Early Local Community Data on Safety and Efficacy of Fruquintinib in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Hong Kong J Radiol 2024 Sep;27(3):e147-55 | Epub 16 September 2024

Early Local Community Data on Safety and Efficacy of Fruquintinib in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

HK So1, TTS Lau1, NSM Wong2, M Tong3, JJ Huang3, CY Shum1

1 Department of Oncology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Clinical Oncology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Cluster Quality and Safety Division, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr HK So, Department of Oncology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: hk.so@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 28 April 2024; Accepted: 2 July 2024.

Contributors: HKS, NSMW, TTSL and CYS designed the study. HKS, NSMW, MT and JJH acquired the data. HKS analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. NSMW, TTSL and CYS critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This research was approved by the Central Institutional Review Board of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: CIRB-2023-006-2). Informed patient consent was waived by the Board due to the retrospective nature of the research and the use of anonymised data.

Abstract

Introduction

Fruquintinib, a selective inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1, -2, and -3 tyrosine

kinases, is indicated for late-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). This retrospective study aimed to review the safety and efficacy of fruquintinib in the Hong Kong population.

Methods

Patients with mCRC who had failed at least two standard chemotherapy regimens were treated with

fruquintinib at two tertiary centres in Hong Kong between December 2021 and July 2023. We reported overall survival, event-free survival (EFS), disease control rate, and toxicity. EFS was defined as the time from starting treatment to an event, which could be disease progression, discontinuation of treatment for any reason, or death.

Results

A total of 26 mCRC patients were treated with fruquintinib. The median overall survival and median EFS

were 8.9 months and 4.2 months, respectively. Among the 22 patients who experienced an event, 15 (57.7%) had

disease progression, six (23.1%) discontinued treatment for any reason, and one (3.8%) died. The disease control

rate was 38.5%, including two (7.7%) patients with partial response and eight (30.8%) patients with stable disease.

Grade ≥3 adverse reactions occurred in 69.2% of patients, the most common of which were hypertension (53.8%),

hand-foot syndrome (19.2%), and diarrhoea (11.5%). There were no treatment-related deaths.

Conclusion

Fruquintinib demonstrated reasonable clinical efficacy and a manageable safety profile, consistent with

the findings of international clinical studies. It is a valid option for later-line mCRC patients.

Key Words: Carcinoembryonic antigen; ErbB receptors; Hand-foot syndrome; Vascular endothelial growth factor A

中文摘要

使用呋喹替尼治療轉移性大腸癌的安全性及有效性的早期本地社區數據

蘇衍錕、劉芷珊、黃善敏、唐雯、黃嘉杰、岑翠瑜

引言

呋喹替尼是一種血管內皮生長因子受體(VEGFR)-1、-2及-3酪胺酸激酶選擇性抑制劑,適用於轉移性大腸癌的後期治療。本回顧性研究旨在調查於香港人口使用呋喹替尼的安全性及有效性。

方法

經歷最少兩次標準化療方案失敗的轉移性大腸癌患者於2021年12月至2023年7月期間在香港兩所三級醫療機構接受呋喹替尼治療。我們報告整體存活期、無事件存活期、疾病控制率及毒性數據。無事件存活期的定義為開始治療起計至有事件發生的時間,可能包括病情惡化、因任何原因導致停止治療或死亡。

結果

共有26名轉移性大腸癌患者接受呋喹替尼治療。整體存活期中位數及無事件存活期中位數分別為8.9個月及4.2個月。在22名有事件發生的患者當中,15名(57.7%)病情惡化,6名(23.1%)因任何原因導致停止治療,1名(3.8%)死亡。疾病控制率為38.5%,包括兩名(7.7%)部分反應患者及8名(30.8%)反應穩定患者。共有69.2%患者出現三級或以上不良反應,最常見為高血壓(53.8%)、手足症候群(19.2%)及腹瀉(11.5%)。本研究沒有與治療有關的死亡個案。

結論

呋喹替尼具有合理的臨床有效性及易於管理的安全狀況,與國際臨床研究結果一致,是後期轉移性大腸癌患者的有效選項。

INTRODUCTION

Globally, colorectal cancer is the third most common

type of cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related

deaths.[1] In Hong Kong, colorectal cancer was not

only the second most common cancer but also the second

most common cause of cancer-related deaths in 2020.[2]

The primary treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer

(mCRC) is chemotherapy, often supplemented by

targeted therapy and, in certain cases, immunotherapy

for patients with mismatch repair deficient tumours. For

chemotherapy, standard chemotherapy regimens include

5-fluorouracil (or its oral prodrug capecitabine) plus either

oxaliplatin or irinotecan, or both.[3] [4] Targeted therapy

agents include bevacizumab and aflibercept, which

target the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)

pathway; and cetuximab and panitumumab, which target

the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway.[3] [4]

Later-line treatment regimens include trifluridine-tipiracil[5]

and regorafenib.[6] These two agents offer only

modest improvements in overall survival (OS) and

progression-free survival. However, even after failure on

multiple different treatment strategies, patients may still maintain good performance status. This underscores the

necessity for more safe and effective treatment options.

