Ultrasound-guided Vacuum-assisted Excision of Papillary Breast Lesions as an Alternative to Surgical Excision: 7-year Experience

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Ultrasound-guided Vacuum-assisted Excision of Papillary Breast Lesions as an Alternative to Surgical Excision: 7-year Experience

CM Chau1, EPY Fung2, CW Wong2, KM Kwok2, AYH Leung2, LKM Wong2, KCK Wong2, WS Mak2, HS Lam2, DHY Cho2

1 Department of Radiology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong

Correspondence: Dr CM Chau, Department of Radiology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong. Email: ccm152@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 1 Jan 2019; Accepted: 12 Feb 2019.

Contributors: All authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the article, and critically revised the article for

important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Approval: This retrospective study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Kowloon Central/Kowloon East Cluster (Ref KC/

KE-18-0128/ER-3). Owing to the retrospective nature of the study, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Acknowledgement: We thank Ms Ellen LM Yu, Research Officer, Clinical Research Centre, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong, who

advised on the statistical methods for data analysis and assisted in implementing these methods.

Abstract

Objective

Removal of papillary breast lesions following percutaneous biopsy is advocated due to their diagnostic

challenges. Image-guided vacuum-assisted excision is a treatment option for managing papillary breast lesions.

The aim of our study was to review our experience in ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted excision (US-VAE) of

papillary breast lesions.

Methods

This was a retrospective review of patients with biopsy-proven papillary breast lesions who underwent

US-VAE from January 2011 to April 2018. The clinical, radiological, and initial biopsy findings and the US-VAE

procedure data were collected. The final histology was reviewed for any evidence of malignancy. Patients were

followed up by clinical assessment and ultrasound. Lesion excision was considered successful removed if no residual

or recurrence was found at follow-up.

Results

A total of 71 patients with 76 papillary lesions underwent US-VAE over a 7-year period. No major

complications were observed. The overall cancer upgrade rate on pathology was 5.3%, with cancer upgrade rates

for papillary lesions with atypia and without atypia of 16.7% and 3.1%, respectively. Mean follow-up time was 12.8

months. Two residual lesions were found during follow-up, for a successful lesion removal rate of 97.2%.

Conclusion

The highly successful lesion removal rate with low residual or recurrence for benign papillary lesions

confirms that US-VAE avoids surgical excision in patients with biopsy-proven papillary lesions. It remains a safe

and effective alternative to surgical excision in managing biopsy-proven papillary lesions.

Key Words: Benign neoplasms/therapy; Breast/surgery; General surgery/instrumentation; Papilloma/therapy;Ultrasonography

中文摘要

超聲引導真空輔助抽吸乳頭狀乳房病灶切除術作為手術切除的替代方法:七年經驗回顧

周智敏、馮寶恩、黃鎮威、郭勁明、梁燕霞、黃嘉敏、黃卓琦、麥詠詩、林漢城、曹慶恩

目的

由於診斷上的困難和挑戰,一般建議經皮活檢診斷的乳頭狀乳房病灶以切除術治療。影像引

導真空輔助抽吸切除術是乳頭狀乳房病灶的治療方案之一。本研究回顧我院進行超聲引導真空輔助

抽吸乳頭狀乳房病灶切除術(US-VAE)的經驗。

方法

回顧分析2011年1月至2018年4月期間進行US-VAE的活檢證實乳頭狀乳房病灶患者。收集臨

床、影像學和初步活檢結果以及US-VAE手術記錄,核對組織學是否有惡性依據。患者進行臨床評估

和超聲檢查隨訪。如在隨訪中未發現殘留或復發會被視為已成功切除病灶。

結果

7年內71名患者共76個乳頭狀乳房病灶接受了US-VAE。圴無嚴重併發症。總體按照病理結果

的癌變升級率為5.3%,而具有不典型增生和無不典型增生的乳頭狀病灶的癌變升級率分別為16.7%和

3.1%。平均隨訪時間為12.8個月。在隨訪期間發現兩個殘留病灶。病灶清除成功率為97.2%。

結論

良性乳頭狀乳房病灶的高成功清除率且低殘留病灶或復發率,表明對於活檢證實乳頭狀乳房病灶患者使用US-VAE可避免手術治療。US-VAE治療活檢證實的乳頭狀乳房病灶是安全有效替代手術切除的方案。

