Benign Soft Tissue and Osseous Tumours of the Hand: a Pictorial Essay

PICTORIAL ESSAY

Benign Soft Tissue and Osseous Tumours of the Hand:

a Pictorial Essay

WI Sit, SKS Tse, PY Chu, KKL Lo

Department of Radiology and Organ Imaging, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

Correspondence: Dr WI Sit, Department of Radiology and Organ Imaging, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong.. Email: sitsitkathy@gmail.com

Submitted: 12 Oct 2018; Accepted: 27 Dec 2018.

Contributors: All authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript

for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This pictorial essay received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Kowloon Central/Kowloon East Cluster Research Ethics Committee (Ref KC/KE-20-0023/

ER-3). The patients provided written informed consent for all treatments and procedures.

INTRODUCTION

Both soft tissue and osseous lesions of the hand are

commonly encountered in everyday clinical practice.

The majority of these lesions are benign, and imaging is

often needed to determine the nature of the lesion. Some

lesions demonstrate characteristic features that enable

diagnosis without intervention. For soft tissue lesions,

plain radiographs have a limited role in diagnosis but

are useful to demonstrate calcification or mineralisation.

Ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

play an important role in characterisation of soft tissue

masses of the hand. Ultrasonography can differentiate

cystic from non-cystic masses and MRI can further

characterise the latter. Benign primary bone tumours of

the hand are often found incidentally during presentation

of unrelated injuries or pain due to pathological fracture.

Radiography is usually the first imaging of choice with

computed tomography or MRI reserved for complex

cases. It is important to be familiar with the variety of

lesions that can occur in the hand so that appropriate

clinical management can be instigated and unnecessary

interventions avoided. In this article, we review the

imaging findings of common benign hand lesions with

attention to their discriminating features.

BENIGN SOFT TISSUE TUMOURS

Ganglion Cyst

Ganglion cysts are the most commonly encountered

soft tissue mass in the hand and wrist region.[1] They tend

to occur in adults, with a female predominance. The

prevalence of ganglion cysts in the hand and wrist region

has been reported in up to 51% of the asymptomatic adult

population.[1] The most common location is in the dorsum

of the wrist, typically close to the scapholunate joint.

Other less common sites include the volar aspect of the

wrist and flexor tendon sheath of the fingers. Ganglion

cysts are thought to represent degeneration of connective

tissue caused by chronic irritation.[2] A tendon sheath cyst

consists of a special ganglion cyst subtype located along

the course of a tendon sheath. Tendon sheath cysts should

be distinguished from the rarer intratendinous cysts that

are believed to result from recurrent injury to the tendon

with subsequent cystic degeneration. Intratendinous

ganglia are clinically relevant because they weaken

the structure of tendons and may predispose them to

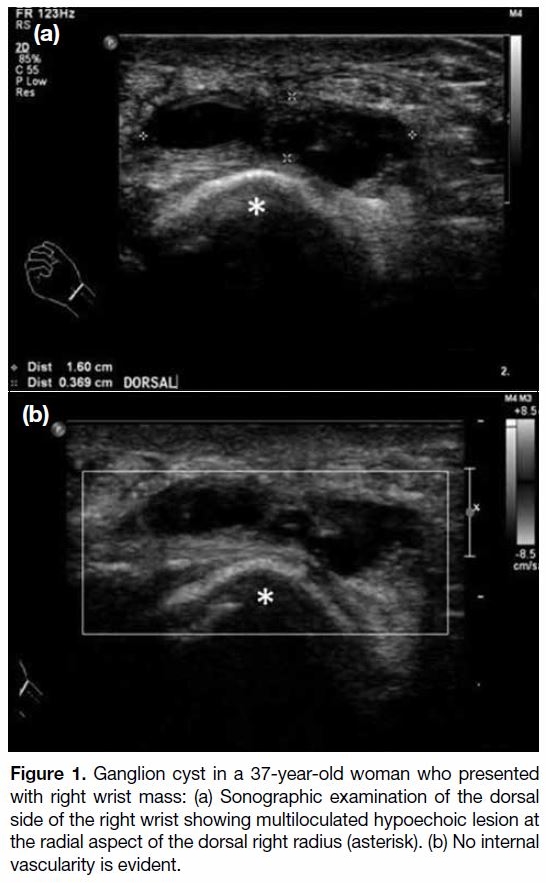

rupture.[3] Diagnosis is usually made by ultrasonography

(Figure 1). On ultrasonography scans, ganglion cysts

appear as unilocular or multilocular anechoic to

hypoechoic lesions with posterior acoustic enhancement.

Figure 1. Ganglion cyst in a 37-year-old woman who presented

with right wrist mass: (a) Sonographic examination of the dorsal

side of the right wrist showing multiloculated hypoechoic lesion at

the radial aspect of the dorsal right radius (asterisk). (b) No internal

vascularity is evident.

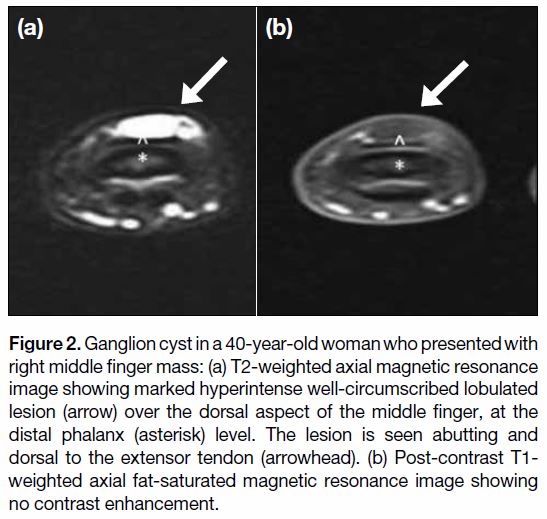

Occasionally, the neck of the lesion may demonstrate

extension towards the adjacent joint. On MRI scans

(Figure 2), ganglion cysts are seen as well circumscribed

unilocular or multilocular cystic lesions without

corresponding contrast enhancement. Sometimes, they

may demonstrate an isointense or hyperintense T1 signal

due to proteinaceous content or haemorrhage.

Figure 2. Ganglion cyst in a 40-year-old woman who presented with

right middle finger mass: (a) T2-weighted axial magnetic resonance

image showing marked hyperintense well-circumscribed lobulated

lesion (arrow) over the dorsal aspect of the middle finger, at the

distal phalanx (asterisk) level. The lesion is seen abutting and

dorsal to the extensor tendon (arrowhead). (b) Post-contrast T1-weighted axial fat-saturated magnetic resonance image showing

no contrast enhancement.