Fruquintinib is a selective inhibitor of vascular

endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR)-1, -2, and -3

tyrosine kinases.[7] In the phase III FRESCO randomised

clinical trial (Fruquintinib Efficacy and Safety in 3+ Line

Colorectal Cancer Patients), fruquintinib significantly

improved the median overall survival (mOS) compared

with that of the placebo group (9.3 months [95%

confidence interval (CI) = 8.2-10.5] vs. 6.6 months

[95% CI = 5.9-8.1]) in Chinese patients with mCRC

who progressed after at least two prior chemotherapy

regimens (i.e., third- or later-line use).[8] It was approved

in Mainland China in 2018 and was granted a fast-track

designation by the US Food and Drug Administration in

June 2020 for the above indication.[9] Another recent phase

III FRESCO-2 randomised clinical trial also showed

significant improvement in mOS with fruquintinib

compared with placebo (7.4 months [95% CI = 6.7-8.2] vs. 4.8 months [95% CI = 4.0-5.8]).[10] Fruquintinib

received its approval from the US Food and Drug

Administration on 8 November 2023, for adult patients with mCRC who had previously received 5-fluorouracil,

oxaliplatin and irinotecan-based chemotherapy, anti-VEGF therapy, and anti-EGFR therapy (if the tumour was RAS-wild type).[11]

The FRESCO trial recruited 416 Chinese patients from

Mainland China, where fruquintinib was developed.[8]

On the other hand, the FRESCO-2 trial included

patients from North America, Europe, Australia and

Japan, but Japanese patients comprised <10% of the

trial population.[10] The FRESCO trial excluded patients

who had been previously exposed to regorafenib,[8]

while patients who progressed on or were intolerant

to trifluridine-tipiracil or regorafenib could enter the

FRESCO-2 trial.[10] Hong Kong was not a study site in

either trial, and local experience in the use of fruquintinib

was scarce.

This study aimed to analyse the safety and efficacy

of fruquintinib in mCRC patients. To the best of our

knowledge, this is the first retrospective study of

fruquintinib in public healthcare setting in the local

population.

METHODS

Data Collection and Participants

Clinical data from 26 patients who received fruquintinib

between 31 December 2021 and 22 July 2023 were

retrospectively reviewed and collected from the

institutional databases of two tertiary centres in Hong

Kong, namely, Princess Margaret Hospital and Tuen

Mun Hospital. The inclusion criteria for fruquintinib

use were modified from the FRESCO[8] and FRESCO-2[10]

trials, which were as follows: (1) age ≥18 years; (2)

an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)

performance status score of 0 to 1; (3) histologically

confirmed mCRC; (4) failure (progressive disease or

intolerance) on at least two standard chemotherapy

regimens using fluoropyrimidine, irinotecan, oxaliplatin,

anti-VEGF antibodies (bevacizumab and aflibercept),

or anti-EGFR antibodies (cetuximab or panitumumab);

(5) measurable disease by Response Evaluation Criteria

in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1; (6) adequate

bone marrow reserve (absolute neutrophil count ≥1.5

× 109/L, platelet count ≥100 × 109/L, and haemoglobin level ≥9.0 g/dL); (7) renal function (serum creatinine

level ≤1.5 × upper limit of normal [ULN] or creatinine

clearance ≥60 mL/min; urine dipstick protein of ≤1+ or

24-hour urine protein level <1.0 g/24 h); and (8) liver

function (serum total bilirubin level ≤1.5 × ULN; alanine

aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase level ≤2.5 × ULN in subjects without hepatic metastases; and

alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase

level ≤5 × ULN in subjects with hepatic metastases).

There were no exclusion criteria involving prior use of

trifluridine-tipiracil or regorafenib.

