Multimodality Imaging and Interventional Radiological Management of Neurologic Complications of Infective Endocarditis

PICTORIAL ESSAY

Hong Kong J Radiol 2025;28:Epub 9 December 2025

Multimodality Imaging and Interventional Radiological

Management of Neurologic Complications of Infective Endocarditis

EH Chan, HM Kwok, NY Pan, LF Cheng, JKF Ma

Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Kowloon West Cluster, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr EH Chan, Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Kowloon West Cluster, Hong Kong SAR,

China. Email: eh278@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 2 September 2024; Accepted: 1 November 2024. This version may differ from the final version when published in an issue.

Contributors: All authors designed the study, acquired and analysed the data. EHC drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the

manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for

publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Central Institutional Review Board of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: CIRB-2024-012-4). The requirement for patient consent was waived by the Board due to retrospective nature of the study.

INTRODUCTION

Infective endocarditis (IE) affects 1.7 to 6.2 individuals

per 100,000 population per year and remains a

life-threatening condition.[1] Staphylococci are the

most frequent causative organisms.[1] [2] Neurological

complications are the most common and severe

extracardiac complications of IE[3] and have been reported

as the presenting symptom in up to 47% of cases.[4] These

complications are caused by cerebral septic embolisation

of endocardial vegetations. Patients with neurological

complications have significantly higher mortality

compared to those without (24% vs. 10%; p < 0.03).[3]

Neuroimaging leads to the identification of valvular

surgery indications in about 22% of patients with

symptoms of neurological complications of IE, and in

19% of asymptomatic IE patients.[2] Up to 82% of patients

have cerebral lesions on magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI) performed within 7 days after admission.[1]

MRI findings influence diagnostic classification and

other clinical decisions in 28% of patients, including

modification of medical or surgical treatment plans.[5]

According to the 2015 European Society of Cardiology guidelines,[6] the presence of cerebral emboli in patients

with left-sided valvular vegetations greater than 10

mm is an indication for urgent valve surgery to prevent

further embolisms. Familiarity with the neurological

imaging findings is essential for early diagnosis of this

complication of IE, allowing a window for early and

specific treatment, thereby reducing mortality. However,

the wide spectrum of presentations on neuroimaging

poses diagnostic challenges to radiologists, especially

when cerebral septic embolism is the first presentation.

This pictorial essay aims to review the spectrum of

presentations and the use of multimodality imaging to

increase awareness of the classic diagnostic imaging

findings of cerebral septic emboli secondary to IE, and to

highlight the role of interventional radiology in clinical

management.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of IE is made according to the Modified

Duke criteria,[1] which include the presence of major

arterial emboli, mycotic aneurysm, and intracranial

haemorrhage as part of its minor criteria.

Computed tomography (CT) is the first-line imaging

study in patients with neurological symptoms as it is

readily available. MRI, including susceptibility-weighted

imaging (SWI) and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI),

is required to detect more subtle findings such as cerebral

microbleeds and early infarcts. Further investigations

with computed tomographic angiography (CTA) or

magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) are useful for

detecting mycotic aneurysms, while digital subtraction

angiography (DSA) remains the gold standard and

should be performed in clinically suspicious cases with

negative CTA or MRA.[7] There is growing support for

performing screening MRI in patients with suspected

or confirmed IE, given the frequency of asymptomatic

findings and its usefulness in decision-making.

However, its cost-effectiveness and impact on mortality

reduction remain to be seen.[8]

Imaging Spectrum

Neurological complications of IE may present as cerebral

infarcts, micro- or macro-haemorrhage, abscess, and

meningitis. The pooled frequency of individual findings

on MRI is as follows: acute ischaemic lesions (61.9%),

cerebral microbleeds (52.9%), macro-haemorrhages

(24.7%), abscess or meningitis (9.5%), and intracranial

mycotic aneurysm (6.2%).[8] Accurate identification of these lesions allows early diagnosis of IE

complications and individualised management strategies.