Epidermoid Inclusion Cyst

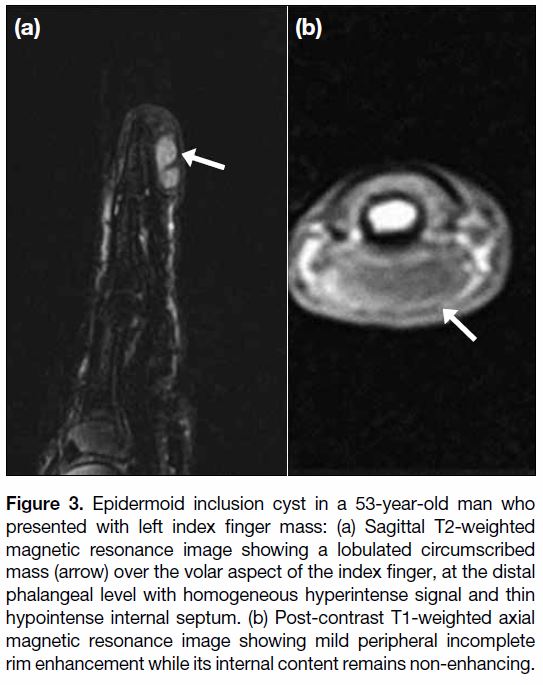

Epidermoid cyst formation (Figure 3) results from

proliferation of surface epidermal cells within the

confined space of the dermis. It is a common benign

cystic lesion that can occur anywhere in the body with

about 10% found in the upper limbs. It is commonly

seen secondary to trauma with implantation of epithelial

squames into the dermis. In the hands, it is usually

seen within subcutaneous tissue at the finger pulps. It

can also cause adjacent bony erosion that is evident on

radiograph or computed tomography. On MRI scan, it is seen as a well-circumscribed lesion with variable

signal intensity on T2-weighted sequence depending

on the chemical composition. Lesions with a high

lipid content will demonstrate hyperintense signal on

both T1- and T2-weighted images, whereas lesions

with keratin and microcalcifications will demonstrate low signal intensity on T2-weighted images. After

administration of gadolinium contrast, there is a lack

of enhancement in uncomplicated cases. Peripheral rim

enhancement is possible with underlying inflammatory

or infective changes.[4] In cases of ruptured epidermal

cyst, MRI scan may show thick and irregular peripheral

rim enhancement, surrounding soft tissue reactions,

and/or variable septa, therefore simulating an infectious

or neoplastic lesion. It might resemble some malignant

soft tissue tumours with central necrosis and these should

be included in the differential diagnosis list.[5]

Figure 3. Epidermoid inclusion cyst in a 53-year-old man who

presented with left index finger mass: (a) Sagittal T2-weighted

magnetic resonance image showing a lobulated circumscribed

mass (arrow) over the volar aspect of the index finger, at the distal

phalangeal level with homogeneous hyperintense signal and thin

hypointense internal septum. (b) Post-contrast T1-weighted axial

magnetic resonance image showing mild peripheral incomplete

rim enhancement while its internal content remains non-enhancing.

Giant Cell Tumours of the Tendon Sheath

Tenosynovial giant cell tumours are a group of generally

benign soft tissue tumours with common histological

findings. Previously termed villonodular tenosynovitis,

the tumours are commonly found in the hand region.[6]

The tumours are lobulated, well circumscribed and

at least partially covered by a fibrous capsule. Their

microscopic appearance is variable, depending on the

proportion of mononuclear cells, multinucleated giant

cells, foamy macrophages, and siderophages and the

amount of stroma. Haemosiderin deposits are virtually

always identified.[7] Tenosynovial giant cell tumours can

be roughly divided into two distinct forms: localised

and diffuse. The localised form primarily occurs extra-articularly

in the tendon sheaths of the hand and foot, or

sometimes in bursa; whereas the diffuse form occurs in

larger joints with a more aggressive growth pattern and

associated with a higher recurrence rate. The aetiology of

giant cell tumour of the tendon sheath remains uncertain.

They usually present as a painless mass in the hands

or feet with non-specific clinical features and are seen

close to a joint or tendons on imaging. Pressure erosion

in adjacent bone can be seen on plain radiographs in

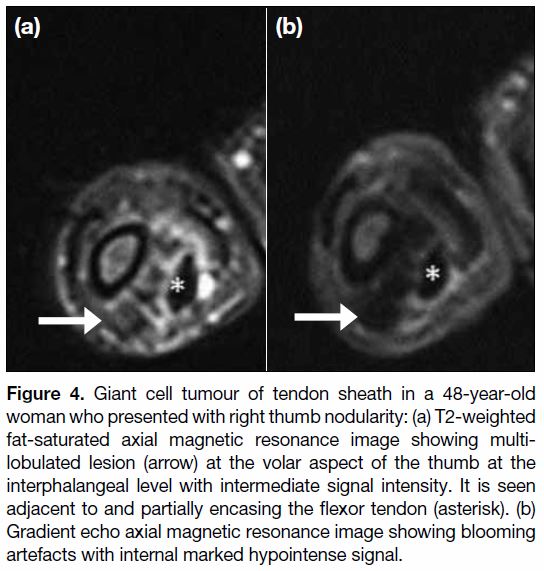

10% to 20% of cases.[8] MRI is currently the optimal

modality for preoperative assessment of tumour size,

extent and invasion of adjacent joint and tenosynovial

space.[9] On MRI scans (Figure 4), the tumour has a low

signal intensity on T1-weighted imaging and variable,

but usually low to intermediate, signal intensity on

T2-weighted imaging. There is moderate contrast

enhancement after intravenous gadolinium contrast

medium injection. Susceptibility artefact on gradient

echo sequence is typical due to haemosiderin deposition.

This is rarely seen in other masses and serves as a useful

feature to differentiate from other soft tissue lesions in

the hand.

Figure 4. Giant cell tumour of tendon sheath in a 48-year-old

woman who presented with right thumb nodularity: (a) T2-weighted

fat-saturated axial magnetic resonance image showing multi-lobulated

lesion (arrow) at the volar aspect of the thumb at the

interphalangeal level with intermediate signal intensity. It is seen

adjacent to and partially encasing the flexor tendon (asterisk). (b)

Gradient echo axial magnetic resonance image showing blooming

artefacts with internal marked hypointense signal.

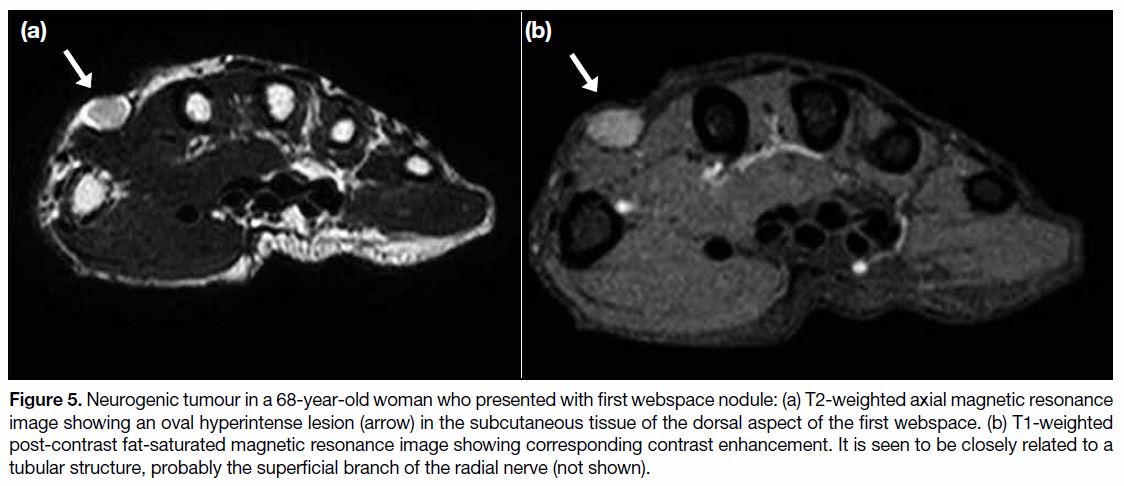

Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumour

Benign peripheral nerve sheath tumours include schwannomas and neurofibromas. They are commonly

