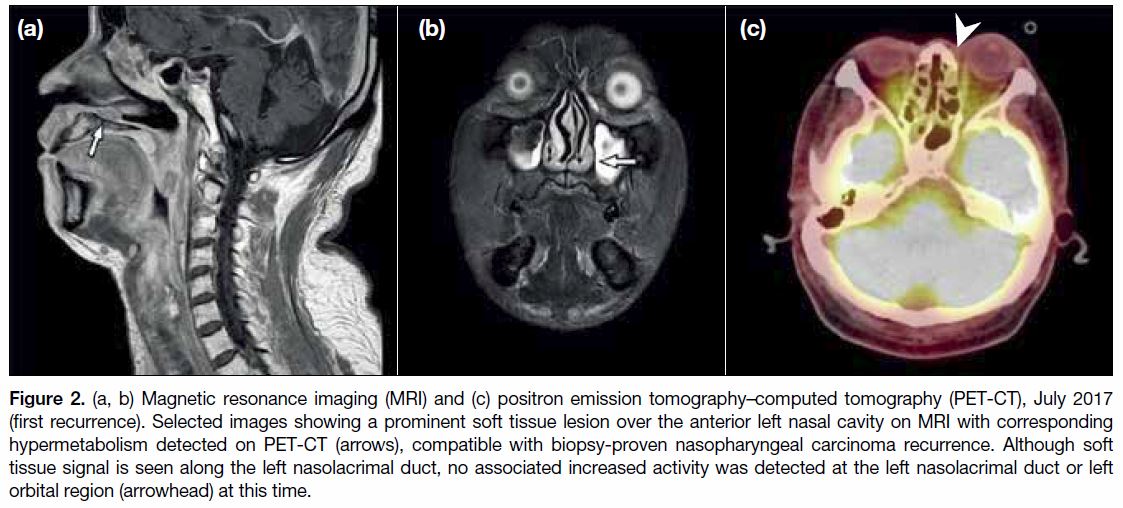

During a follow-up visit in July 2017, multiple enlarged

cervical lymph nodes were detected. Magnetic resonance

imaging and PET-CT scans of the neck and nasopharynx

in July 2017 (Figure 2) showed prominent soft tissue

lesions with hypermetabolism over the anterior nasal

cavity, left nasopharynx, left tonsil, and bilateral cervical

lymph nodes. Subsequent upper endoscopy detected

corresponding friable soft tissue masses in the left nasal

cavity, as well as a left nasopharyngeal mass involving the left roof, lateral wall, and left choana. Biopsy of both

masses confirmed recurrent undifferentiated NPC.

Figure 2. (a, b) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and (c) positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT), July 2017

(first recurrence). Selected images showing a prominent soft tissue lesion over the anterior left nasal cavity on MRI with corresponding

hypermetabolism detected on PET-CT (arrows), compatible with biopsy-proven nasopharyngeal carcinoma recurrence. Although soft

tissue signal is seen along the left nasolacrimal duct, no associated increased activity was detected at the left nasolacrimal duct or left

orbital region (arrowhead) at this time.

The patient declined surgery or repeat radiotherapy so

second-line chemotherapy was offered. A total of five

cycles of gemcitabine-cisplatin were given, switched

to gemcitabine-carboplatin for two more cycles due

to hearing loss. The patient showed an initial partial

response. Serologically, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA

titre in February 2018 had reduced to an undetectable

level from a pretreatment baseline of 765 copies/mL.

Follow-up CT in March 2018 showed a less conspicuous

soft tissue thickening at the left nasopharynx and

oropharynx with interval resolution of the nasal floor

soft tissue lesion. Bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy

also showed interval shrinkage.

However, the EBV DNA titre showed a rebound level of

52 copies/mL in November 2018, suspicious of disease

progression. The patient also complained of a new

1.5-cm firm mass at the left nasal bridge just medial to

the left orbit and enlarging over the last month. The

patient was referred to our centre for PET-CT to

determine disease progress.