INTRODUCTION

Papillary breast lesions comprise a broad spectrum

ranging from benign papilloma through atypical

papilloma or carcinoma in situ to papillary carcinoma,

and the distinctions among these lesions represent

a continuum that can be difficult to distinguish both

radiologically and pathologically.[1] Together with the

underestimation from fine needle aspiration (FNA) and

core needle biopsy (CNB),[2] [3] [4] which are the commonest

initial diagnostic procedures for ultrasound-detected

breast lesions, this imposes a diagnostic difficulty for

papillary breast lesions.

Removal of percutaneously diagnosed papillary lesions

is advocated by many studies due to the substantial

cancer upgrade rate.[5] [6] [7] However, the drawbacks of

surgical excision for all percutaneously diagnosed

papillary lesions are the surgical risks, high costs, and

long recovery time from surgical operations.

Vacuum-assisted excision has consistently been shown

to be effective.[8] [9] [10] [11] [12] The National Health Service (NHS)

of the UK has recommended the use of image-guided

vacuum-assisted excision to remove benign breast

lesions such as fibroadenomas since 2006 and also for

management of some histological indeterminate B3

lesions.[13] [14]

The aim of our study was to review the outcome and

effectiveness of ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted

excision (US-VAE) of papillary breast lesions at our

institution.

METHODS

We reviewed the data of patients that underwent

US-VAE in Kwong Wah Hospital from January 2011

to April 2018. Patients with prior biopsy-proven benign

papillary lesions were included. We excluded patients

with known untreated malignancy in the same breast.

Data on each patient’s age at diagnosis, sex, and

presenting symptoms were collected from the electronic

patient record. The ultrasound characteristics of the

lesions, including size and distance from the nipple,

were recorded from the ultrasound images or reports.

The assessment categories of the lesions were retrieved

from the reports. The reporting radiologists were using

either the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System

(BI-RADS) by the American College of Radiology or the

UK five-point breast imaging classification by the Royal

College of Radiologists Breast Group. The initial biopsy

methods and their pathology results were collected.

All the US-VAEs were performed by one of five

breast radiologists with 2 to 11 years’ specialised experience in breast imaging. The vacuum-assisted

systems used were either EnCor (7-gauge or 10-gauge

needle) or Mammotome (8-gauge or 11-gauge needle).

The ultrasound images from the biopsy procedure

were reviewed, and the lesion identified using a highfrequency

linear array ultrasound transducer. A solution

of 2% lidocaine with 1:200 000 epinephrine diluted

with normal saline in 1:1 ratio (mean 14 mL) was

injected under the skin and around the lesion as local

anaesthesia. The needle was placed underneath the

lesion and US-VAE of the lesion was performed with a

180° sweep (Figure). Complete removal was attempted

and evidenced by real-time ultrasound. Any incomplete

removal was recorded. A localisation marker was placed

at the excision site after lesion removal. Haemostasis

was first achieved by manual compression; then the

wound was closed with sterile strips followed by a

compression dressing around the chest. Any immediate complications during the procedure were recorded. The

procedure was performed in an outpatient breast clinic

setting and the patient was discharged on the same day

after the procedure. Patients were advised to return to

our breast clinic if there were any complications, such

as breast swelling, bleeding or fever, after the procedure.

Major complications were defined as hospitalisation or

surgery related to the procedure.

Figure. Ultrasonography images during the ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted excision (US-VAE) procedure. (a) The needle is placed deep

into the lesion. (b) The needle aperture (arrow) is opened to ensure lesion was touching the needle aperture. (c) Real-time ultrasonograph

during the VAE procedure showing that the lesion was being sucked into the needle aperture. (d) Ultrasonograph taken to confirm complete

removal of the lesion at the end of excision.

Pathology results from US-VAE were reviewed. Ductal

carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and invasive carcinoma were

considered as cancer upgrades and were referred for

surgical excision. Patients with nonmalignant lesions

were followed up by clinical assessment and ultrasound.

A lesion was considered as successfully removed if no

residual or recurrence was found at follow-up.