found in the forearm and hand region. Schwannomas

arise from the Schwann cells surrounding the nerve

whereas neurofibromas arise from the central nerve

fascicles. Schwannomas tend to occur in larger and

deeper nerves whereas neurofibromas tend to arise from

smaller cutaneous nerves.[10] Clinically, they are usually

seen in adults as a painless slow-growing mass. Most are

not associated with neurofibromatosis. Ultrasonography

shows a fusiform hypoechoic lesion with a “dural tail”

representing the entering and exiting nerve. This may be

difficult to visualise in smaller and superficial cases. On

MRI (Figure 5), they are generally of low-to-intermediate

signal intensity on T1-weighted sequence, high signal

intensity on T2-weighted sequence with homogeneous

contrast enhancement. For larger lesions, target sign with

central T2 hypointense signal may be observed, more

frequently in neurofibromas. Schwannomas can undergo

cystic or fatty degeneration. Features including large

size (>5 cm), infiltrative margins, marked heterogeneity

and rapid growth should raise concern about underlying

malignant change.[11]

Figure 5. Neurogenic tumour in a 68-year-old woman who presented with first webspace nodule: (a) T2-weighted axial magnetic resonance

image showing an oval hyperintense lesion (arrow) in the subcutaneous tissue of the dorsal aspect of the first webspace. (b) T1-weighted

post-contrast fat-saturated magnetic resonance image showing corresponding contrast enhancement. It is seen to be closely related to a

tubular structure, probably the superficial branch of the radial nerve (not shown).

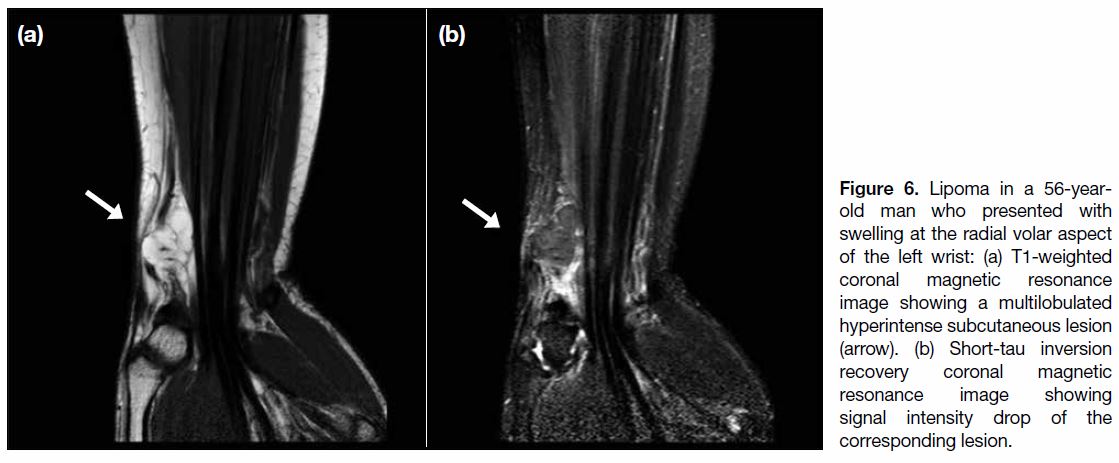

Lipoma

Lipomas are the most common soft tissue tumour in

adults. They are only occasionally seen in the hand and

wrist regions, and account for only 5% of all lipomas

occurring in the upper limb.[12] Clinically, they present

as a painless slow-growing mass, typically at the thenar or hypothenar eminence. Compression on adjacent

nerves or vessels may occur in cases where they are in a

confined space such as the carpal tunnel. Characteristic

sonographic features of a lipoma are an encapsulated

hyperechoic lesion with fine linear internal echogenic

echos.[13] However, the echogenicity may be variable.

On MRI (Figure 6), lipomas show homogeneous

hyperintense signal on T1-weighted sequence with

corresponding signal intensity drop on short-tau

inversion recovery or fat-saturated sequence. Thick

enhancing septation and nodular or a solid component

raises suspicion for atypical lipoma and liposarcoma.[14]

Figure 6. Lipoma in a 56-year-old

man who presented with

swelling at the radial volar aspect

of the left wrist: (a) T1-weighted

coronal magnetic resonance

image showing a multilobulated

hyperintense subcutaneous lesion

(arrow). (b) Short-tau inversion

recovery coronal magnetic

resonance image showing

signal intensity drop of the

corresponding lesion.

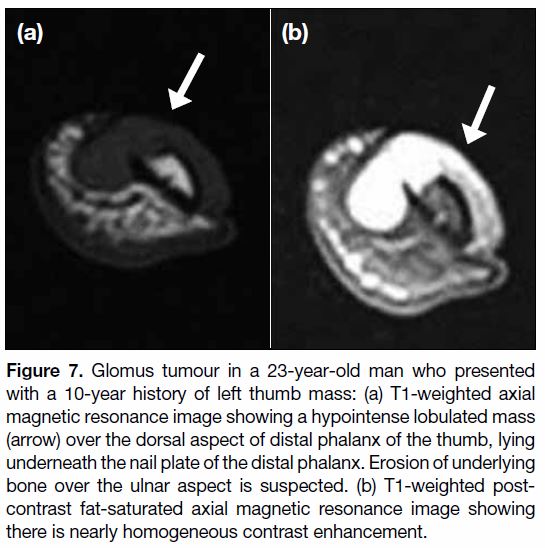

Glomus Tumours

Glomus tumours typically occur in young adults but may

occur at any age. There is no sex predilection except in

subungual lesions that are far more common in women.[7]

A glomus tumour is a benign proliferation of cells

from the glomus body that is involved in regulation of

vascular flow for temperature control. It is occasionally

seen in the hand region, accounting for about 1% of all

hand tumours.[7] Typically, they are seen as subungual

masses in the fingertips. They may present with pain,

temperature sensitivity and point tenderness.[15] Pressure

erosion may also be seen on radiographs. On ultrasound scans, they appear as a non-specific, solid, hypoechoic

mass beneath the nail, possibly with associated erosion

of the underlying phalangeal bone. The high-velocity

flow in intratumoural shunt vessels causes this lesion

to be hypervascular on colour Doppler imaging, and

is diagnostic.[16] On MRI (Figure 7), glomus tumours

demonstrate low signal intensity on T1-weighted

sequence with homogeneous hyperintense signal on

T2-weighted sequence and intense contrast enhancement.

magnetic resonance angiography is a useful non-invasive

adjunct to conventional MRI for establishing

the diagnosis of glomus tumour. Typical magnetic

resonance angiographic findings include areas of strong

enhancement in the arterial phase and tumour blush, with

increase in size in the delayed phase.[16] The characteristic

location at the subungual region with the above imaging

features allows its differentiation from other fingertip

lesions. MRI remains the imaging of choice in suspected

recurrent cases after surgery.[17]

Figure 7. Glomus tumour in a 23-year-old man who presented

with a 10-year history of left thumb mass: (a) T1-weighted axial

magnetic resonance image showing a hypointense lobulated mass

(arrow) over the dorsal aspect of distal phalanx of the thumb, lying

underneath the nail plate of the distal phalanx. Erosion of underlying

bone over the ulnar aspect is suspected. (b) T1-weighted post-contrast

fat-saturated axial magnetic resonance image showing

there is nearly homogeneous contrast enhancement.