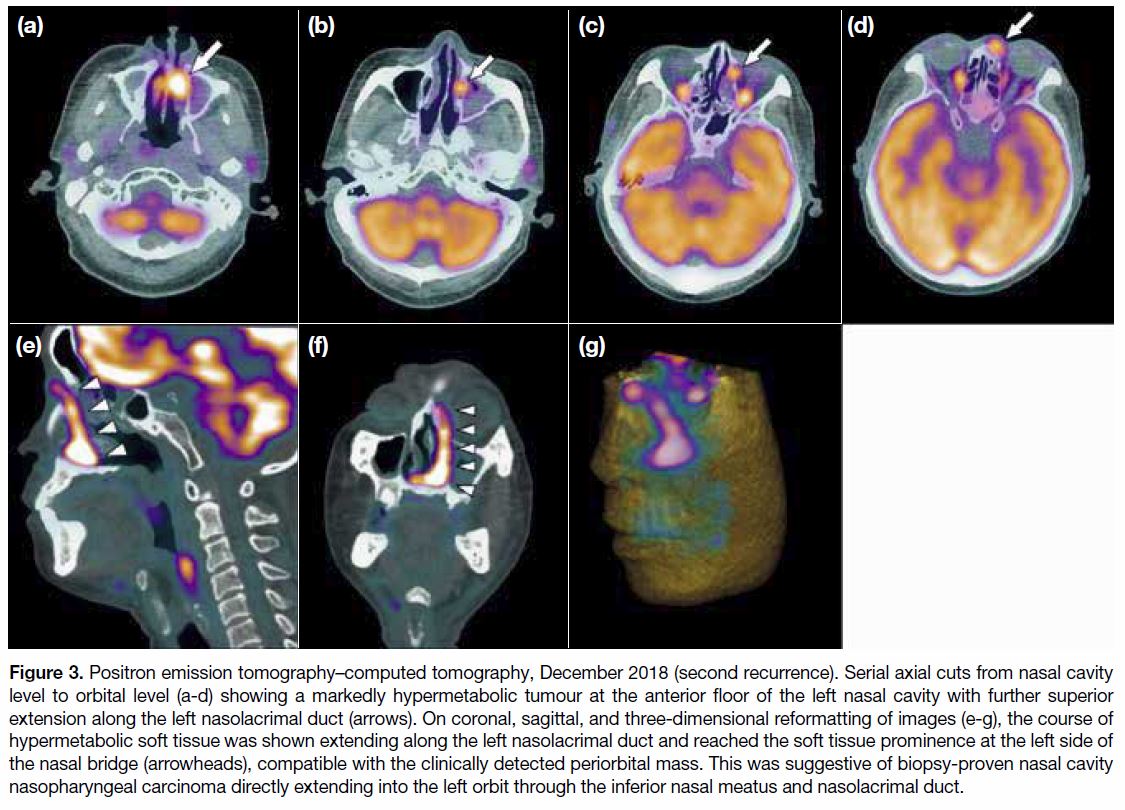

Follow-up PET-CT in December 2018 (Figure 3)

revealed a markedly hypermetabolic tumour centred at

the anterior floor of the left nasal cavity with involvement

of the nasal septum and right anterior nasal cavity. The

hypermetabolism showed further superior extension

along the left nasolacrimal duct that was mildly expanded

by soft tissue, and reached a soft tissue prominence at

the left side of the nasal bridge, compatible with the clinically detected periorbital mass. This was suggestive

of the biopsy-proven nasal cavity NPC showing direct

extension into the left orbit through the inferior nasal

meatus and nasolacrimal duct. Hypermetabolic nodal lesions were also noted at bilateral parotid, submental,

and upper cervical regions, likely representing nodal

recurrence. Overall imaging features were compatible

with disease progression.