Study Design

This was a local, single-arm, retrospective analysis of patients with mCRC conducted at two tertiary centres

in Hong Kong. These patients had either progressed

or shown intolerance after receiving at least two lines

of chemotherapy. The included patients underwent

repeated 28-day treatment cycles of fruquintinib, with

a schedule of 3 weeks on the medication (5 mg oral

daily) followed by a 1-week break. This treatment

cycle was continued until disease progression, death,

occurrence of unacceptable toxicity, or discontinuation

by the physician. Dose reduction was allowed to manage

treatment-related adverse effects and followed the

protocol of the FRESCO trial.[8]

Clinical Assessment Outcomes and Endpoints

The primary endpoint was OS, defined as the time from

the start of treatment using fruquintinib to death from

any cause. Tumour response assessment was performed

at intervals subject to the availability of imaging and

physician discretion, and response was defined by

RECIST version 1.1. The secondary endpoints were

event-free survival (EFS) [defined as the time from

starting treatment to an event, which could be disease

progression defined as the first documentation of disease

progression assessed by the investigator according to

RECIST version 1.1, discontinuation of treatment for

any reason, or death], duration of treatment (defined as

the time from starting treatment to last study treatment

dose), objective response rate (defined as confirmed

complete or partial response), disease control rate

(defined as the sum of the complete response, partial

response and stable disease rates), and carcinoembryonic

antigen (CEA) response. EFS was selected instead of

progression-free survival because the imaging intervals

in real-world settings vary. In heavily pretreated patients,

quality of life (QoL) is important, and discontinuation of

treatment for any reason can also indicate the tolerability

of a drug. For CEA response, a definition modified from

the RECIST criteria was used to evaluate treatment

response, and responses were classified into three groups,

namely, CEA-RD (responsive disease), CEA-SD (stable

disease), and CEA-PD (progressive disease).[12] [13] CEA-RD

was defined as a decrease of >30% from the original level; CEA-PD was defined as an increase of >20% from

the original level.[12] [13] A change in the CEA level that

did not meet the criteria for CEA-RD and CEA-PD was

defined as CEA-SD.[12] [13]

Adverse events (AEs) were recorded throughout the

study from the start of treatment to the end of the study

period or the start of the next line of treatment. They

were graded according to the National Cancer Institute

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

version 5.0.[14]

Statistical Analysis

For OS and EFS, the Kaplan-Meier method was used

to estimate the median survival time and 95% CI.

Relationships between individual patient characteristics

and OS or EFS were analysed using the Cox proportional

hazards model to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95%

CIs. All analyses were performed using commercial

software SPSS (Windows version 28.0; IBM Corp,

Armonk [NY], US). A p value of < 0.05 was considered

statistically significant.

RESULTS

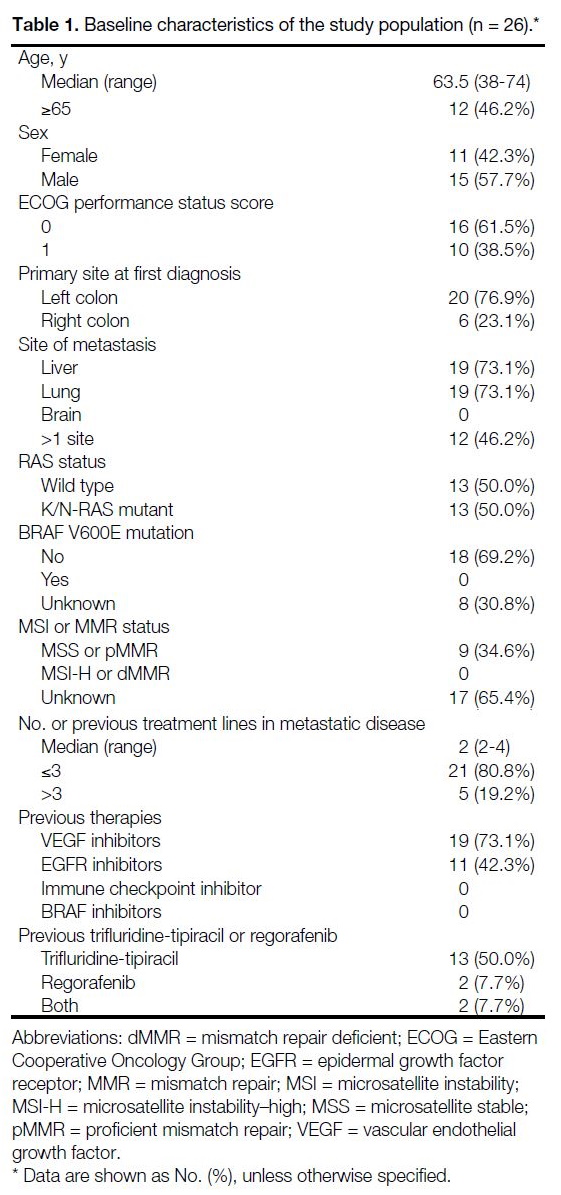

The baseline demographics and disease characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study population (n = 26).