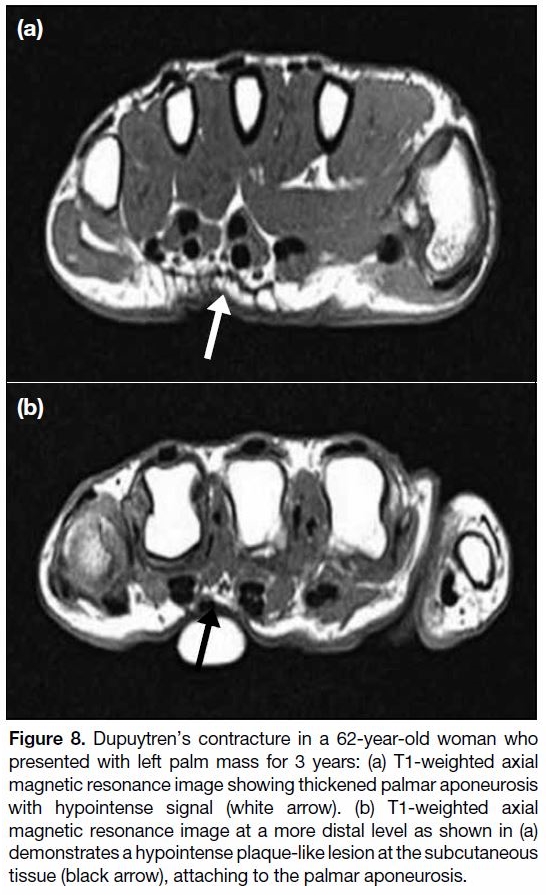

Dupuytren’s Contracture

Dupuytren’s contracture or palmar fibromatosis is a

fibrosing condition that typically presents as painless

subcutaneous nodularity over the palmar surface of the

hand.[18] The disease most commonly occurs in patients

aged >65 years with a male predominance. It is considered

the most common of the superficial fibromatoses and

is thought to affect 1% to 2% of the population. These

nodules can slowly progress to cords and bands and may

cause flexion contracture secondary to fibrous attachment to the underlying tendon sheath. On ultrasound scans, they

are seen as subcutaneous nodules superficial to the flexor

tendons. These lesions are typically found at the level

of the distal palmar crease, commonly with an epicentre

at the distal metacarpal, most commonly the fourth

digit.[19] On MRI (Figure 8), Dupuytren’s contracture is

seen as nodularity or cord-like superficial masses that

arise from the palmar aponeurosis. Typically, these

lesions are of low signal intensity on all pulse sequences

without contrast enhancement. Occasionally, they may

show intermediate signal intensity on both T1- and T2-

weighted images with contrast enhancement, possibly

due to a higher cellular component.

Figure 8. Dupuytren’s contracture in a 62-year-old woman who

presented with left palm mass for 3 years: (a) T1-weighted axial

magnetic resonance image showing thickened palmar aponeurosis

with hypointense signal (white arrow). (b) T1-weighted axial

magnetic resonance image at a more distal level as shown in (a)

demonstrates a hypointense plaque-like lesion at the subcutaneous

tissue (black arrow), attaching to the palmar aponeurosis.

Venous Malformation

Vascular malformations can be subcategorized according

to their flow dynamics into low and high flow types.[20]

Low flow types include venous, lymphatic, capillary-venous and capillary-lymphatic-venous malformations.

The presence of an arterial component indicates a high

flow lesion that includes arteriovenous malformations and arteriovenous fistulas. Venous malformation

(Figures 9 and 10) is the most common peripheral

vascular malformation, usually seen in the head and neck

region, trunk and extremities. Venous malformation

typically presents as a soft, compressible and non-pulsatile

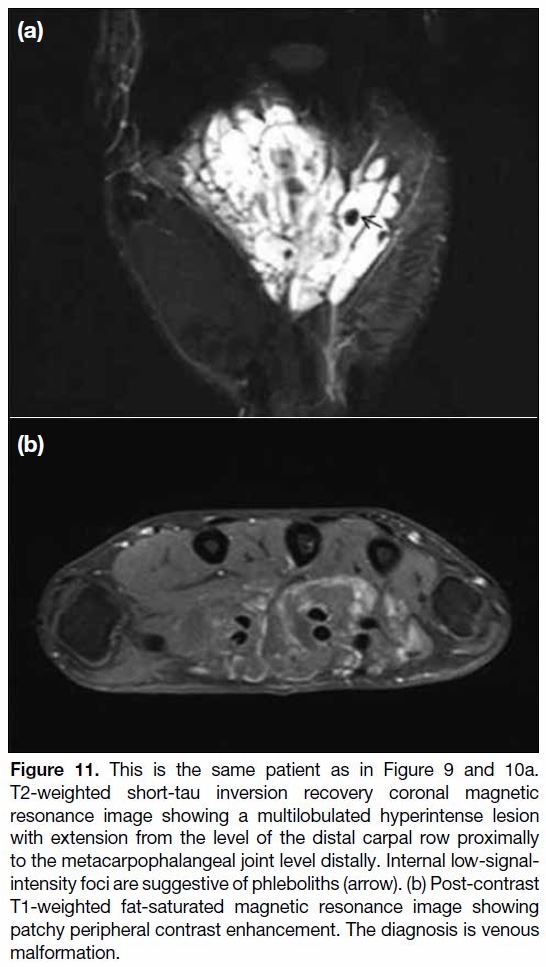

slow-growing mass. On MRI (Figure 11),

vascular malformations are seen as infiltrative lobulated

lesions without significant mass effect, with hyperintense

T2 signal and gradual enhancement on post-contrast

images. Phleboliths may be present. No flow void is

demonstrated. Delayed contrast-enhanced sequences are

also helpful in demonstrating any connection between

the malformations and deeper venous vessels. This is

an important detail to confirm prior to intervention since

these lesions have been linked to a greater risk of deep

venous thrombosis.[21]

Figure 9. An 18-year-old woman presented with right palm mass

for 1 year: Frontal radiograph of the right hand showing a tiny

opacity (arrow) over the radial aspect of the third metacarpal-phalangeal

joint. It could represent a phlebolith. Otherwise there is

no focal bone lesion.

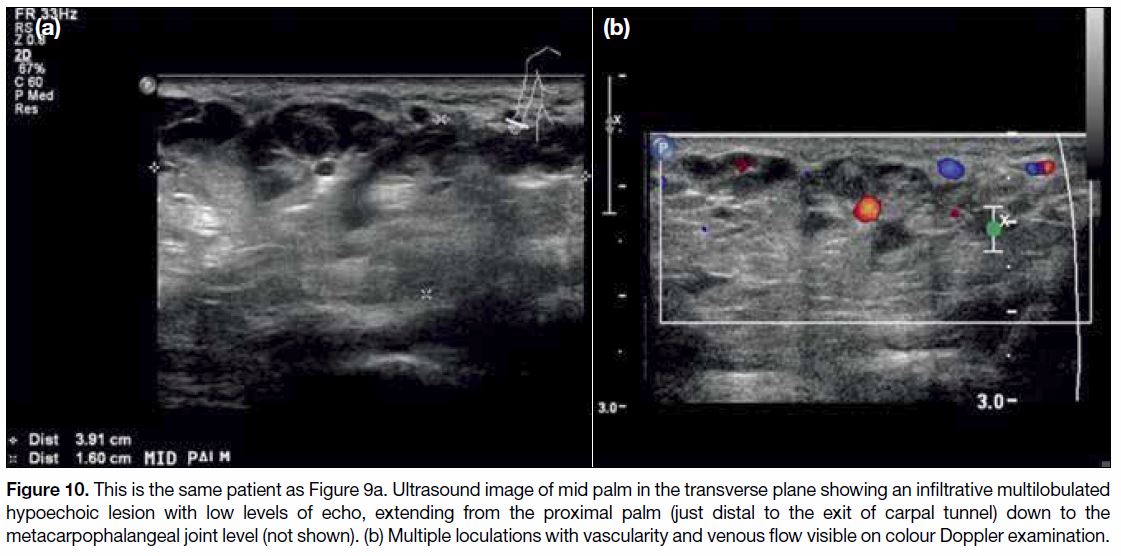

Figure 10. This is the same patient as Figure 9a. Ultrasound image of mid palm in the transverse plane showing an infiltrative multilobulated

