Exploring the Power of Hybrid Intervention: Utility of an Angio-CT System in Interventional Radiology

PICTORIAL ESSAY

Hong Kong J Radiol 2025;28:Epub 10 December 2025

Exploring the Power of Hybrid Intervention: Utility of an Angio-CT System in Interventional Radiology

CL Wong1, KKF Fung2, HY Lo1, LH Yeung1, JC Ng1, KH Lee1, DHY Cho1

1 Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Radiology, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr CL Wong, Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: wcl094@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 9 October 2024; Accepted: 24 October 2024. This version may differ from the final version when published in an issue.

Contributors: All authors designed the study. CLW and DHYC acquired the data. All authors analysed the data. CLW and KKFF drafted the

manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Review Board of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: CIRB-2024-231-3). Informed patient consent was waived by the Board due to retrospective nature of the study.

Acknowledgement: None

INTRODUCTION

The use of cross-sectional imaging in interventional

radiology (IR) procedures is crucial for accurate target

identification, procedure planning, guidance, and

immediate therapy response monitoring.

Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT), integrated

into angiography systems with flat-panel detectors, has

been widely adopted for supplementary cross-sectional

imaging during IR procedures, in order to improve

procedural precision and safety.

Combined angiography-CT (angio-CT) systems integrate

a helical CT scanner and an angiography unit, placed on

the same rail with the same patient table. This allows

for seamless transition between CT and conventional

fluoroscopy/angiography, avoiding the need to move

the patient and its attendant risks. Besides achieving a

more efficient workflow, it also provides superior image

quality in terms of contrast resolution, noise, and artefact reduction, and a larger field of view compared to CBCT.[1]

In a study comparing the use of CBCT and angio-CT

for transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE), the overall

image quality of CT hepatic angiography in angio-CT

outperformed that of CBCT in identification of tumour

arterial feeders, reduction of streak and respiratory

artefacts, resulting in higher overall image quality.[2]

Through illustrative cases, we aim to demonstrate the

advantages of angio-CT in a wide range of vascular and

non-vascular interventions.

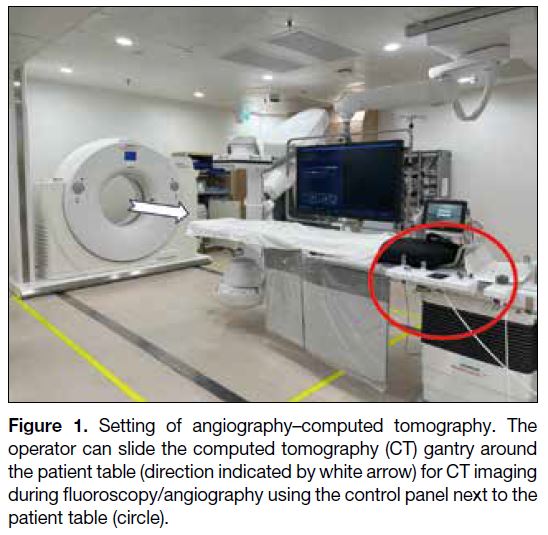

ANGIOGRAPHY–COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY SYSTEM

The angio-CT (Nexaris Angio-CT; Siemens, Tubingen,

Germany) which includes a C-arm angiography system

and a helical CT scanner installed on the same rail

system (Figure 1). During procedures, the patient is

positioned with the target organ as close as possible to

the CT gantry. While the patient is lying on the IR table

for fluoroscopy or angiography, the C-arm can be moved aside to allow the CT gantry to enclose the patient during

the procedure, enabling acquisition of three-dimensional

(3D) image data that can be processed and analysed

immediately at the workstation. Immediate fusion of

3D angiography and fluoroscopy allows the operator to

navigate to the target during IR procedures such as radio-embolisation

and TACE, where precision is crucial.

Figure 1. Setting of angiography–computed tomography. The

operator can slide the computed tomography (CT) gantry around

the patient table (direction indicated by white arrow) for CT imaging

during fluoroscopy/angiography using the control panel next to the

patient table (circle).

IMAGE ACQUISITION AND

INJECTION PROTOCOL CLINICAL

APPLICATIONS

Transarterial Chemoembolisation

Improving Visualisation of Small Hepatocellular

Carcinoma

Angio-CT with hepatic arteriography outperforms

diagnostic CT in terms of hepatocellular carcinoma

(HCC) visualisation.[1] [3] It can sometimes detect small

HCCs that are not conspicuous in magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) or digital subtraction angiography

(DSA),[4] as demonstrated in the case below.

A 59-year-old hepatitis B carrier with a history of

HCCs at segments 7/8 and 6 (Figure 2 a-c) treated with

microwave ablation. During follow-up, alpha-fetoprotein

level elevated up to 10 ng/mL. Contrast MRI of the liver

showed suspicious multifocal recurrence of HCCs and

the patient was referred for TACE. Angio-CT hepatic

arteriography demonstrated superior diagnostic power

compared to DSA and MRI in detection of subcentimeter HCC with faint arterial enhancement. All lesions

demonstrated lipiodol deposition on postprocedural

CT, with complete staining, a predictive factor for good

therapeutic response to TACE.[3] Alpha-fetoprotein level

in follow-up decreased to 7.9 ng/mL (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A 59-year-old patient. (a-c) Magnetic resonance imaging of the liver with gadoxetic

acid contrast in the arterial phase shows suspicious multifocal

subcentimeter recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma in segments 6, 7

and 8 (arrows). The arrow in (c) indicates a faint arterial enhancing

focus at segment 6 near the liver edge. (d) Right hepatic artery digital

subtraction angiography shows no tumour blush in the MRI detected

lesions. (e-g) Angio-CT with intra-arterial contrast injection into the

right hepatic artery shows multiple arterial-phase enhancing lesions

corresponding to the MRI-detected tumours as seen in (a) to (c)

[arrowheads]. Chemoembolisation was performed. (h-j) Immediate

post–transarterial chemoembolisation plain CT on the angio-CT

system shows lipiodol uptake in target lesions (dashed arrows).