Efficacy

Survival Outcomes and Duration of Treatment

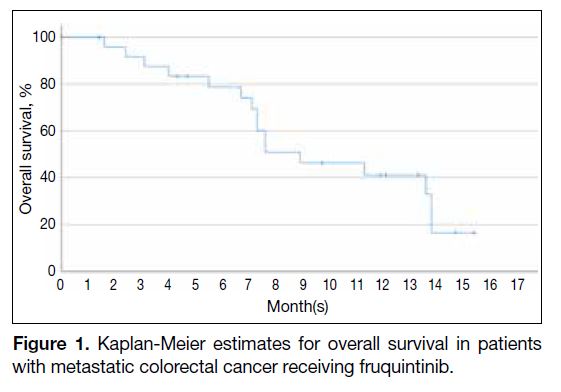

The median duration of treatment was 4.3 months (range, 0.6-15.4) and the median number of treatment cycles

was 3 (range, 1-17). The median follow-up time was 7.3

months. The mOS was 8.9 months (95% CI = 4.5-13.3).

The Kaplan-Meier plot for OS is shown in Figure 1. The

proportion of patients still alive at 6 months was 78.7%

and that at 12 months was 41.2%.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier estimates for overall survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving fruquintinib.

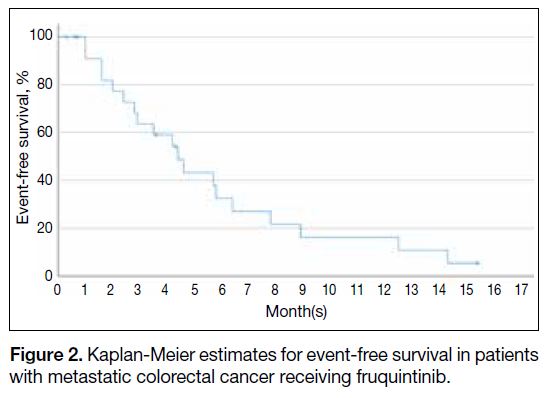

The median EFS was 4.2 months (95% CI = 2.5-5.9).

Among the 22 of 26 patients who experienced an

event, 15 (57.7%) had disease progression, six (23.1%)

discontinued treatment for any reason, and one (3.8%)

died. The Kaplan-Meier plot for EFS is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier estimates for event-free survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving fruquintinib.