hypoechoic lesion with low levels of echo, extending from the proximal palm (just distal to the exit of carpal tunnel) down to the

metacarpophalangeal joint level (not shown). (b) Multiple loculations with vascularity and venous flow visible on colour Doppler examination.

Figure 11. This is the same patient as in Figure 9 and 10a.

T2-weighted short-tau inversion recovery coronal magnetic

resonance image showing a multilobulated hyperintense lesion

with extension from the level of the distal carpal row proximally

to the metacarpophalangeal joint level distally. Internal low-signal-intensity

foci are suggestive of phleboliths (arrow). (b) Post-contrast

T1-weighted fat-saturated magnetic resonance image showing

patchy peripheral contrast enhancement. The diagnosis is venous

malformation.

Aneurysm/Pseudoaneurysm

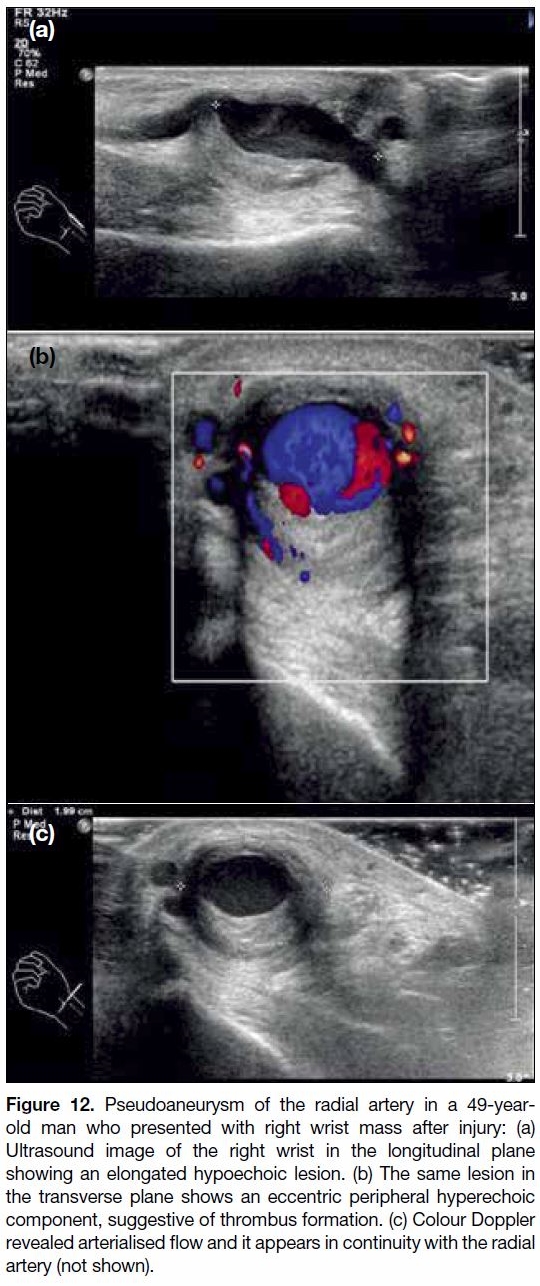

Aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms in the hand are

occasionally seen in clinical practice.[22] Pseudoaneurysms

usually occur secondary to trauma but may be iatrogenic

following arterial puncture. True aneurysms are

uncommon and may be associated with underlying

vasculitis. On ultrasound scans (Figure 12), aneurysms

and pseudoaneurysms demonstrate turbulent flow

with a characteristic yin-yang sign on colour Doppler

images. A to-and-fro pattern may be seen with pulsed

Doppler images. Signal intensity on MRI is variable,

depending on the presence of thrombus or turbulent flow.

Figure 12. Pseudoaneurysm of the radial artery in a 49-year-old

man who presented with right wrist mass after injury: (a)

Ultrasound image of the right wrist in the longitudinal plane

showing an elongated hypoechoic lesion. (b) The same lesion in

the transverse plane shows an eccentric peripheral hyperechoic

component, suggestive of thrombus formation. (c) Colour Doppler

revealed arterialised flow and it appears in continuity with the radial

artery (not shown).

Generally, aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms are slightly

hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted sequence with

signal void. Susceptibility artefact may be demonstrated

in the presence of thrombosis. Sometimes, continuity

with the parent artery is seen. These characteristic

imaging features allow diagnosis and avoid unnecessary

and dangerous biopsy.

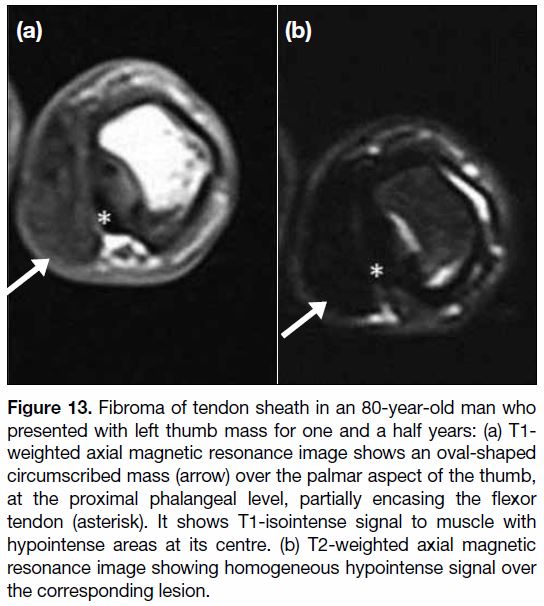

Fibroma of the Tendon Sheath

Fibroma of the tendon sheath is a rare condition and

most (around 82%) are found in the hand and wrist

region.[9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] [23] It is usually seen in adults (20-50 years old)

with a male predominance. It is composed of well-circumscribed

nodules on histology that are typically

paucicellular, containing spindled fibroblasts embedded

in a collagenous stroma.[7] Clinically, fibromas manifest as painless slow-growing masses, typically well-circumscribed

and small (<3 cm) with close proximity

to a tendon or tendon sheath on imaging. On MRI

(Figure 13), fibromas typically have a signal intensity

equal to or lower than that of skeletal muscle on both

T1- and T2-weighted sequences with a variable contrast enhancement pattern.[24] However, the T2 signal can be

variable if areas of increased cellularity or myxoid change

are present.[25] No susceptibility artefact is demonstrated

on gradient echo sequence. The lack of blooming

artefact in fibroma is helpful in differentiation from giant

cell tumour of tendon sheath that may also present as a

low signal lesion on both T1- and T2-weighted sequence

on MRI. They also tend to have a lower signal on

T2-weighted images and show less enhancement with

intravenous contrast material compared with giant cell

tumour of tendon sheath.[26]

Figure 13. Fibroma of tendon sheath in an 80-year-old man who

presented with left thumb mass for one and a half years: (a) T1-weighted axial magnetic resonance image shows an oval-shaped

circumscribed mass (arrow) over the palmar aspect of the thumb,

at the proximal phalangeal level, partially encasing the flexor

tendon (asterisk). It shows T1-isointense signal to muscle with

hypointense areas at its centre. (b) T2-weighted axial magnetic

resonance image showing homogeneous hypointense signal over

the corresponding lesion.