All lesions demonstrated lipiodol deposition on the postprocedural

scan, with complete staining seen in (i) and (j).

Improving Visualisation of Extrahepatic Arterial

Supply

For HCC cases with extrahepatic supply, studies suggest

that Angio-CT arteriography offers superior diagnostic

capability compared to conventional triphasic CT liver

and DSA.[1] [4] Its use can increase sensitivity in detecting

and confirming parasitic supply, thereby guiding

additional treatment strategies.[3] [4]

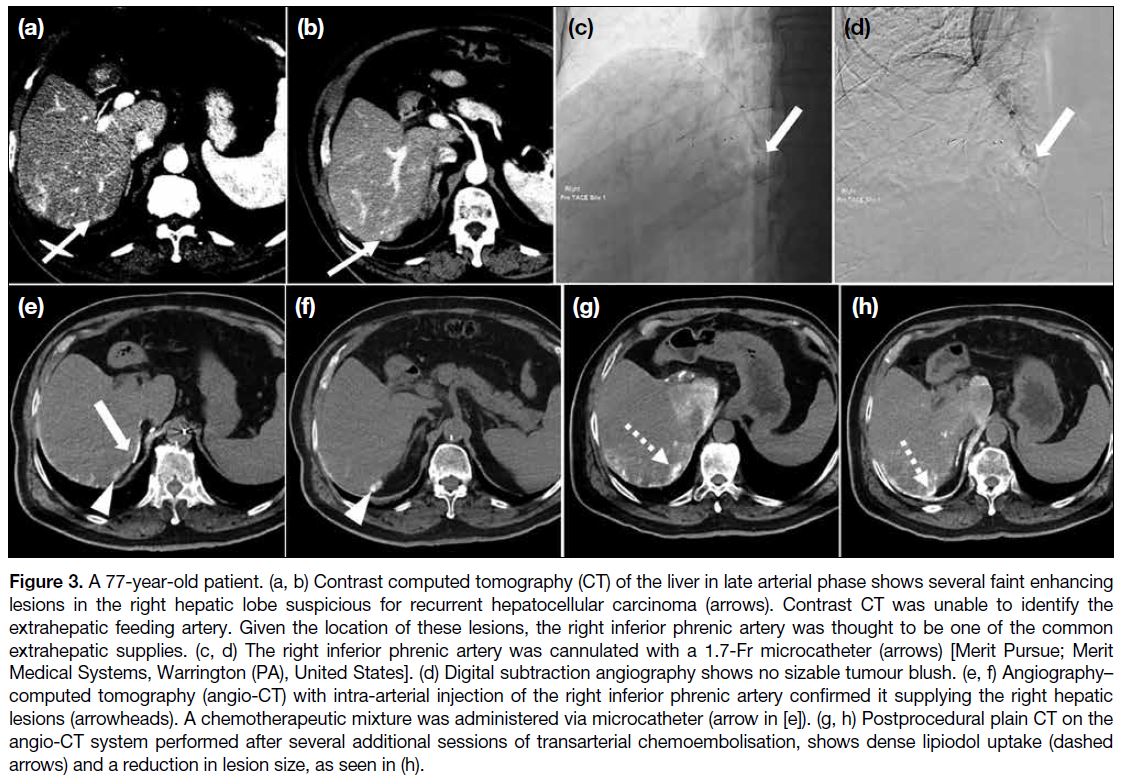

A 77-year-old hepatitis B carrier with a history of left

hepatectomy for HCC was later found to have multifocal

recurrent HCCs. Multiple TACEs were performed via

different branches of the right hepatic artery, but the

patient was still found to have persistent right hepatic

lobe HCCs on follow-up CT scan (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A 77-year-old patient. (a, b) Contrast computed tomography (CT) of the liver in late arterial phase shows several faint enhancing

lesions in the right hepatic lobe suspicious for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma (arrows). Contrast CT was unable to identify the

extrahepatic feeding artery. Given the location of these lesions, the right inferior phrenic artery was thought to be one of the common

extrahepatic supplies. (c, d) The right inferior phrenic artery was cannulated with a 1.7-Fr microcatheter (arrows) [Merit Pursue; Merit

Medical Systems, Warrington (PA), United States]. (d) Digital subtraction angiography shows no sizable tumour blush. (e, f) Angiography–computed tomography (angio-CT) with intra-arterial injection of the right inferior phrenic artery confirmed it supplying the right hepatic

lesions (arrowheads). A chemotherapeutic mixture was administered via microcatheter (arrow in [e]). (g, h) Postprocedural plain CT on the

angio-CT system performed after several additional sessions of transarterial chemoembolisation, shows dense lipiodol uptake (dashed

arrows) and a reduction in lesion size, as seen in (h).

Enhancing Treatment Efficacy of Drug-Eluting

Bead Transarterial Chemoembolisation

In drug-eluting bead (DEB)-TACE, angio-CT offers

additional benefits beyond its higher sensitivity for

detecting viable tumour components and feeding

arteries. Unlike conventional TACE using lipiodol,

DEB-TACE does not produce lipiodol staining to assess

immediate treatment response. Therefore, an immediate

post-procedural angio-CT with intra-arterial contrast

injection can help identify residual arterial enhancement

and guide further management, such as the need for

additional drug administration.