Fisher’s exact test was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Between January 2011 and April 2018, of 236 breast

lesions in 228 patients removed with US-VAE, there

were 77 biopsy-proven papillary breast lesions in

72 patients. One lesion was excluded as the patient had

known DCIS in the same breast. In total, there were

76 papillary breast lesions in 71 patients in our study

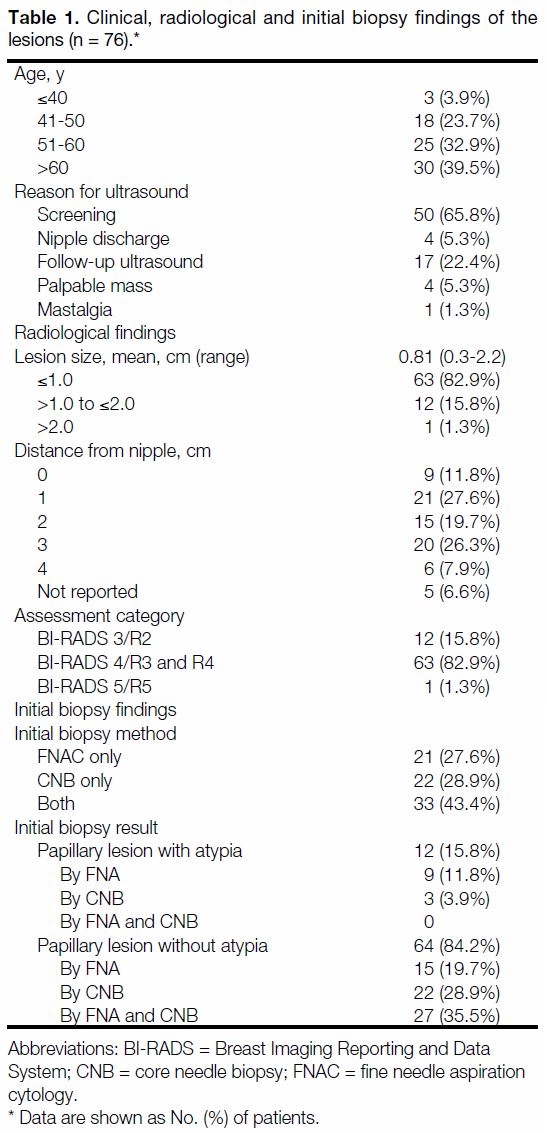

(Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical, radiological and initial biopsy findings of the lesions (n = 76).

Clinical, Radiological, and Initial Biopsy

Findings of Lesions

The mean age at presentation was 56.3 years (range,

36-75 years). All were female patients. The majority of

the lesions were found during routine screening (n = 50,

65.8%) or follow-up ultrasound for other breast lesions

(n = 17, 22.4%).

The mean lesion size was 0.81 cm (range, 0.3 cm-2.2 cm).

The majority of the lesions were ≤1.0 cm (n = 63, 82.9%)

and only one lesion was >2.0 cm. The recorded locations

of the lesions in terms of distance from the nipple were

0 to 4 cm. Subareolar or periareolar lesions were marked

as 0 cm from nipple. There was no indication of the

location in five lesions.

The assessment category of each lesion was assigned

by the radiologist that performed the initial diagnostic

ultrasound before the biopsy. A total of 71 lesions

were categorised according to BI-RADS. Five lesions

were categorised as R3 (indeterminate/probably benign

findings; n = 2) or R4 (findings suspicious of malignancy;

n = 3), according to the UK five-point breast imaging

classification. We had mapped the UK five-point breast

imaging classification to BI-RADS according to the

study by Taylor et al.[15] The overall lesion assessment

categories are listed in Table 1. The majority of the

lesions were categorised as BI-RADS 4 (n = 63, 82.9%).

All the papillary lesions had undergone prior ultrasound-guided

biopsy, either by FNA, CNB, or both, depending

on the operator’s preference. The needle sizes and the

number of samples are summarised in Table 2. The

number of samples obtained from one lesion biopsied

with a 10-gauge needle was not specified. All the

pathology results from initial biopsy showed papillary

lesions. The lesions were further categorised as with

or without atypia. If there was a discrepancy between

the FNA and CNB pathology results, the lesions were

categorised based on the more suspicious pathology. A

total of 12 (15.8%) showed atypia and 64 (84.2%) did

not have atypia. Seven lesions biopsied with both FNA and CNB had had discrepant pathology results, in which

FNA showed atypia but CNB did not in five lesions and

CNB showed atypia but FNA did not in two lesions.