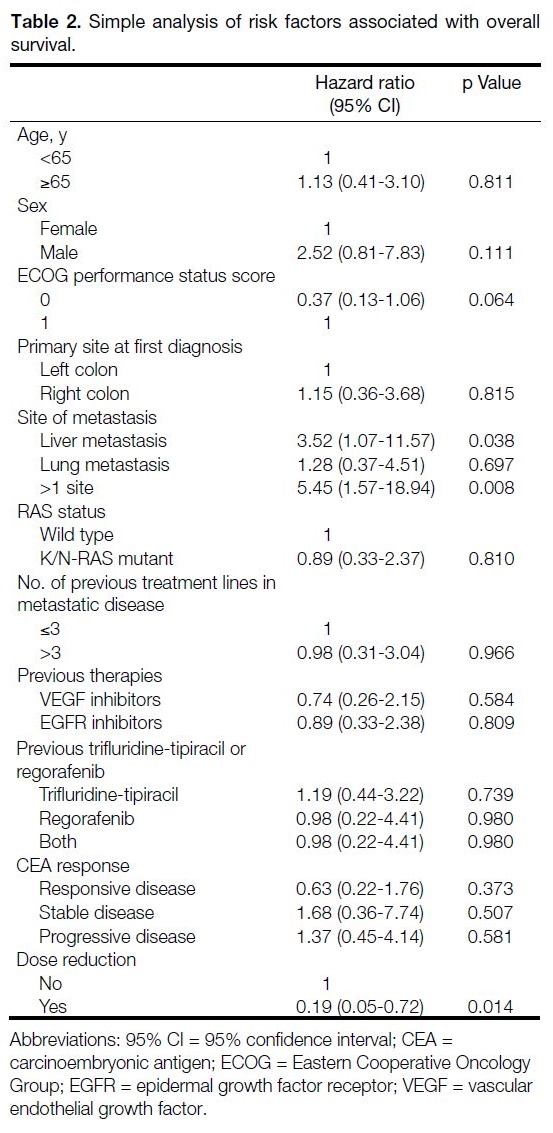

Subgroup analyses of OS and EFS were carried out

with a Cox proportional hazards model (simple and

multivariable), but only a few clinical, tumour, or

treatment factors exhibited a statistically significant

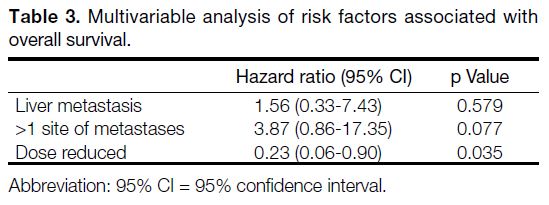

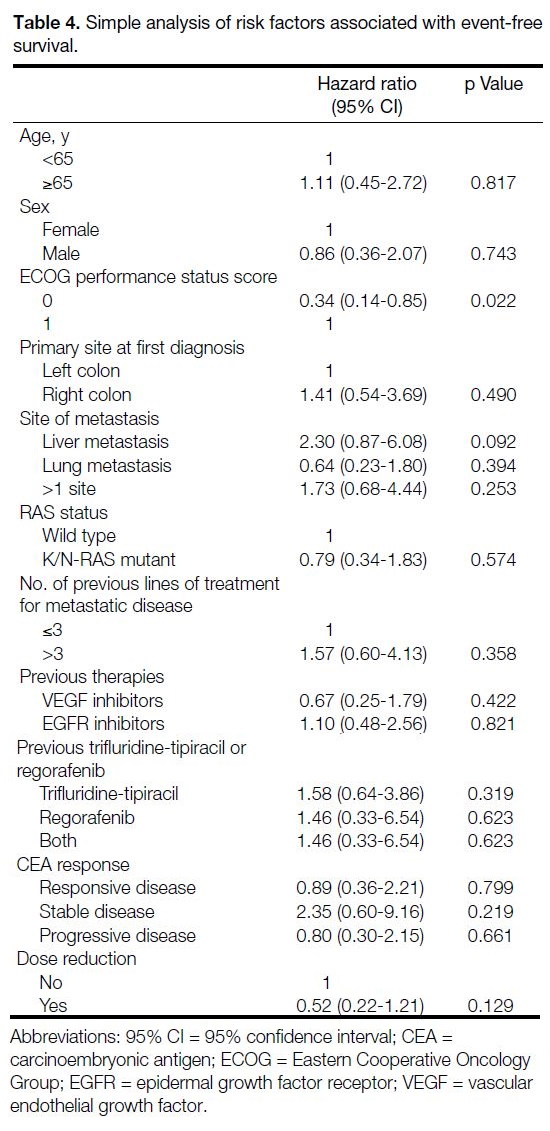

correlation (Tables 2, 3 and 4). Simple analysis also revealed

that OS was worse for patients with liver metastasis and

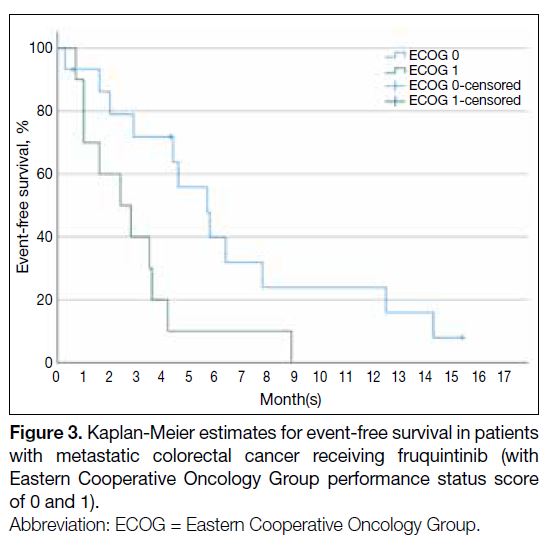

with multiple sites of metastasis (Table 2). Patients with an ECOG performance status score of 0 had better EFS

(HR = 0.34; 95% CI = 0.14-0.85) [Table 4 and Figure 3].

Previous use of trifluridine-tipiracil, regorafenib, or both

did not significantly affect OS or EFS (Tables 2, 3 and 4).

Table 2. Simple analysis of risk factors associated with overall survival.

Table 3. Multivariable analysis of risk factors associated with overall survival.

Table 4. Simple analysis of risk factors associated with event-free survival.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier estimates for event-free survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving fruquintinib (with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score of 0 and 1).

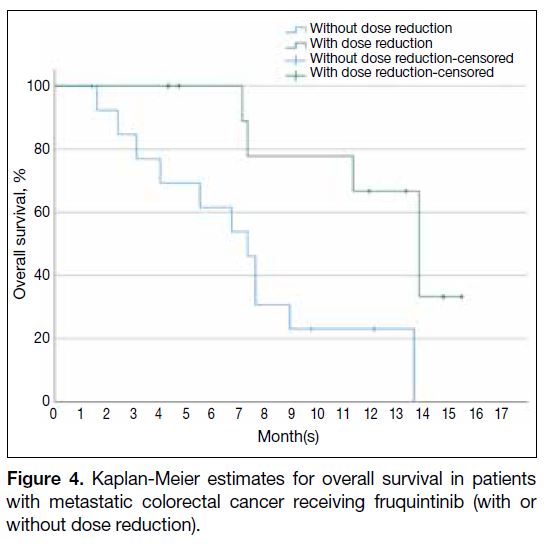

The starting dose of fruquintinib was 5 mg daily (3 weeks on, 1 week off). 11 patients had their dose reduced, with

5 patients (19.2%) being reduced to 4 mg dailiy and 6 patients (23.1%) being reduced to 3 mg dailiy. Dose

reduction of fruquintinib was associated with better OS

(HR = 0.19, 95% CI = 0.05-0.72; p = 0.014) [Table 2 and Figure 4], but not in EFS (HR = 0.52, 95% CI = 0.22-1.21; p = 0.129) [Table 4].