A 64-year-old patient had a large right hepatic lobe

HCC. The lesion was too large for resection or ablation.

Hence, he underwent several episodes of TACE.

However, the patient had poor response with suboptimal

tumour lipiodol staining and rapid lipiodol washout,

and was referred for DEB-TACE. Right hepatic artery

DSA showed three suspicious arterial feeders, which

were selectively cannulated with a microcatheter (2.8Fr

Meri Maestro Swanneck microcatheter; Merit Medical

Systems, Inc, South Jordan [UT], United States). This

case demonstrated the ability of precise identification

of feeding arteries in DEB-TACE using angio-CT,

particularly for equivocal or indeterminate feeders in

DSA and preprocedural CT. It also enabled assessment

of immediate treatment response and detection of

residual lesions (Figure 4).

Figure 4. A 64-year-old patient. (a) Preprocedural contrast computed tomography liver in

late arterial phase, showing poor lipiodol staining at the anterior aspect of the lesion with a viable arterial enhancing component (dashed circle). (b) Target site 1 cannulated with microcatheter. Digital subtraction angiography showed tumour blush (arrow). (c) The arterial component was confirmed with intra-arterial injection using angiography–computed tomography (angio-CT), showing arterial blush (arrowhead). Drug-eluting beads loaded with chemomixture were administered. (d) Immediate post–drug-eluting bead transarterial chemoembolisation (DEB-TACE) angio-CT with intra-arterial injection at the feeder showing reduction in the enhancing component (arrow). (e) Digital subtraction angiography of Target site 2 shows no sizable tumour blush. (f) However, angio-CT with an intra-arterial injection shows arterially enhancing viable component (arrowhead). Drug-eluting beads loaded with chemomixture were administered. (g) Immediate post–DEB-TACE angio-CT with intra-arterial injection at feeder shows significant reduction in arterial enhancing component (arrow). (h, i) Digital subtraction angiography of Target site 3 shows no sizable tumour blush, in concordance with intra-arterial injection angio-CT showing no arterial enhancing viable component. No drug was administered at this site.

Tumour Ablation

Improving Target Visualisation

Identifying target hepatic tumours with ultrasound for

ablation can be difficult due to cirrhotic liver or prior

treatment changes. Contrast CT significantly helps with

lesion identification and ablation probe placement. Some

operators also perform intraprocedural angio-CT with

intra-arterial injection for tumour identification and

ablation margin monitoring,[1] [4] improving the precision

of ablation and treatment response monitoring.

Increasing Ease for Artificial Ascites Creation

For creation of artificial ascites, an angio-catheter is

first inserted into the peritoneal space under ultrasound

guidance, followed by a guidewire, then exchanged to a

catheter for dextrose infusion. Using angio-CT, operators

can safely manipulate the guidewire and exchange to the

catheter under real-time fluoroscopy, confirm catheter

position on CT, and proceed to image-guided ablation.

All steps involving different imaging modalities can be

performed on the same table without moving the patient.

Radiofrequency Ablation of Liver Metastases

An 85-year-old patient with a history of colonic cancer

and prior liver metastases treated with ablations. Follow-up

CT showed several new liver metastases, and the

patient was referred for image-guided radiofrequency

ablation. On-table ultrasound identified several nodules

in the right hepatic lobe, but it was difficult to distinguish

them from prior ablation zones. Triphasic angio-CT liver

showed several liver metastatic lesions (Figure 5).

Figure 5. (a-c) An 85-year-old patient. Three hypoenhancing nodules in segments 8 and 4a (circles), suggestive of liver metastases. (d-f)

For creation of artificial ascites, a 16-gauge angio-catheter (Becton Dickson, Franklin Lakes [NJ], United States) was used to target

the perihepatic space under ultrasound guidance, which was then exchanged to a 6-Fr catheter (Boston Scientific, Marlborough [MA],

United States) over a 0.035-inch Terumo guidewire (Tokyo, Japan) under fluoroscopy. The catheter tip was confirmed with angiography–computed tomography (angio-CT), followed by infusion of 5% dextrose solution. (g, h) Each lesion was targeted with an ablation antenna

under ultrasound and computed tomography guidance (antenna tips indicated by circles), with a 12-minute ablative cycle performed. (i)

Postprocedural computed tomography showing a hyperdense layer (arrow) in the artificial ascites and noted blood-stained fluid in drain. (j-l)

Immediate multiphasic images were acquired by angio-CT, showing no evidence of active bleeding or pseudoaneurysm. The patient’s vital

signs were stable and he was sent back to the ward for close observation.

Acute Haemorrhage Embolisation

Improving Detection of Bleeding Source

In cases of acute bleeding, angio-CT angiogram can

detect bleeding sources too small or slow to be identified

on CT with intravenous contrast.[1] With 3D reformatting,

the precise location of the bleeder can be accurately

determined.

Quicker Cessation of Bleeder

Unstable patients with active bleeding can be transferred

directly to angio-CT for urgent CT, followed by immediate embolisation on the same table. This

eliminates the need to move patients between the

diagnostic CT and IR suites, allowing quicker

haemorrhage control and improved outcomes.

Embolisation of Haemorrhagic Renal Tumour

A 70-year-old patient was incidentally found to have

an enhancing soft tissue mass at the lower pole of left

kidney. Ultrasound-guided biopsy was performed, but

the patient developed left flank pain with a haemoglobin

drop from 14.1 g/dL to 11.6 g/dL on day 1 post-biopsy.

Urgent CT of the kidney found intratumoural

haemorrhage and trace left haemoretroperitoneum.