Thus, overall there were nine papillary lesions with

atypia diagnosed by FNA and three by CNB.

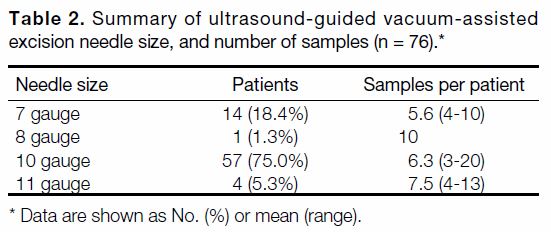

Table 2. Summary of ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted

excision needle size, and number of samples (n = 76)

Ultrasound-guided Vacuum-assisted Excision

Results

All the lesions were confirmed as completely removed

by ultrasonogram. The sample weight of each lesion was

calculated by multiplying the weight of each core16 by

the number of cores. The mean sample weight for lesions

<1 cm was 1.345 g (±0.530; range, 0.336-2.904 g) and

for lesions ≥1 cm was 1.920 g (±1.033; range, 0.588-4.420 g).

No major complication was noted during the

procedures and no patient returned to the breast clinic

for complications after being discharged. One patient

required skin sutures due to a laceration during the

procedure with uneventful wound healing.

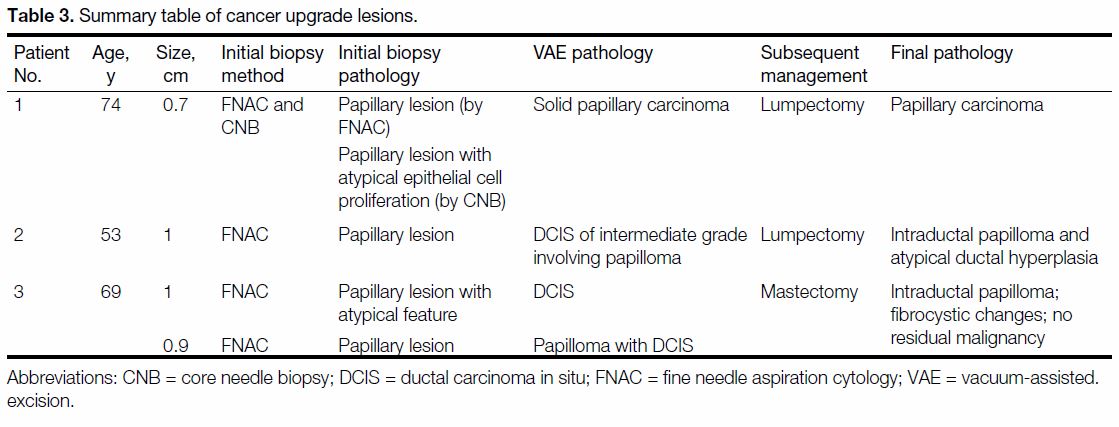

Four malignant lesions were found in three patients

from the final pathology of US-VAE. These included

one DCIS, two DCIS with papilloma, and one solid

papillary carcinoma. The overall cancer upgrade rate

was 5.3%. Among the four malignant lesions, three

lesions had FNA only and one had FNA and CNB as

initial biopsies. Two of them had atypical features on

initial biopsy, identified by FNA and CNB (Table 3).

Thus, the cancer upgrade rate for papillary lesions with

atypia was 16.7% and that for papillary lesions without

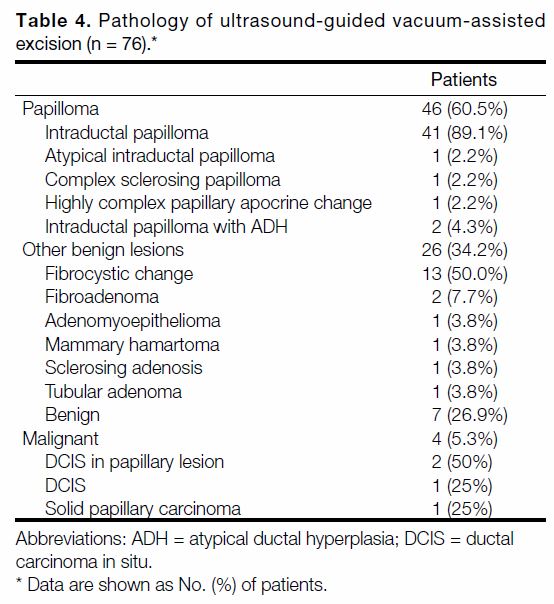

atypia was 3.1% (p = 0.115). The pathologies excised

with US-VAE are listed in Table 4.