Figure 3. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography, December 2018 (second recurrence). Serial axial cuts from nasal cavity

level to orbital level (a-d) showing a markedly hypermetabolic tumour at the anterior floor of the left nasal cavity with further superior

extension along the left nasolacrimal duct (arrows). On coronal, sagittal, and three-dimensional reformatting of images (e-g), the course of

hypermetabolic soft tissue was shown extending along the left nasolacrimal duct and reached the soft tissue prominence at the left side of

the nasal bridge (arrowheads), compatible with the clinically detected periorbital mass. This was suggestive of biopsy-proven nasal cavity

nasopharyngeal carcinoma directly extending into the left orbit through the inferior nasal meatus and nasolacrimal duct.

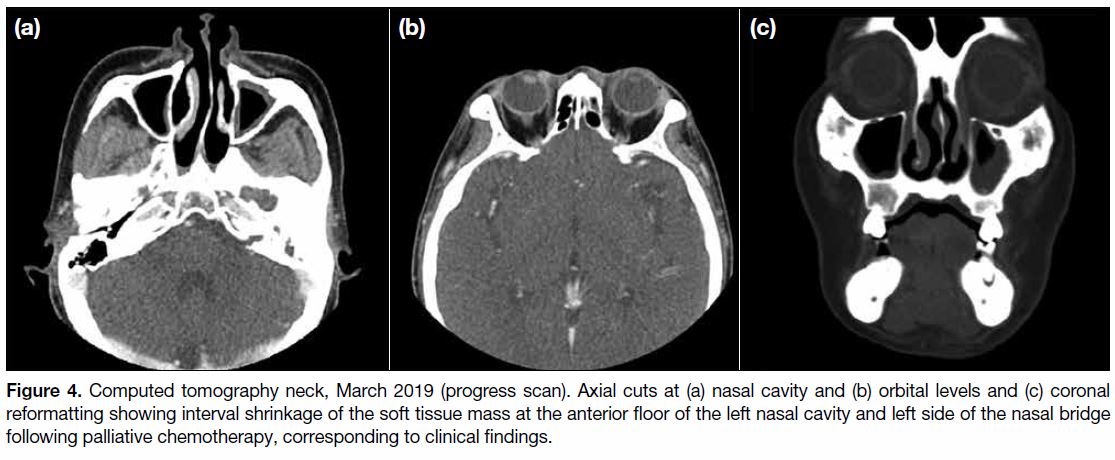

In view of disease progression, the patient was offered

palliative chemotherapy with capecitabine. The medial

orbital mass showed progressive flattening on subsequent

clinical follow-ups and showed interval resolution on

follow-up CT after 3 months (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Computed tomography neck, March 2019 (progress scan). Axial cuts at (a) nasal cavity and (b) orbital levels and (c) coronal

reformatting showing interval shrinkage of the soft tissue mass at the anterior floor of the left nasal cavity and left side of the nasal bridge

following palliative chemotherapy, corresponding to clinical findings.

DISCUSSION

Although skull base infiltration of NPC through the

neuroforamen or potential spaces is a well-known

phenomenon, orbital infiltration is uncommon. It has

been reported by Luo et al[2] and Colaco et al[3] that the most

common pathway for NPC infiltration into the orbit is

via the pterygopalatine fossa and inferior orbital fissure,

followed by via ethmoid sinus and sphenoid sinus,

reaching the orbital apex. Common orbital metastatic

tumours often present with a rather abrupt onset of

diplopia, blurred vision, pain, and occasionally a visible

lump. Examination may disclose proptosis, displacement

of the globe, blepharoptosis, and a visible or palpable

mass.[4] NPC infiltration of the anteromedial corner of the

orbit, probably through the nasolacrimal duct, is a rare

phenomenon with only a few reported cases.

In our patient, known anterior nasal cavity tumour

recurrence was biopsy-proven. On three-dimensional

reformatting of images, hypermetabolic soft tissue was

clearly shown extending along the nasolacrimal duct,

connecting the hypermetabolic anterior nasal cavity

mass and medial orbital mass. This is evidence of the

possible NPC invasion route to the anterior orbit through

the nasolacrimal duct. A similar case was reported by

Amrith5 of a 59-year-old woman with NPC recurrence

at the anterior nasal cavity who reported left orbital

swelling with bloody tears. On follow-up CT, a soft

tissue lesion was seen infiltrating bilateral nasolacrimal

ducts from nasal cavity masses, connected superiorly

to the anteromedial mass in the left orbit. Biopsy of

the orbital mass was compatible with NPC recurrence.