Post-embolisation haemoglobin level remained stable,

with post-embolisation day 5 follow-up CT showing

no progression or active bleeding. The patient was later

discharged (Figure 6).

Figure 6. (a) A 70-year-old patient. Pre-contrast computed tomography (CT) of the kidneys shows a left renal lower pole mass with

internal hyperdensities (arrow), suggesting intratumoural haemorrhage. Arterial phase CT showed no pseudoaneurysm or active contrast

extravasation. (b) The left main renal artery was cannulated with a catheter (5Fr C1 catheter; Cordis, Miami Lakes [FL], United States) and

digital subtraction angiography performed, showing a long curved tortuous inferior segmental artery to the left lower pole (arrow), with

dysplastic distal branches. (c-e) With angiography–computed tomography, this was confirmed to be the feeding artery (arrowheads) to the

haemorrhagic renal lesion, without pseudoaneurysm or active contrast extravasation. (f) The feeder was selectively cannulated with a 2.4-Fr

microcatheter (Maestro; Merit Medical Systems, Warrington [PA], United States) with digital subtraction angiography confirming its supply

to the renal lesion (dashed arrow). Embolisation was performed with Embospheres 500-700 μm (Merit, Warrington [PA], United States) until

stasis was achieved. (g) Check of left renal angiogram showing successful occlusion of the bleeding artery.

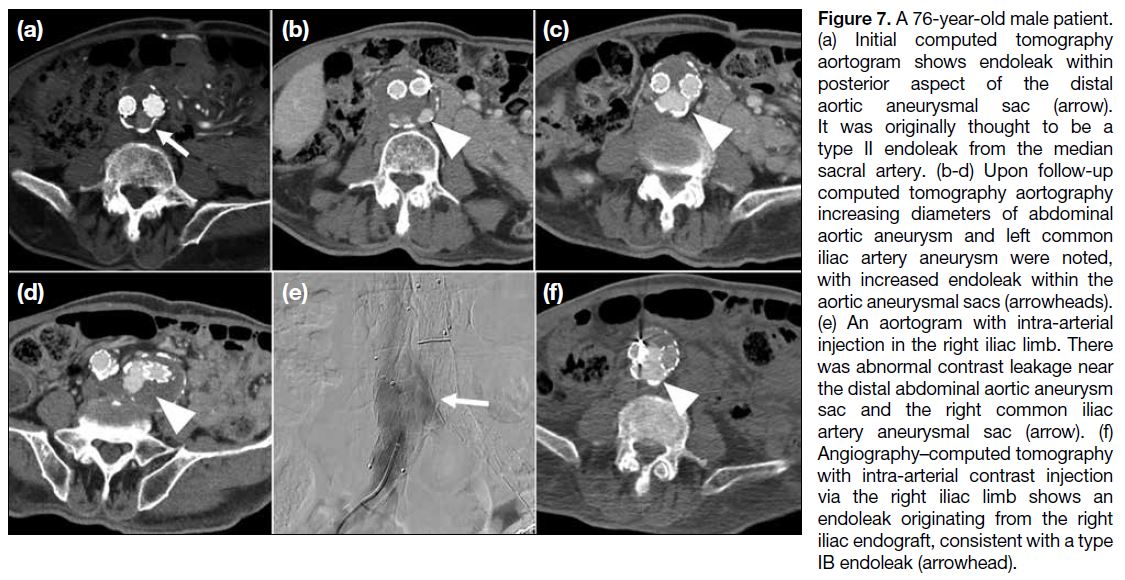

Endoleak Detection and Management

Diagnosis for Endoleak

Angio-CT combines the benefits of DSA and CT by integrating real-time flow dynamics with detailed cross-sectional

anatomy. This allows comprehensive and

accurate evaluation of the type and site of endoleak, as

demonstrated in the following case.

A 76-year-old male patient with infrarenal abdominal

aortic aneurysm and left common and internal iliac artery

aneurysms was managed with endovascular aneurysm

repair. A diagnostic aortogram was performed 1 year

after endovascular aneurysm repair to clarify the type

and site of endoleak. 5Fr Multipurpose catheter (Merit

Medical, South Jordan [UT], United States) was then navigated to the left iliac limb and superior mesenteric

artery, with angio-CT angiogram performed to exclude

other endoleak sites. The patient was managed with

extension of the right iliac limb endograft (Figure 7).

Figure 7. A 76-year-old male patient.

(a) Initial computed tomography

aortogram shows endoleak within

posterior aspect of the distal

aortic aneurysmal sac (arrow).

It was originally thought to be a

type II endoleak from the median

sacral artery. (b-d) Upon follow-up

computed tomography aortography

increasing diameters of abdominal

aortic aneurysm and left common

iliac artery aneurysm were noted,

with increased endoleak within the

aortic aneurysmal sacs (arrowheads).

(e) An aortogram with intra-arterial

injection in the right iliac limb. There

was abnormal contrast leakage near

the distal abdominal aortic aneurysm

sac and the right common iliac

artery aneurysmal sac (arrow). (f)

Angiography–computed tomography

with intra-arterial contrast injection

via the right iliac limb shows an

endoleak originating from the right

iliac endograft, consistent with a type

IB endoleak (arrowhead).