Fibrolipomatous Hamartoma

Also known as neural fibrolipoma or perineural or

intraneural lipoma, a fibrolipomatous hamartoma is

comprised of hypertrophic mature fat and fibroblasts

along the perineurium, surrounding the nerve

bundles within the nerve sheath. It is a rare benign

neoplasm leading to enlargement of the affected nerve,

with predilection at the median nerve. Clinically,

fibrolipomatous hamartomas present as slow-growing

masses at the volar aspect of the hand and wrist region.

They may be associated with macrodactyly (Figure 14),

a condition known as macrodystrophia lipomatosa.

Diagnosis can be made by ultrasonography or MRI,

with longitudinally orientated fusiform structures

representing enlarged nerve fascicles, giving a spaghetti-like

appearance on coronal planes and coaxial cable appearance on axial images (Figure 15).[27] There will

be areas of high and low T1 signal intensity within the

lesion representing the fatty and fibrous components,

respectively.

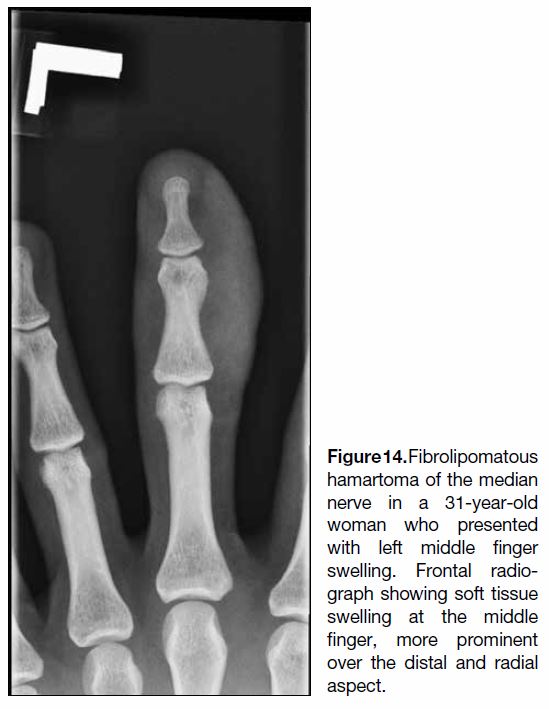

Figure 14. Fibrolipomatous

hamartoma of the median

nerve in a 31-year-old

woman who presented

with left middle finger

swelling. Frontal radio-graph showing soft tissue

swelling at the middle

finger, more prominent

over the distal and radial

aspect.

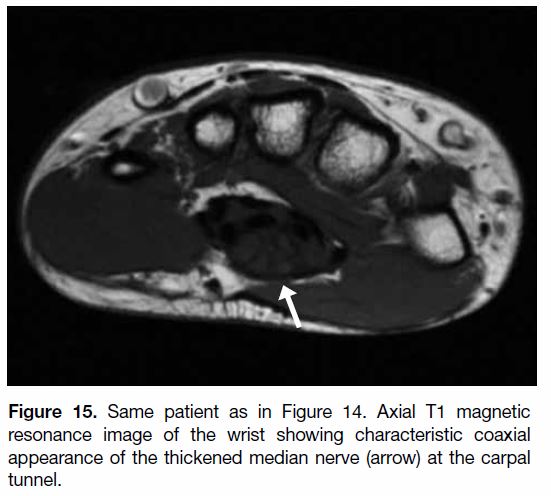

Figure 15. Same patient as in Figure 14. Axial T1 magnetic

resonance image of the wrist showing characteristic coaxial

appearance of the thickened median nerve (arrow) at the carpal

tunnel.

BENIGN BONE TUMOURS

Enchondroma

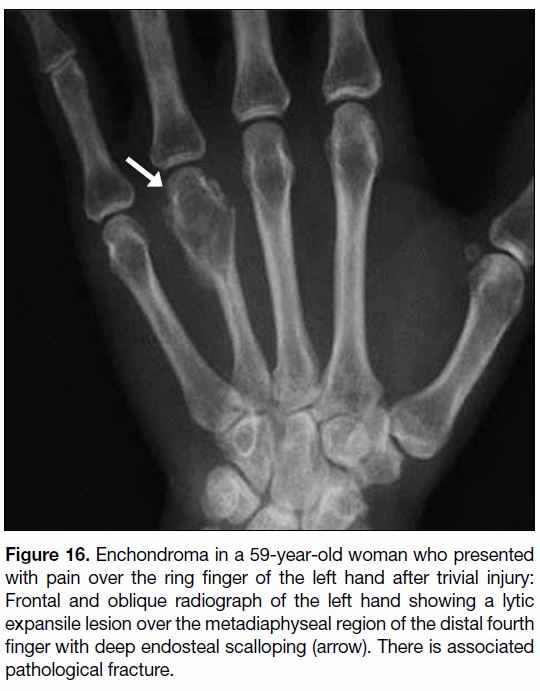

Enchondroma (Figure 16) is the most common benign

bone tumour of the hand, often asymptomatic and

found incidentally on radiographs for an unrelated

indication. Associated pain should raise concern for an

underlying pathological fracture. Enchondroma in the

hand is classically lobular in contour and associated with

endosteal scalloping, commonly deep and associated

with cortical thinning and a variable degree of bone

expansion.[27] A ring and arc pattern of matrix may be

present. Malignant transformation is rare but should be

considered in cases of interval growth, local periosteal

reaction or severe new pain.[28] In the long bones, the

destruction of more than two thirds of the thickness of

the cortex in a chondroid lesion would raise concern

for underlying low-grade chondrosarcoma.[29] [30] Multiple

enchondromatosis, also known as Ollier’s disease,

typically demonstrates multiple enchondromas in the

hand with deformity. The metacarpal bones are more

frequently involved than the phalanges. Malignant

transformation has been reported in 20% to 45.8% of

pre-existing enchondromatosis cases and in 52% to 57.1%

of patients with Maffucci’s syndrome in a recent study.[31]

Figure 16. Enchondroma in a 59-year-old woman who presented

with pain over the ring finger of the left hand after trivial injury:

Frontal and oblique radiograph of the left hand showing a lytic

expansile lesion over the metadiaphyseal region of the distal fourth

finger with deep endosteal scalloping (arrow). There is associated

pathological fracture.