Table 3. Summary table of cancer upgrade lesions.

Table 4. Pathology of ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted excision (n = 76).

Follow-up

Four patients had subsequent surgery. The four malignant

lesions in three patients were removed with lumpectomy

or mastectomy (Table 3). Two patients with DCIS

showed no residual malignancy in the final pathology

from surgical excision. One benign lesion underwent

lumpectomy as the pathology from VAE showed

atypical intraductal papilloma. The final pathology from

the lumpectomy was benign intraductal papilloma.

The rest of the 67 patients were followed up clinically

and 51 (76.1%) patients had follow-up ultrasound. The mean follow-up time was 12.8 months (range, 1.3-67.4 months). The overall rate of successful lesion

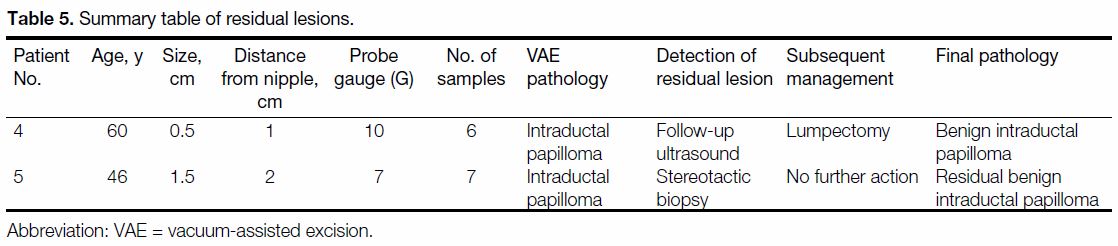

removal was 97.2%. Table 5 shows the handling of

residual pathology in two patients.

Table 5. Summary table of residual lesions.

Lesion size, location, and probe gauge were not

statistically significant predictors of residual lesions.

DISCUSSION

Management of percutaneously diagnosed papillary

lesions has been a challenge for years due to its diagnostic

difficulty and substantial rate of cancer upgrade. The

reported cancer upgrade rate has ranged from 3.1% to

15.8%[5] [6] [7] and lesion removal was advocated in many

different studies.[5] [6] [7] [17] [18] [19] [20] Before the advent of percutaneous

VAE, surgical excision was the treatment of choice for

lesion removal. As more and more papillary lesions were

diagnosed in breast screening, the high costs of labour

and operation theatre time would be a burden to the

healthcare system.[21] Moreover, since the papillary lesions

were indeterminate in biopsy histology with chances

of being a benign papilloma, patients may be reluctant

to undergo surgical excision due to the morbidity and

mortality from surgical and anaesthetic risks.

Image-guided VAE was initially used to improve

diagnostic accuracy for percutaneous biopsy due to

larger cores obtained when compared to conventional

FNA and CNB.[9] [10] Its use has been extended to remove

benign lesions because a larger amount of tissue can be

obtained in one pass, and with better cosmetic results.

US-VAE can be performed as an outpatient procedure in

the clinic and the patient can be discharged on the same

day, resulting in much lower costs than those incurred

with surgical excision.[22]

In our series, a success rate of 97.2% for benign papillary

lesion removal by US-VAE without residual or recurrent

disease was achieved, in line with the reported overall

success rate of 97% to 100% in the literature.[23] [24]

Two residual lesions were found, which raises the

question of how complete removal can be achieved

confidently during the procedure. For US-VAE,

the only evidence of lesion removal is by real-time

ultrasound imaging. However, during the procedure,

there are inevitable small haematomas and oedema at

the procedure site,[25] which may obscure the field and

make it difficult for the operators to determine whether

the lesion is completely removed or not. Some operators

remove breast tissue surrounding the lesions at four more

sampling sites to ensure complete lesion removal but the

results varied.[26] [27] The NHS Breast Screening working

group had suggested a specimen of approximately 4 g

to be equivalent to surgical excision.[28] Also, the working

group did not state the size range of the lesion for their

recommendation. Smaller lesions can be completely

excised with a lower specimen weight.