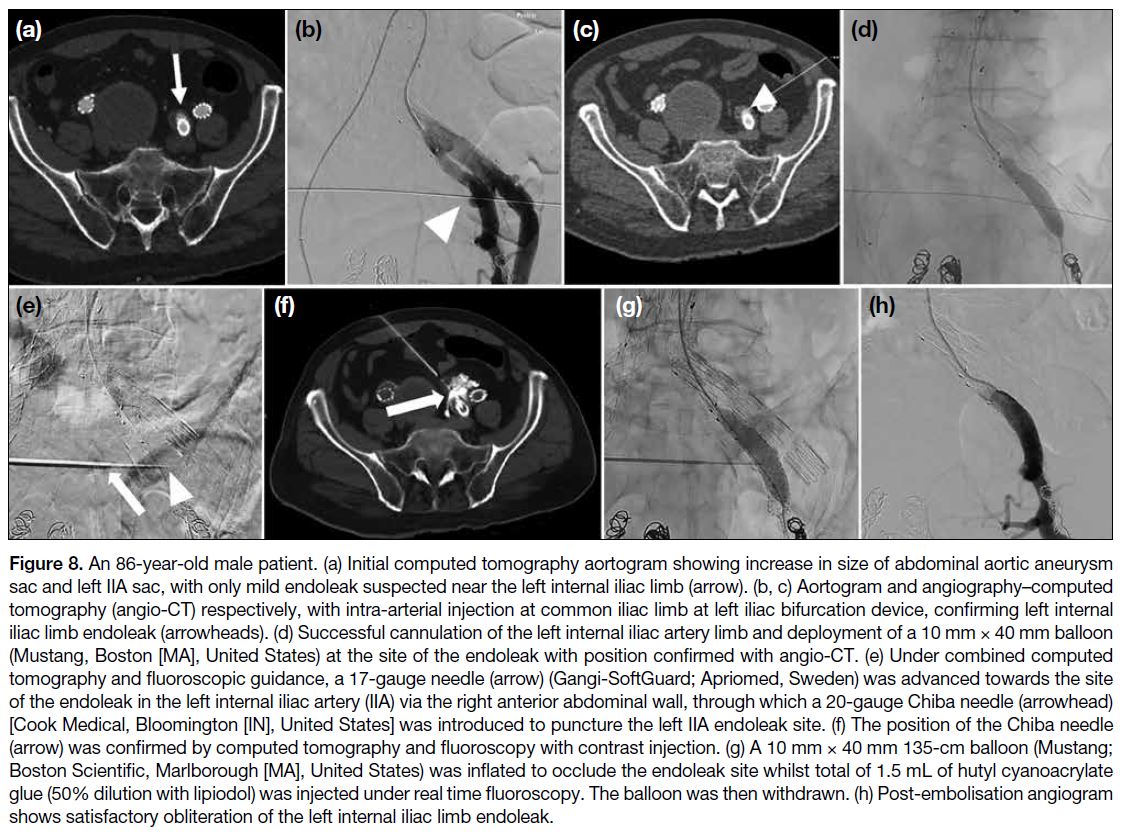

Embolisation of Endoleak

Angio-CT is useful for endoleak treatment. A CT

aortogram with intra-arterial injection enables precise

localisation of the endoleak, followed by targeting

under combined CT and fluoroscopic guidance, and

embolisation under real-time fluoroscopy. Final

placement of embolic material and any immediate complications can be verified with angio-CT. The system

allows the entire multimodality process to be performed

on the same table.

An 86-year-old male patient with an infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm, bilateral common iliac artery and IIA

aneurysms was treated with endovascular aneurysm

repair, right IIA coil embolisation and left iliac bifurcation

device. The endoleak was targeted for balloon-assisted

percutaneous transluminal glue embolisation in the same session. With angio-CT enabling seamless, efficient

transition between CT angiogram and fluoroscopy, the

operator safely targeted the endoleak site for embolisation

without injuring adjacent organs or damaging the stent

(Figure 8).

Figure 8. An 86-year-old male patient. (a) Initial computed tomography aortogram showing increase in size of abdominal aortic aneurysm

sac and left IIA sac, with only mild endoleak suspected near the left internal iliac limb (arrow). (b, c) Aortogram and angiography–computed

tomography (angio-CT) respectively, with intra-arterial injection at common iliac limb at left iliac bifurcation device, confirming left internal

iliac limb endoleak (arrowheads). (d) Successful cannulation of the left internal iliac artery limb and deployment of a 10 mm × 40 mm balloon

(Mustang, Boston [MA], United States) at the site of the endoleak with position confirmed with angio-CT. (e) Under combined computed

tomography and fluoroscopic guidance, a 17-gauge needle (arrow) (Gangi-SoftGuard; Apriomed, Sweden) was advanced towards the site

of the endoleak in the left internal iliac artery (IIA) via the right anterior abdominal wall, through which a 20-gauge Chiba needle (arrowhead)

[Cook Medical, Bloomington [IN], United States] was introduced to puncture the left IIA endoleak site. (f) The position of the Chiba needle

(arrow) was confirmed by computed tomography and fluoroscopy with contrast injection. (g) A 10 mm × 40 mm 135-cm balloon (Mustang;

Boston Scientific, Marlborough [MA], United States) was inflated to occlude the endoleak site whilst total of 1.5 mL of hutyl cyanoacrylate

glue (50% dilution with lipiodol) was injected under real time fluoroscopy. The balloon was then withdrawn. (h) Post-embolisation angiogram

shows satisfactory obliteration of the left internal iliac limb endoleak.