Osteochondroma

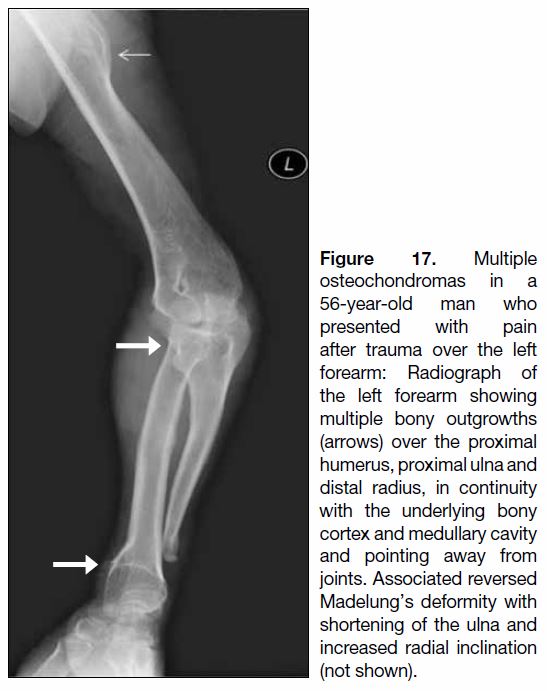

Osteochondroma is the most common bone tumour.

Around one in ten occur in the small bones of the hands

and feet.[28] It comprises cortical and medullary bone

with overlying hyaline cap, often asymptomatic and

an incidental finding on radiographs. Localised pain

may be present due to irritation of adjacent structures.

Radiographically (Figure 17), osteochondromas

are seen as a bony exostosis continuous with the

underlying parent bone cortex and medullary cavity

and pointing away from a joint. There are two forms of

osteochondromas radiographically, namely sessile and

pedunculated. Osseous continuity in the sessile type of

osteochondroma may be difficult to see on radiographs.

Multiple osteochondromas in the hand and wrist region

raises concern for underlying hereditary multiple

exostosis.

Figure 17. Multiple

osteochondromas in a

56-year-old man who

presented with pain

after trauma over the left

forearm: Radiograph of

the left forearm showing

multiple bony outgrowths

(arrows) over the proximal

humerus, proximal ulna and

distal radius, in continuity

with the underlying bony

cortex and medullary cavity

and pointing away from

joints. Associated reversed

Madelung’s deformity with

shortening of the ulna and

increased radial inclination

(not shown).

Nora’s Lesion

Nora’s lesions, also known as bizarre parosteal

osteochondromatous proliferations, are benign surface

lesions of the small tubular bones of the hand. Nora’s

lesions typically involve the metaphysis or diaphysis

of the phalanges and metacarpals. They are thought to be due to reactive heterotopic mineralisation arising

from the periosteal aspect of an intact cortex, without

involvement of the medullary canal.[28] Nora’s lesions

occurring under the nail bed are called subungual

exostosis. Radiographically (Figure 18), Nora’s lesions

are seen as broad-based ossified juxtacortical lesions,

without definite cortical or medullary continuation.[32]

Periosteal reaction is usually absent. Radiographs

alone are sufficient for diagnosis as they have a typical

radiographic appearance.[28] Computed tomography

(Figure 19) or MRI (Figure 20) scans are reserved for

cases with inconclusive radiographic findings as they better demonstrate the relationship with underlying

bone. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice but the

recurrence rate is high at 50% to 55%.[33]

Figure 18. Nora’s lesion in a 41-year-old

woman who presented with left

little finger mass: Frontal and lateral

radiographs of the left fifth finger show

an ossified lesion over the dorsal

aspect of the fifth proximal phalanx

as indicated by the metallic marker,

closely related to the underlying cortex.

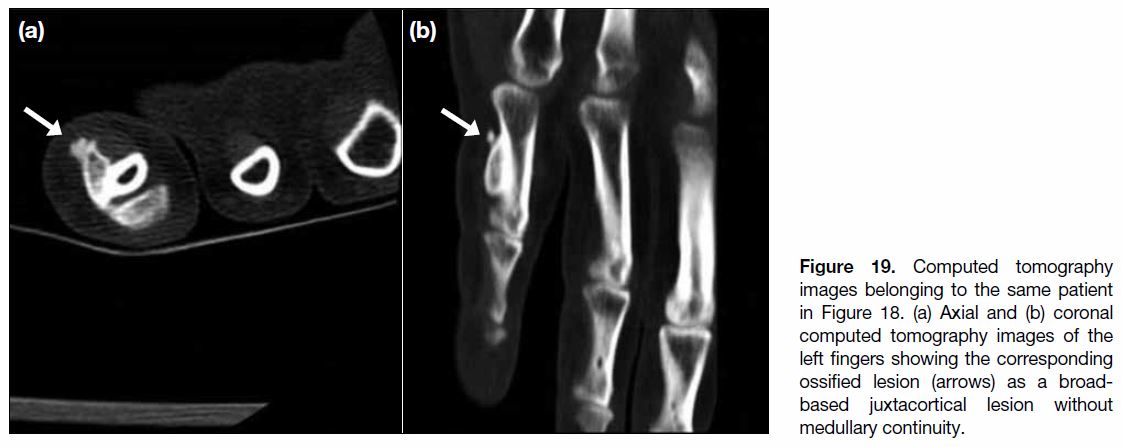

Figure 19. Computed tomography

images belonging to the same patient

in Figure 18. (a) Axial and (b) coronal

computed tomography images of the

left fingers showing the corresponding

ossified lesion (arrows) as a broad-based

juxtacortical lesion without

medullary continuity.

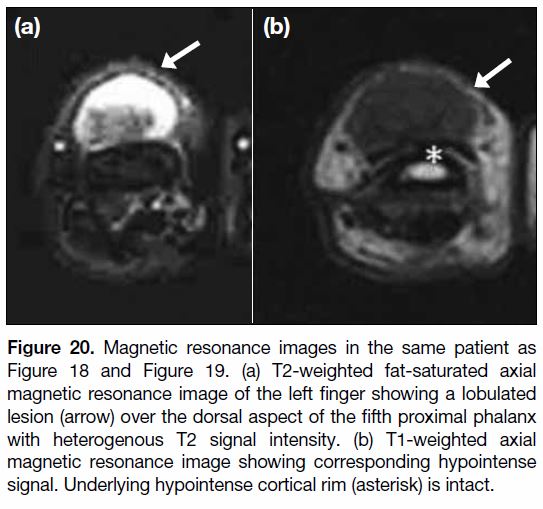

Figure 20. Magnetic resonance images in the same patient as

Figure 18 and Figure 19. (a) T2-weighted fat-saturated axial

magnetic resonance image of the left finger showing a lobulated

lesion (arrow) over the dorsal aspect of the fifth proximal phalanx

with heterogenous T2 signal intensity. (b) T1-weighted axial

magnetic resonance image showing corresponding hypointense

signal. Underlying hypointense cortical rim (asterisk) is intact.

CONCLUSION

A variety of lesions may present in the hand and

wrist region. Imaging plays an important role in their

characterisation and diagnosis. Plain radiographs remain

the first imaging of choice for patients with any complaints

in the hand and wrist region, but has a limited role in soft

tissue lesions. To investigate a soft tissue mass or swelling,

ultrasonography can be initially employed to confirm the presence of a mass lesion and differentiate cystic from

non-cystic masses. Ultrasonography can also provide

useful information about anatomical location, thereby

narrowing the differential diagnoses. In general, MRI is

the preferred modality to further characterise non-cystic

masses. For osseous lesions, computed tomography and

MRI are reserved for complex cases and/or when there

is any doubt. Knowledge of their characteristic imaging

features along with relevant clinical findings will enable

the radiologist to make a correct diagnosis and avoid the

need for invasive procedures. Some lesions have very

similar imaging characteristics and biopsy is required

to establish the diagnosis. Imaging guided percutaneous

biopsy is commonly performed for pathological analysis.