The two residual lesions in our study occurred at the early

stage (2013 and 2014) since we started US-VAE in 2011.

Salazar et al[29] reported that 11 excisions were required

to acquire skills to perform complete excision in more

than 80% at the end of the US-VAE and 18 excisions

at 6 months. Thus, operator experience is one of the

important factors for successful lesion removal. Centres

performing US-VAE should formulate standardised

training and credentialing for better performance of

US-VAE.

Three papillomas with atypical features were found

(Table 4), namely, one atypical intraductal papilloma

and two intraductal papillomas with atypical ductal

hyperplasia. The atypical intraductal papilloma

underwent surgical excision and final pathology

showed benign papilloma with no atypical or invasive

features. The two intraductal papillomas with ADH

had no recurrence or cancer development during the

follow-up period of 11.0 months and 27.6 months. The

literature shows a low underestimation rate of 0% with

US-VAE.[23] [30] Thus, these lesions can be safely managed by close monitoring after multidisciplinary discussion

and this approach is supported by the consensus from the

UK and Europe.[28] [31]

No major complication was found after US-VAE in our

series. US-VAE has been reported as a safe procedure

with a low rate of complications, ranging from 0% to

9%.[10] [12] [23] [24] [27] [32] [33] The majority of complications included

hematoma and pain, which were usually self-limiting and

did not require further intervention. One of our patients

required suturing due to skin laceration during the

procedure because the lesion was superficially located.

This was considered as a minor complication and we

should inform patients about this potential complication,

especially when the lesion is close to the skin.

In our study, the cancer upgrade rate for papillary lesions

diagnosed by FNA or CNB prior to US-guided VAE was

5.3%, which is compatible with the literature.[6] [7] [18] For

diagnosing papillary lesions with atypia, pathologists

need to assess the size of the area of atypical epithelial

proliferation and sometimes it would be difficult to

distinguish atypical epithelial proliferation within a

papilloma from low-grade DCIS within a papilloma in

the tissue samples,[34] and FNA may miss the small foci of

carcinoma in situ or the foci that are invasive.[35] [36] Thus,

for papillary lesions with atypia diagnosed by FNA or

CNB, surgical excision would be more appropriate

as the next step of management, as included in the

recommendations from the NHS Breast Screening

working group.

There were a few limitations in this study. Our sample

size was small, as was the number of residual lesions.

Thus, we could not identify any statistically significant

factors associated with incomplete excision. Also,

the adequate sample weight for different lesion sizes

may need further study for validation. There would be

selection bias in a retrospective study as the lesion size,

location of the lesion and technical factors may affect

the clinicians’, radiologists’ and patients’ decision on

choosing US-VAE or surgical excision. Only 70.8% of

patients had follow-up ultrasonography examination,

which may have resulted in underestimation of the

residual rate.

In conclusion, our successful lesion removal rate with

low rates of residual or recurrence for benign papillary

lesions confirms that US-VAE spares most patients with

FNA- or CNB-proven papillary lesions from surgical

excision and provides adequate tissue samples for a confident diagnosis guiding subsequent management. It

is a safe and effective alternative to surgical excision in

managing biopsy-proven papillary lesions.