Other Cross-Modalities Applications

Percutaneous Embolisation of Pulmonary Vein

Pseudoaneurysm

The angio-CT system is valuable in complex IR cases

requiring precise target localisation with CT and

real-time fluoroscopic guidance, as illustrated in the

following case. An 88-year-old patient with multiple

co-morbidities and a history of Stanford type A aortic

dissection managed conservatively was admitted with

haemoptysis of 50 to 100 mL/day. Haemoglobin level

dropped from 10.8 g/dL to 7.7 g/dL despite on transamin

and repeated blood transfusions. He required oxygen

support at 2 L/min via mask. An urgent CT aortogram

was performed, and the patient was referred for

angiogram for lesion characterisation and subsequent

management. His condition improved, with haemoptysis

level reduced to 10 mL/day. Haemoglobin level remained stable at 7 to 8 g/dL and oxygen support was weaned off (Figure 9).

Figure 9. (a) An 88-year-old patient. Urgent computed tomography aortogram showing pulmonary consolidation and haemorrhage in the

left lower lobe, with a 0.9-cm enhancing lesion within the consolidation (arrow). It is closely abutting the left inferior pulmonary vein, raising

suspicion of a pulmonary venous pseudoaneurysm. Known Stanford type A aortic dissection was static with no mediastinal haematoma. (b,

c) Left pulmonary angiogram shows no corresponding lesion in the left lower lobe in pulmonary arterial and parenchymal phases. (d, e) An

enhancing nodule in the left lower lobe appeared after pulmonary arterial and parenchymal phases (arrowhead in [d]), consistent with the

computed tomography (CT) findings that it originated from the left inferior pulmonary vein rather than pulmonary artery. The location was

confirmed in angiography–computed tomography (circle in [e]) for embolisation planning. (f, g) Under combined fluoroscopic and computed

tomography guidance, a 20-gauge Chiba needle (Cook Medical, Bloomington [IN], United States) was used to percutaneously access

the pseudoaneurysm sac. Under fluoroscopy, contrast injection confirmed needle positioning with opacification of the pseudoaneurysm

sac (arrow in [f]) and the outflowing pulmonary vein (arrowhead in [g]). (h, i) Two 4 mm × 10 cm embolisation coils (Concerto; Medtronic,

Minneapolis [MN], United States) [circle in (h)] were successfully deployed under fluoroscopy, with coil position confirmed with computed

tomography (circle in [i]). (j) Further attempt coiling of aneurysm was not successful. 0.6 mL of hutyl cyanoacrylate glue (50% dilution

with lipiodol) was injected under fluoroscopy for complete sac embolisation. (k) Postprocedural computed tomography shows complete

obliteration of the pseudoaneurysm by glue and coils without residual contrast opacification (circle).

This case demonstrates successful lesion targeting

using a percutaneous approach, where reliance on either

fluoroscopy or intermittent CT alone poses a high risk

of injury to vital internal organs. With the advantage

of angio-CT allowing seamless transition between

CT and fluoroscopy, the operator safely punctured the

target without harming surrounding organs, followed by

embolisation under real-time fluoroscopy.

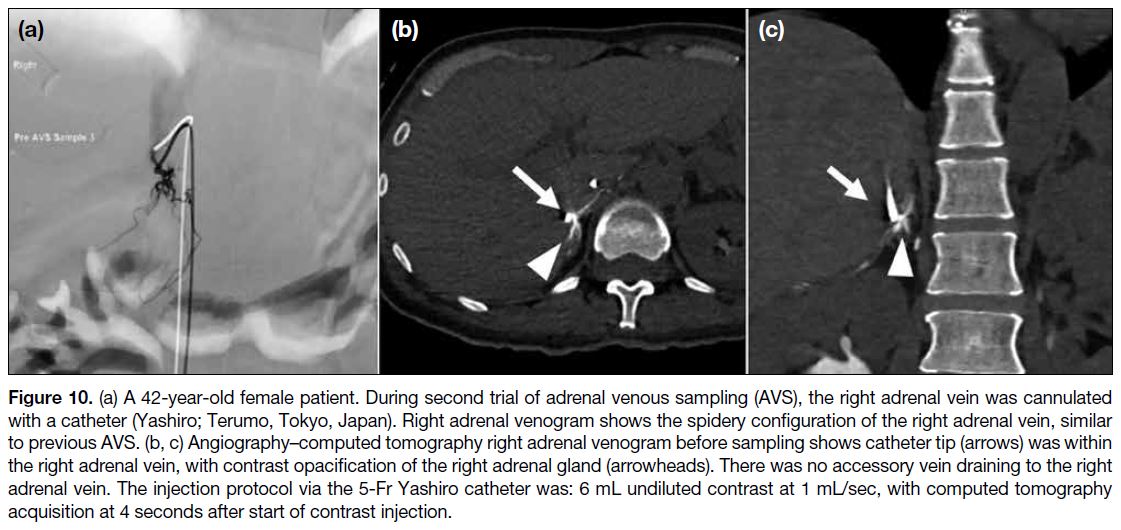

Adrenal Venous Sampling

Recognition and cannulation of the right adrenal

vein is one of the most challenging aspects of adrenal

venous sampling (AVS). Common issues include

catheter dislodgement, incorrect or deep cannulation, or

anatomical variants like an accessory hepatic vein that

may dilute cortisol. In such cases, CT during AVS can

help delineate anatomy and confirm catheter position.[5]

Compared to CBCT, CT offers superior image quality

and faster acquisition, reducing the risk of catheter

dislodgement. A case illustration is presented below.

A 42-year-old female patient with primary

hyperaldosteronism and hypertension previously failed

AVS, as the right adrenal venous sample lacked sufficient

cortisol to meet the required selectivity index, despite

venography showing a typical spidery configuration

on retrospective review. The cause of failure was

indeterminate and she was referred for a second AVS.