Amrith[5] also reported another case of recurrent NPC in

a 33-year-old man 4 years after initial radiotherapy. He

presented with a medial orbital mass and tearing. On

CT scan, bilateral lacrimal sac masses were seen with

extension into bilateral nasolacrimal ducts. Subsequent

biopsy of the orbital mass confirmed it to be recurrent

NPC.

Among few other reported cases of NPC recurrence

involving the nasolacrimal duct and lacrimal sac,

there have often been accompanying symptoms

related to tearing, including epiphora and bloody tears,

resembling a lacrimal sac tumour.[5] [6] [7] These symptoms may be due to obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct and

precede the occurrence of medial orbital mass. Prompt

investigation such as early progress PET-CT or EBV

DNA titre screening may help early detection of tumour

progression.[8] Early initiation of second-line or palliative

treatment may still offer symptomatic relief as in our

patient.

It has been shown by Li et al[9] that the probability of

NPC invasion into structures further away from the

nasopharynx, such as the paranasal sinuses or orbital

apex, is significantly higher in recurrent disease than in

primary disease. One possible explanation suggested by

the authors is that tumour cells of subclinical lesions in

low-dose radiotherapy areas receive mostly sublethal

damage and survive, then continue to split and lead to

tumour recurrence; another explanation is that patients

susceptible to NPC are prone to recurrence, but the

normal structure of the areas adjacent to the nasopharynx

have been destroyed by high-intensity rays during the

first treatment, with the local blood supply reduced and

unfavourable for tumour growth, so the tumour relocates

and occurs far away from the nasopharynx. Whichever

the case, close attention should be paid when examining

follow-up studies, not only at the primary tumour site

at the nasopharynx, but at marginal irradiation zones

peripheral to the nasopharynx where recurrence may

also occur.

CONCLUSION

We report a patient with NPC recurrence with an

uncommon presentation that involved orbital metastasis

from the nasal cavity through the nasolacrimal duct.

Radiological evidence was revealed on a PET-CT

scan. Careful correlation with early clinical symptoms

and radiological findings may allow early detection

of uncommon tumour recurrence. Subsequent early

initiation of second-line or palliative treatment may

improve treatment results and enhance patient care.

REFERENCES

1. Hong Kong Cancer Registry, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Available from: http://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/topten.html. Accessed 8 May 2019.

2. Luo CB, Teng MM, Chen SS, Lirng JF, Guo WY, Chang T. Orbital

invasion in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: evaluation with computed

tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Zhonghua Yi Xue

Za Zhi (Taipei). 1998;61:382-8.

3. Colaco RJ, Betts G, Donne A, Swindell R, Yap BK, Sykes AJ,

et al. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a retrospective review of

demographics, treatment and patient outcome in a single centre.

Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2013;25:171-7. Crossref

4. Shin SC, Hong SL, Lee CH, Cho KS. Orbital metastasis as

the primary presentation of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;82:614-7. Crossref

5. Amrith S. Antero-medial orbital masses associated with

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Singapore Med J. 2002;43:97-9.

6. Huang TT, Chen PR, Hsu YH, Sheen TS, Chang YL, Hsu LP.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma invading the lacrimal apparatus — a

case report. Tzu Chi Med J. 2005;17:349-52.

7. Sia KJ, Tang IP, Kong CK, Tan TY. Nasolacrimal relapse of

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Laryngol Otol. 2012;126:847-50. Crossref

8. Wang WY, Twu CW, Lin WY, Jiang RS, Liang KL, Chen KW,

et al. Plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA screening followed by

18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography in

detecting posttreatment failures of nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Cancer. 2011;117:4452-9. Crossref

9. Li JX, Lu TX, Huang Y, Han F. Clinical characteristics of

recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma in high-incidence area.

ScientificWorldJournal 2012;2012:719754. Crossref