REFERENCES

1. Sohn V, Keylock J, Arthurs Z, Wilson A, Herbert G, Perry J, et al.

Breast papillomas in the era of percutaneous needle biopsy. Ann

Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2979-84. Crossref

2. Houssami N, Ciatto S, Ellis I, Ambrogetti D. Underestimation of

malignancy of breast core–needle biopsy: concepts and precise

overall and category-specific estimates. Cancer. 2007;109:487-95. Crossref

3. Ciatto S, Houssami N, Ambrogetti D, Bianchi S, Bonardi R,

Brancato B, et al. Accuracy and underestimation of malignancy of

breast core needle biopsy: the Florence experience of over 4000

consecutive biopsies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;101:291-7. Crossref

4. Youk JH, Kim EK, Kim MJ, Oh KK. Sonographically guided

14-gauge core needle biopsy of breast masses: a review of

2420 cases with long-term follow-up. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

2008;190:202-7. Crossref

5. Rizzo M, Linebarger J, Lowe MC, Pan L, Gabram SG, Vasquez L,

et al. Management of papillary breast lesions diagnosed on core-needle

biopsy: clinical pathologic and radiologic analysis of 276

cases with surgical follow-up. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:280-7. Crossref

6. Jaffer S, Nagi C, Bleiweiss IJ. Excision is indicated for intraductal

papilloma of the breast diagnosed on core needle biopsy. Cancer.

2009;115:2837-43. Crossref

7. Chang JM, Moon WK, Cho N, Han W, Noh DY, Park IA, et al.

Management of ultrasonographically detected benign papillomas

of the breast at core needle biopsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

2011;196:723-9. Crossref

8. Rajan S, Shaaban AM, Dall BJ, Sharma N. New patient pathway

using vacuum-assisted biopsy reduces diagnostic surgery for B3

lesions. Clin Radiol. 2012;67:244-9. Crossref

9. Simon JR, Kalbhen CL, Cooper RA, Flisak ME. Accuracy and

complication rates of US-guided vacuum-assisted core breast

biopsy: initial results. Radiology. 2000;215:694-7. Crossref

10. Cassano E, Urban LA, Pizzamiglio M, Abbate F, Maisonneuve P,

Renne G, et al. Ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted core breast

biopsy: experience with 406 cases. Breast Cancer Res Treat.

2007;102:103-10. Crossref

11. Chang JM, Han W, Moon WK, Cho N, Noh DY, Park IA, et al.

Papillary lesions initially diagnosed at ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted

breast biopsy: rate of malignancy based on subsequent

surgical excision. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2506-14. Crossref

12. Fine RE, Boyd BA, Whitworth PW, Kim JA, Harness JK,

Burak WE. Percutaneous removal of benign breast masses using a

vacuum-assisted hand-held device with ultrasound guidance. Am

J Surg. 2002;184:332-6. Crossref

13. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, UK Government.

Image-guided vacuum-assisted excision biopsy of benign breast

lesions. 2006. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg156/resources/imageguided-vacuumassi.... Accessed 23 Sep 2018.

14. National Health Service. NHS Breast Screening Programme.

Clinical guidance for breast cancer screening assessment.

2016. Available from: https://associationofbreastsurgery.org.uk/media/1414/nhs-bsp-clinical-gu.... Accessed 23 Sep 2018.

15. Taylor K, Britton P, O’Keeffe S, Wallis MG. Quantification of the

UK 5-point breast imaging classification and mapping to BI-RADS to facilitate comparison with international literature. Br J Radiol.

2011;84:1005-10. Crossref

16. Preibsch H, Baur A, Wietek BM, Krämer B, Staebler A,

Claussen CD, et al. Vacuum-assisted breast biopsy with 7-gauge,

8-gauge, 9-gauge, 10-gauge, and 11-gauge needles: how many

specimens are necessary? Acta Radiologica. 2015;56:1078-84. Crossref

17. Mercado CL, Hamele-Bena D, Oken SM, Singer CI, Cangiarella J.

Papillary lesions of the breast at percutaneous core-needle biopsy.

Radiology. 2006;238:801-8. Crossref

18. Sakr R, Rouzier R, Salem C, Antoine M, Chopier J, Daraï E, et al.

Risk of breast cancer associated with papilloma. Eur J Surg Oncol.

2008;34:1304-8. Crossref

19. Tatarian T, Sokas C, Rufail M, Lazar M, Malhotra S, Palazzo JP,

et al. Intraductal papilloma with benign pathology on breast core

biopsy: to excise or not? Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:2501-7. Crossref

20. Leithner D, Kaltenbach B, Hödl P, Möbus V, Brandenbusch V,

Falk S, et al. Intraductal papilloma without atypia on image-guided

breast biopsy: upgrade rates to carcinoma at surgical excision.