Angio-CT right venogram was performed before and just

after right sampling to: (1) ensure correct cannulation of

the right adrenal vein; (2) ensure the catheter remained in situ during sampling; and (3) exclude anatomical

variants such as an accessory hepatic vein. Post-sampling

angio-CT confirmed catheter position. Sampling of

right adrenal veins was successful reaching a selectivity

index of 15. The patient was diagnosed with a left-sided

aldosterone-secreting tumour and is pending surgery

(Figure 10).

Figure 10. (a) A 42-year-old female patient. During second trial of adrenal venous sampling (AVS), the right adrenal vein was cannulated

with a catheter (Yashiro; Terumo, Tokyo, Japan). Right adrenal venogram shows the spidery configuration of the right adrenal vein, similar

to previous AVS. (b, c) Angiography–computed tomography right adrenal venogram before sampling shows catheter tip (arrows) was within

the right adrenal vein, with contrast opacification of the right adrenal gland (arrowheads). There was no accessory vein draining to the right

adrenal vein. The injection protocol via the 5-Fr Yashiro catheter was: 6 mL undiluted contrast at 1 mL/sec, with computed tomography

acquisition at 4 seconds after start of contrast injection.

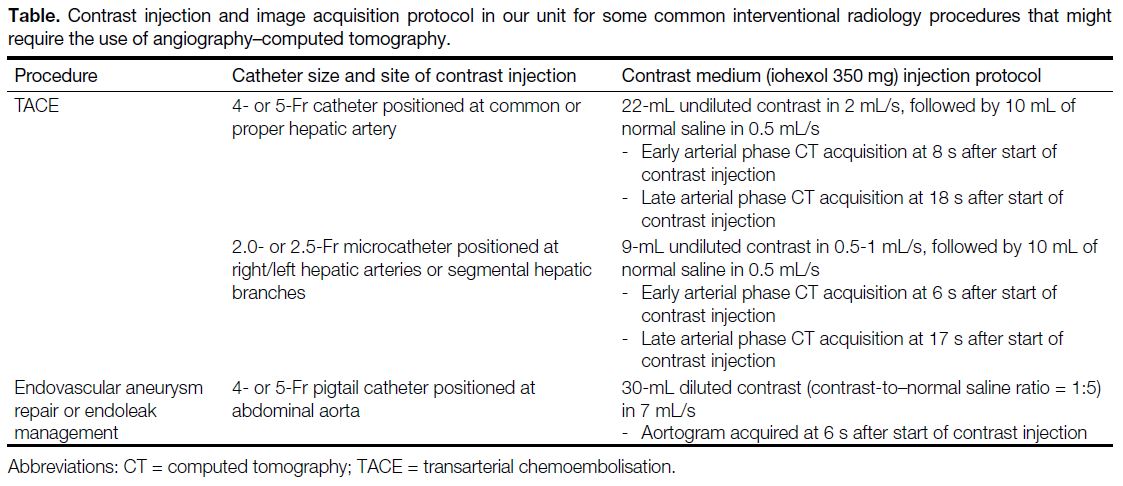

Details of the contrast injection and image acquisition

protocols for commonly performed vascular procedures requiring CT acquisition with our angio-CT system are

provided in the Table.

Table. Contrast injection and image acquisition protocol in our unit for some common interventional radiology procedures that might require the use of angiography–computed tomography

DISCUSSION

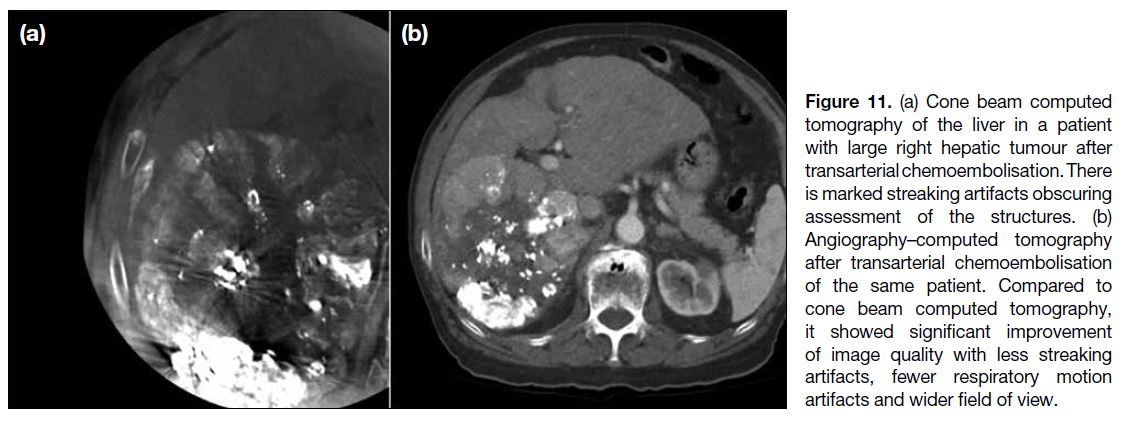

The above cases highlight the applications and

advantages of using the angio-CT system in various

IR procedures. Compared to CBCT previously used in

our unit, the image quality of CT hepatic angiogram in

angio-CT surpasses CBCT in visualisation of tumour,

identification of tumour arterial feeders, reduction of

streaking artefacts, wider field of view including the whole liver, fewer respiratory motion artefacts, and

higher overall subjective image quality[2] (Figure 11). It

also allows immediate postprocedural imaging to assess

treatment response, such as immediate lipiodol uptake

and presence of residual lesions, which are limited by

streaking and respiratory artefacts in CBCT.

Figure 11. (a) Cone beam computed

tomography of the liver in a patient

with large right hepatic tumour after

transarterial chemoembolisation. There

is marked streaking artifacts obscuring

assessment of the structures. (b)

Angiography–computed tomography

after transarterial chemoembolisation

of the same patient. Compared to

cone beam computed tomography,

it showed significant improvement

of image quality with less streaking

artifacts, fewer respiratory motion

artifacts and wider field of view.