Figure 4. Kaplan-Meier estimates for overall survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving fruquintinib (with or without dose reduction).

Radiological Response

In patients treated with fruquintinib, the disease control rate was 38.5% (10 of 26 patients), which included two

(7.7%) patients with partial response and eight patients

(30.8%) with stable disease. There was no patient with

complete response.

Carcinoembryonic Antigen Response

Regarding serum CEA responses, the differences in

OS and EFS were not statistically significant between

patients with CEA-RD, CEA-SD and CEA-PD.

Numerically, patients with CEA-RD had better OS and

EFS than patients with CEA-PD (Tables 2, 3 and 4).

Adverse Events

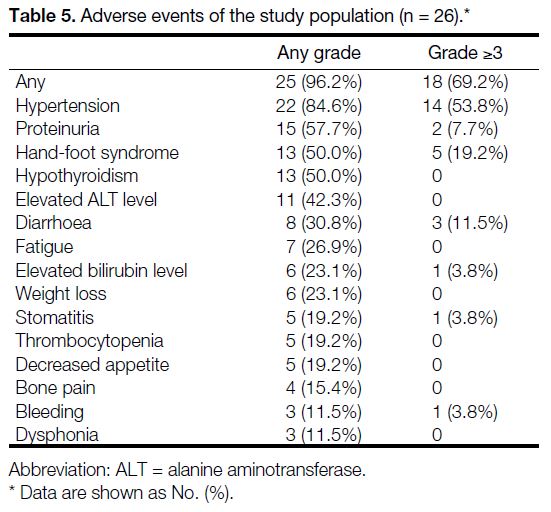

Twenty-five of 26 patients (96.2%) had at least one AE

of any grade (Table 5). The most frequently reported AEs of any grade were hypertension (84.6%), proteinuria

(57.7%), hand-foot syndrome (HFS) [50%], and

hypothyroidism (50%). Severe AEs (grade ≥3) occurred

in 18 patients (69.2%), with the most common being

hypertension (53.8%), HFS (19.2%), and diarrhoea

(11.5%) [Table 5]. There were no treatment-related

deaths in the study population.

Table 5. Adverse events of the study population (n = 26).

Six of 26 patients (23.1%) discontinued fruquintinib due to treatment-related AEs. The most frequent AE that led

to treatment discontinuation was HFS in two patients (7.7%). Treatment interruption due to AEs occurred

in five patients (19.2%), and the most common AE

associated with treatment interruption was hypertension

in two patients (7.7%). Dose reduction due to AEs

occurred in 11 patients (42.3%). The most frequent

AEs leading to dose reductions were HFS (11.5%),

proteinuria (11.5%), and diarrhoea (7.7%).

DISCUSSION

This retrospective study investigated the local

population treated with fruquintinib at two tertiary institutions in Hong Kong, which included patients who

had experienced disease progression following at least

two lines of chemotherapy. This study did not have a

placebo arm; the analysis of the results focuses on early

experience of safety and efficacy in our locality.

Efficacy

In this study, the mOS was 8.9 months and the median

EFS was 4.2 months, with a disease control rate of 38.5%.

In Hong Kong, third-line or beyond monotherapy options

for mCRC include trifluridine-tipiracil and regorafenib.

In the RECOURSE trial (trifluridine-tipiracil vs. placebo

in patients with previously treated mCRC), the treatment

group had an mOS of 7.1 months and a disease control

rate of 44%.[5] In the CONCUR trial (regorafenib vs.

placebo in Asian patients with previously treated

mCRC), the treatment group had an mOS of 8.8 months

and a disease control rate of 51%.[6] Our data suggest

that fruquintinib is a feasible monotherapy option in the

third line and beyond setting for mCRC patients in Hong

Kong.

OS and EFS analyses did not reveal any statistically

significant differences in most of the subgroups (Tables 2, 3 and 4), although OS was shown to worsen when

patients had liver metastasis or more than one site of

metastasis (Table 2). EFS was shown to be related to

ECOG performance status score (Table 4). There was

no statistically significant correlation between CEA

response and OS or EFS (Tables 2, 3 and 4), although OS

tended to improve in patients with CEA-RD and tended

to worsen in patients with CEA-PD.