Breast Care (Basel). 2018;13:364-8. Crossref

21. Fernández-García P, Marco-Doménech SF, Lizán-Tudela L,

Ibáñez-Gual MV, Navarro-Ballester A, Casanovas-Feliu E. The

cost effectiveness of vacuum-assisted versus core-needle versus

surgical biopsy of breast lesions. Radiologia. 2017;59:40-6. Crossref

22. Alonso-Bartolomé P, Vega-Bolívar A, Torres-Tabanera M,

Ortega E, Acebal-Blanco M, Garijo-Ayensa F, et al. Sonographically

guided 11-G directional vacuum-assisted breast biopsy as an

alternative to surgical excision: utility and cost study in probably

benign lesions. Acta Radiol. 2004;45:390-6. Crossref

23. Kim MJ, Kim EK, Kwak JY, Son EJ, Park BW, Kim SI, et al.

Nonmalignant papillary lesions of the breast at US-guided

directional vacuum-assisted removal: a preliminary report. Eur

Radiol. 2008;18:1774-83. Crossref

24. Ko KH, Jung HK, Youk JH, Lee KP. Potential application of

ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted excision (US-VAE) for well-selected

intraductal papillomas of the breast: single-institutional

experiences. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:908-13. Crossref

25. Fine RE, Whitworth PW, Kim JA, Harness JK, Boyd BA,

Burak Jr WE. Low-risk palpable breast masses removed using a

vacuum-assisted hand-held device. Am J Surg. 2003;186:362-7. Crossref

26. Kim SY, Kim EK, Lee HS, Kim MJ, Yoon JH, Koo JS, et al. Asymptomatic benign papilloma without atypia diagnosed at

ultrasonography-guided 14-gauge core needle biopsy: which

subgroup can be managed by observation? Ann Surg Oncol.

2016;23:1860-6. Crossref

27. Youk JH, Kim EK, Kwak JY, Son EJ, Park BW, Kim SI. Benign

papilloma without atypia diagnosed at US-guided 14-gauge core-needle

biopsy: clinical and US features predictive of upgrade to

malignancy. Radiology. 2011;258:81-8. Crossref

28. Pinder SE, Shaaban A, Deb R, Desai A, Gandhi A, Lee AH, et al.

NHS Breast Screening multidisciplinary working group guidelines

for the diagnosis and management of breast lesions of uncertain

malignant potential on core biopsy (B3 lesions). Clin Radiol.

2018;73:682-92. Crossref

29. Salazar JP, Miranda I, De Torres J, Rus MN, Espinosa-Bravo M,

Esgueva A, et al. Percutaneous ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted

excision of benign breast lesions: A learning curve to assess

outcomes. Br J Radiol. 2019;92:20180626. Crossref

30. Grady I, Gorsuch H, Wilburn-Bailey S. Ultrasound-guided,

vacuum-assisted, percutaneous excision of breast lesions: an

accurate technique in the diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia.

J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:14-7. Crossref

31. Rageth CJ, O’Flynn EA, Comstock C, Kurtz C, Kubik R,

Madjar H, et al. First International Consensus Conference on lesions

of uncertain malignant potential in the breast (B3 lesions). Breast

Cancer Res Treat. 2016;159:203-13. Crossref

32. Maxwell AJ. Ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted excision of

breast papillomas: review of 6-years experience. Clin Radiol.

2009;64:801-6. Crossref

33. Kim MJ, Park BW, Kim SI, Youk JH, Kwak JY, Moon HJ, et al.

Long-term follow-up results for ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted

removal of benign palpable breast mass. Am J Surg. 2010;199:1-7. Crossref

34. Page DL, Salhany KE, Jensen RA, Dupont WD. Subsequent breast

carcinoma risk after biopsy with atypia in a breast papilloma.

Cancer. 1996;78:258-66. Crossref

35. Michael CW, Buschmann B. Can true papillary neoplasms of breast

and their mimickers be accurately classified by cytology? Cancer.

2002;96:92-100. Crossref

36. Gomez-Aracil V, Mayayo E, Azua J, Arraiza A. Papillary

neoplasms of the breast: clues in fine needle aspiration cytology.

Cytopathology. 2002;13:22-30. Crossref

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| v23n4_Ultrasound.pdf | 550.51 KB |