In particular, ultrasonography and computed tomography

are often used for guidance. Overall, imaging plays an

important role in the diagnostic workup of hand lesions.

It also serves as a guide for subsequent management or

surgical planning for clinicians.

REFERENCES

1. Thornburg LE. Ganglions of the hand and wrist. J Am Acad Orthop

Surg. 1999;7:231-8. Crossref

2. Soren A. Pathogenesis and treatment of ganglion. Clin Orthop Relat

Res. 1966;48:173-9. Crossref

3. Vanhoenacker FM, Eyselbergs M, Van Hul E, Van Dyck P,

De Schepper AM. Pseudotumoural soft tissue lesions of the hand

and wrist: a pictorial review. Insights Imaging. 2011;2:319-33. Crossref

4. Ergun T, Lakadamyali H, Derincek A, Tarhan NC, Ozturk A.

Magnetic resonance imaging in the visualization of benign tumors

and tumor-like lesions of hand and wrist. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol.

2010;39:1-16. Crossref

5. Hong SH, Chung HW, Choi JY, Koh YH, Choi JA, Kang HS. MRI

findings of subcutaneous epidermal cysts: emphasis on the presence of rupture. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:961-6. Crossref

6. Murphey MD, Rhee JH, Lewis RB, Fanburg-Smith JC, Flemming

DJ, Walker EA. Pigmented villonodular synovitis: radiologic-pathologic

correlation. Radiographics. 2008;28:1493-518. Crossref

7. Fletcher CD, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PC, Mertens F, editors.

World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology

and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. IARC Press:

Lyon; 2013.

8. Peh WC, Shek TW, Ip WY. Growing wrist mass. Ann Rheum Dis.

2001;60:550-3. Crossref

9. Wang C, Song RR, Kuang PD, Wang LH, Zhang MM. Giant cell

tumor of the tendon sheath: Magnetic resonance imaging findings

in 38 patients. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:4459-62. Crossref

10. Van Geertruyden J, Lorea P, Goldschmidt D, de Fontaine S,

Schuind F, Kinnen L, et al. Glomus tumours of the hand. A

retrospective study of 51 cases. J Hand Surg Br. 1996;21:257-60. Crossref

11. Baek HJ, Lee SJ, Cho KH, Choo HJ, Lee SM, Lee YH, et.al.

Subungual tumors: clinicopathological correlation with US and

MR imaging findings. Radiographics. 2010;30:1621-36. Crossref

12. Theumann NH, Goettmann S, Le Viet D, Resnick D, Chung CB,

Bittoun J, et al. Recurrent glomus tumors of fingertips: MR imaging

evaluation. Radiology.2002;223:143-51. Crossref

13. Chung EB, Enzinger FM. Fibroma of tendon sheath. Cancer.

1979;44:1945-54. Crossref

14. Dinauer PA, Brixey CJ, Moncur JT, Fanburg-Smith JC,

Murphey MD. Pathologic and MR imaging features of benign

fibrous soft-tissue tumors in adults. Radiographics. 2007;27:173-87. Crossref

15. Fox MG, Kransdorf MJ, Bancroft LW, Peterson JJ, Flemming DJ.

MR imaging of fibroma of the tendon sheath. AJR Am J

Roentgenol. 2003;180:1449-53. Crossref

16. Vassallo P. Diagnostic imaging of mass lesions in the hand. The

Synapse. 2015;14;29-31.

17. Murphey MD, Ruble CM, Tyszko SM, Zbojniewicz AM,

Potter BK, Miettinen M. From the archives of the AFIP:

musculoskeletal fibromatoses: radiologic-pathologic correlation.

Radiographics. 2009;29:2143-73. Crossref

18. Morris G, Jacobson JA, Kalume Brigido M, Gaetke-Udager K,

Yablon CM, Dong Q. Ultrasound features of palmar fibromatosis

or Dupuytren contracture. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38:387-92. Crossref

19. Kransdorf MJ. Benign soft-tissue tumors in a large referral

population: distribution of specific diagnoses by age, sex, and

location. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:395-402. Crossref

20. Paunipagar BK, Griffith JF, Rasalkar DD, Chow LT, Kumta SM,

Ahuja A. Ultrasound features of deep-seated lipomas. Insights

Imaging. 2010;1:149-53. Crossref

21. Gaskin CM, Helms CA. Lipomas, lipoma variants, and well-differentiated

liposarcomas (atypical lipomas): results of MRI

evaluations of 126 consecutive fatty masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

2004;182:733-9. Crossref

22. Marom EM, Helms CA. Fibrolipomatous hamartoma: pathognomonic

on MR imaging. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28:260-4. Crossref

23. The J. Ultrasound of soft tissue masses of the hand. J Ultrason.

2012;12:381-401. Crossref

24. Abreu E, Aubert S, Wavreille G, Gheno R, Canella C, Cotton A.

Peripheral tumor and tumor-like neurogenic lesions. Eur J Radiol.

2013;82:38-50. Crossref

25. Flors L, Leiva-Salinas C, Maged IM, Norton PT, Matsumoto AH,

Angle JF, et.al. MR imaging of soft-tissue vascular malformations:

diagnosis, classification, and therapy follow-up. Radiographics.

2011;31:1321-40. Crossref

26. Madani H, Farrant J, Chhaya N, Anwar I, Marmery H, Platts A, et al.

Peripheral limb vascular malformations: an update of appropriate

imaging and treatment options of a challenging condition. Br J Radiol. 2015;88:20140406. Crossref

27. Millender LH, Nalebuff EA, Kasdon E. Aneurysms and thromboses

of the ulnar artery in the hand. Arch Surg. 1972;105:686-90. Crossref

28. Douis H, Saifuddin A. The imaging of cartilaginous bone tumours.

I. Benign lesions. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41:1195-212. Crossref

29. Melamud K, Drapé JL, Hayashi D, Roemer FW, Zentner J,

Guermazi A. Diagnostic imaging of benign and malignant osseous

tumors of the fingers. Radiographics. 2014;34:1954-67. Crossref

30. Larbi A, Viala P, Omoumi P, Lecouvet F, Malghem J, Cyteval C,

et al. Cartilaginous tumours and calcified lesions of the hand: a

pictorial review. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2013;94:395-409. Crossref

31. Herget GW, Strohm P, Rottenburger C, Kontny U, Krauß T,

Bohm J, et al. Insights into enchondroma, enchondromatosis and

the risk of secondary chondrosarcoma. Review of the literature

with an emphasis on the clinical behaviour, radiology, malignant

transformation and the follow up. Neoplasma. 2014;61:365-78. Crossref

32. Dhondt E, Oudenhoven L, Khan S, Kroon HM, Hogendoorn PC,

Nieborg A, et al. Nora’s lesion, a distinct radiological entity.

Skeletal Radiol. 2006;35:497-502. Crossref

33. Joseph J, Ritchie D, MacDuff E, Mahendra A. Bizarre parosteal

osteochondromatous proliferation: a locally aggressive benign

tumor. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:2019-27. Crossref

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| v23n4_Benign.pdf | 516.8 KB |