For angio-CT hepatic arteriogram, a smaller amount of

contrast can be used for direct hepatic artery injection

compared to systemic intravenous injection.[4] [5] In DEB-TACE,

multiple contrast injections are typically required to verify target lesions. Therefore, using angio-CT may

help reducing fluid overload and contrast load, which

is beneficial to patients with liver cirrhosis with pre-existing

fluid status disturbances.

In suspected complications during or immediately after

IR, angio-CT can be promptly performed with multiphasic

studies to detect bleeding, without transferring the patient

to diagnostic CT. This allows immediate diagnosis and

treatment, such as urgent embolisation.

Apart from the above examples, angio-CT can improve

procedural outcomes in the following scenarios.

A common application is combined TACE and ablation

for liver cancers, where TACE is first performed first

to devascularise and stain the tumour, followed by

ablation in the same session. The ablation margin can

be monitored during and after with intra-arterial contrast

injection, improving margin visualisation.

In hypervascular soft tissue or bone tumours, such

as renal cell or thyroid carcinoma bone metastases,

embolisation can be done first under angiography to

reduce its vascularity, followed by CT-guided ablation

in the same session. This reduces haemorrhagic risks,

especially in hypervascular tumours.[5] [7]

In emergencies requiring urgent embolisation, such

as trauma or ruptured HCC, the patient can be directly

transferred to angio-CT for urgent CT angiogram and

embolisation. After reviewing images on the angio-CT workstation, the operator can proceed immediately

without transferring the patient from diagnostic

CT to IR suite. This is crucial when the patient is

haemodynamically unstable and also shortens scan-to-needle

time, potentially improving outcomes.

A major drawback of angio-CT is cost and space.

Depending on vendor and performance, angio-CT is

approximately 1.5 to 2 times more expensive than flat

panel CBCT.[8] It also requires more space compared with

C-arm CBCT, possibly needing re-design of the IR suite.

Radiation dose between angio-CT and CBCT remains

debated. A study on CT-guided lung biopsy showed

angio-CT delivered 1.2 to 1.7 times higher effective

dose than CBCT (mean: 15.77 mSv vs. 10.68 mSv).[9]

However, another study during TACE showed angio-CT

had 2.5 times lower effective dose than CBCT (median:

15.4 vs. 39.2 mSv).[10] Dose indices differ: angio-CT uses

dose-length product while CBCT uses dose-area product.

As these comparisons were based on estimated effective

doses using region-specific conversion factors and

phantom calculations, uncertainties must be considered

when interpreting dosage results.

The integration of angiography unit and dedicated CT

scanner into a hybrid angio-CT system is a revolutionary

technology for IR. By enabling detailed anatomical

characterisation and visualisation of critical structures,

angio-CT is a valuable tool to enhance the patient

outcome and reduce procedural risks in complex

interventional procedures.

REFERENCES

1. Taiji R, Lin EY, Lin YM, Yevich S, Avritscher R, Sheth RA, et al.

Combined angio-CT systems: a roadmap tool for precision

therapy in interventional oncology. Radiol Imaging Cancer.

2021;3:e210039. Crossref

2. Lin EY, Jones AK, Chintalapani G, Jeng ZS, Ensor J, Odisio BC.

Comparative analysis of intra-arterial cone-beam versus

conventional computed tomography during hepatic arteriography

for transarterial chemoembolization planning. Cardiovasc Intervent

Radiol. 2019;42:591-600. Crossref

3. Wang H, Han Y, Chen G, Jin L. Imaging biomarkers on angio-CT for predicting the efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2023;13:4077-88. Crossref

4. van Tilborg AA, Scheffer HJ, Nielsen K, van Waesberghe JH,

Comans EF, van Kuijk C, et al. Transcatheter CT arterial

portography and CT hepatic arteriography for liver tumor

visualization during percutaneous ablation. J Vasc Interv Radiol.

2014;25:1101-11.e4. Crossref

5. Kobayashi K, Ozkan E, Tam A, Ensor J, Wallace MJ, Gupta S. Preoperative embolization of spinal tumors: variables affecting intraoperative blood loss after embolization. Acta Radiol.

2012;53:935-42. Crossref

6. Puijk RS, Nieuwenhuizen S, van den Bemd BA, Ruarus AH,

Geboers B, Vroomen LG, et al. Transcatheter CT hepatic

arteriography compared with conventional CT fluoroscopy

guidance in percutaneous thermal ablation to treat colorectal liver

metastases: a single-center comparative analysis of 2 historical

cohorts. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2020;31:1772-83. Crossref

7. Owen RJ. Embolization of musculoskeletal bone tumors. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2010;27:111-23. Crossref

8. Tanaka T, Arai Y, Inaba Y, Inoue M, Nishiofuku H, Anai H, et al.

Current role of hybrid CT/angiography system compared with

C-arm cone beam CT for interventional oncology. Br J Radiol.

2014;87:20140126. Crossref

9. Strocchi S, Colli V, Conte L. Multidetector CT fluoroscopy

and cone-beam CT-guided percutaneous transthoracic biopsy:

comparison based on patient doses. Radiat Prot Dosimetry.

2012;151:162-5. Crossref

10. Piron L, Le Roy J, Cassinotto C, Delicque J, Belgour A, Allimant C,

et al. Radiation exposure during transarterial chemoembolization:

angio-CT versus cone-beam CT. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol.

2019;42:1609-18. Crossref