In terms of the radiological and CEA (tumour marker)

response, there were more patients with CEA-RD than

there were with an objective response. This could be due

to less intensive imaging schedules in public hospital

settings, such that metabolic or relatively short-lived

treatment responses could not be captured radiologically.

Further study is needed to confirm the correlation

between CEA response and survival, and studying

the CEA response could help determine whether it

can supplement the suboptimal scanning schedule in

assessing the treatment response.

Adverse Events

The incidence of AEs and serious AEs was considerably

high in the study population. The most frequently reported

grade ≥3 AEs were hypertension, HFS, and diarrhoea

(Table 5). These AEs were manageable by supportive

measures and dose modification. The discontinuation of

fruquintinib in this study was 26.9%, whereas the rate

in FRESCO and FRESCO-2 were 15.1%[8] and 20%,[10]

respectively. Further QoL analysis would be valuable to

correlate the relatively high incidence of AEs and their

impact on patient’s QoL.

Baseline hypertension was a strong risk factor for high-grade hypertensive toxicity. Among the 14 patients who

experienced grade ≥3 hypertension, all had preexisting

hypertension at baseline. The baseline hypertension rate

(88.4%, n = 23) was relatively high when compared

to that of the general population (57.4% in the 65-84

age-group).[15] The odds ratio associated with grade

≥3 hypertension was 7.00 for patients with baseline

hypertension of any grade (95% CI = 0.34-144.06; p = 0.20). Of those patients with baseline hypertension,

only eight (34.8%) received intervention. Home blood

pressure monitoring was started or ensured in seven

patients, while antihypertensive therapy was started or

titrated only in one patient. Of the eight patients who

underwent intervention, seven (87.5%) still developed

grade ≥3 hypertension. These findings suggested that

more aggressive intervention by managing oncologists

is needed for patients with baseline hypertension.

According to the evidence from regorafenib, which is

also a VEGFR inhibitor, when encountering grade 2

hypertension, treating physicians can consider starting

a single antihypertensive agent (such as an angiotensin-converting

enzyme inhibitor).[16] For grade 3 hypertension,

an additional agent (such as a beta blocker) should be

considered, and if it remains refractory, a third agent

(such as a calcium channel blocker) may be added. Diuretics should be avoided because diarrhoea is also a common side-effect of fruquintinib, which may cause dehydration.

Another important adverse reaction was HFS. In HFS

management, preventive measures include reducing skin

friction, reducing exposure to heat, using skin barriers

and early identification of skin abrasions.[17] The use of

urea-based cream in combination with sorafenib (also

a VEGFR inhibitor) has been shown to reduce the

incidence of HFS.[18] Other commonly used measures

include analgesics, topical anaesthetics, topical high-potency

corticosteroids, keratolytic, and emollients.[17] If

the above supportive measures are not able to improve

tolerance, physicians can consider reducing the dose

according to the drug’s prescription information.

A total of 99% of the patients experienced any grade of AE in the fruquintinib (FRESCO-2) trial,[10] 97% in the

regorafenib (CONCUR) trial[6] and 98% in the trifluridinetipiracil

(RECOURSE) trial,[5] with 63%, 54%, and 69%

of patients experiencing grade ≥3 AEs, respectively. For

specific grade ≥3 AEs, we compared the same class of

drugs (i.e., fruquintinib vs. regorafenib), and the two drugs

had similar severe AE profiles. Compared with drugs of a

different class (i.e., fruquintinib vs. trifluridine-tipiracil),

the toxicity profiles of these agents clearly differed, with

the chemotherapy class (trifluridine-tipiracil) having

more haematological toxicity, as one would expect. The

most common severe AEs associated with trifluridine-tipiracil

were neutropenia (38%), leukopenia (21%), and

anaemia (18%).[5]

Patients in whom the dose was reduced had better OS

and tended to improve EFS. As the dose reduction was

mainly in response to toxicity, toxicity may be a predictor

of the VEGFR inhibitor treatment response. A similar

phenomenon was observed with anti-EGFR therapy, and

a worse skin reaction was proven to be associated with

a better response. In the OPUS study (untreated EGFR-expressing

advanced colorectal cancer, FOLFOX4 vs.

FOLFOX plus cetuximab),19 patients with grade 3 to 4

skin toxicity had a 66.7% response rate, while grade 1

patients and grade 0 patients had response rates of 42.2%

and 13%, respectively. In the EPIC study (The European

Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition,

second-line treatment after oxaliplatin-based therapy,

cetuximab plus irinotecan versus irinotecan),20 the

median survival was 5.8 months for grade 0 toxicities,

11.7 months for grade 1 to 2 toxicities, and 15.6 months

for grade 3 to 4 toxicities. However, further studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis in fruquintinib therapy.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this was a

retrospective study based only on data from two public

tertiary centres in Hong Kong. Second, the sample

size was small, and some subgroup analyses did not

show statistical significance. Third, QoL data were not

collected in this study.

CONCLUSION

Fruquintinib demonstrated reasonable clinical efficacy

and a manageable safety profile and is a valid option

for later-line mCRC patients. Hypertension is the

most common high-grade toxicity, and preexisting

hypertension is a strong risk factor. Proactive

management of hypertension is strongly advocated.

Prompt AE management can optimise its clinical utility,

and dose reduction did not compromise efficacy. Further

study of treatment sequence and patient QoL among the

approved third-line or beyond options is needed.

REFERENCES

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-49. Crossref

2. Hong Kong Cancer Registry, Hospital Authority. Top ten cancers. 2021. Available from: https://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/topten.html. Accessed 14 May 2024.

3. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Colon Cancer, version 3. 2023. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf. Accessed 23 Sep 2023.

4. Cervantes A, Adam R, Roselló S, Arnold D, Normanno N, Taïeb J, et al. Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023;34:10-32. Crossref

5. Mayer RJ, Van Cutsem E, Falcone A, Yoshino T, Garcia-Carbonero R, Mizunuma N, et al. Randomized trial of TAS-102 for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1909-19. Crossref

6. Li J, Qin S, Xu R, Yau TC, Ma B, Pan H, et al. Regorafenib plus

best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care in

Asian patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer

(CONCUR): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase

3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:619-29. Crossref

7. Cao J, Zhang J, Peng W, Chen Z, Fan S, Su W, et al. A phase I study

of safety and pharmacokinetics of fruquintinib, a novel selective

inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1, -2, and-3

tyrosine kinases in Chinese patients with advanced solid tumors.

Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;78:259-69. Crossref

8. Li J, Qin S, Xu RH, Shen L, Xu J, Bai Y, et al. Effect of fruquintinib

vs placebo on overall survival in patients with previously treated

metastatic colorectal cancer: the FRESCO randomized clinical trial.

JAMA. 2018;319:2486-96. Crossref

9. HUTCHMED. Chi-Med announces fruquintinib granted U.S. FDA fast track designation for metastatic colorectal cancer [Press Release]. 2020 June 18. Available from: https://www.hutch-med.com/fruquintinib-granted-us-fda-fast-track-designation-for-mcrc/. Accessed 2 Sep 2024.

10. Dasari A, Lonardi S, Garcia-Carbonero R, Elez E, Yoshino T, Sobrero A, et al. Fruquintinib versus placebo in patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer (FRESCO-2): an

international, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study.

Lancet. 2023;402:41-53. Crossref

11. United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves fruquintinib in refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. 2023 November 8. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-fruquintinib-refractory-metastatic-colorectal-cancer. Accessed 2 Sep 2024.

12. Su YT, Chen JW, Chang SC, Jiang JK, Huang SC. The clinical experience of the prognosis in opposite CEA and image change after therapy in stage IV colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2022;12:20075. Crossref

13. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228-47. Crossref

14. United States Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. 2017 November 27. Available from: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_5x7.pdf. Accessed 2 Sep 2024.

15. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Hypertension. May 2023. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/healthtopics/content/25/35390.html. Accessed 20 Jan 2024.

16. Krishnamoorthy SK, Relias V, Sebastian S, Jayaraman V, Saif MW. Management of regorafenib-related toxicities: a review. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2015;8:285-97. Crossref

17. Kwakman JJ, Elshot YS, Punt CJ, Koopman M. Management of cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced hand-foot syndrome. Oncol Rev. 2020;14:442. Crossref

18. Ren Z, Zhu K, Kang H, Lu M, Qu Z, Lu L, et al. Randomized

controlled trial of the prophylactic effect of urea-based cream

on sorafenib-associated hand-foot skin reactions in patients with

advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:894-900. Crossref

19. Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A, et al. Cetuximab plus

5-FU/FA/oxaliplatin (FOLFOX-4) versus FOLFOX-4 in the first-line

treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): OPUS, a

randomized phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(Suppl 18):4035. Crossref

20. Jonker DJ, Karapetis CS, Moore M, Zalcberg JR, Tu D, Berry S, et al.

editors. Randomized phase III trial of cetuximab monotherapy

plus best supportive care (BSC) versus BSC alone in patients with

pretreated metastatic epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)–positive colorectal carcinoma: a trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (NCIC CTG) and the

Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group (AGITG). In: Proc

Am Assoc Cancer Res; 2007.