Ischaemic Stroke

Ischaemic stroke is the most common neurological

manifestation of IE. It can result from embolisation

of endocardial vegetations, leading to occlusion of

intracerebral arteries.[3] The incidence of cerebral

ischaemia is correlated with left-sided endocarditis

(especially involving the anterior mitral valve leaflet),

larger endocardial vegetation size (>10 mm), mobile

vegetations, and Staphylococcus aureus infection.[3]

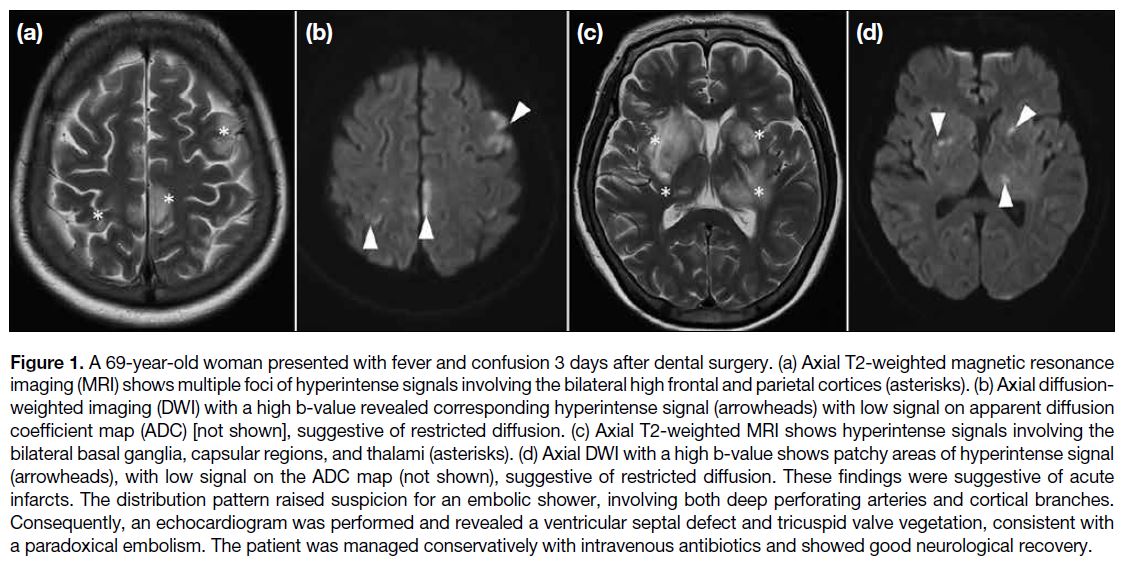

Disseminated ischaemic lesions may result from multiple

emboli occurring over a short period or fragmentation of

an embolus in the heart or aorta. The presence of multiple

cortical and subcortical cerebral infarcts of varying

ages within different vascular territories (especially

watershed areas) or bihemispheric involvement suggests

the diagnosis of septic emboli[4] (Figure 1). Large emboli

tend to cause cortical infarction in the middle cerebral

artery (MCA) territory, while smaller emboli often lodge

distally in terminal cortical branches of the anterior

cerebral artery and MCA, resulting in small peripheral

infarcts at the grey-white matter junction.[9] It is worth

noting that isolated brainstem strokes are rarely caused

by cardioembolism.

Figure 1. A 69-year-old woman presented with fever and confusion 3 days after dental surgery. (a) Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) shows multiple foci of hyperintense signals involving the bilateral high frontal and parietal cortices (asterisks). (b) Axial diffusion-weighted

imaging (DWI) with a high b-value revealed corresponding hyperintense signal (arrowheads) with low signal on apparent diffusion

coefficient map (ADC) [not shown], suggestive of restricted diffusion. (c) Axial T2-weighted MRI shows hyperintense signals involving the

bilateral basal ganglia, capsular regions, and thalami (asterisks). (d) Axial DWI with a high b-value shows patchy areas of hyperintense signal

(arrowheads), with low signal on the ADC map (not shown), suggestive of restricted diffusion. These findings were suggestive of acute

infarcts. The distribution pattern raised suspicion for an embolic shower, involving both deep perforating arteries and cortical branches.

Consequently, an echocardiogram was performed and revealed a ventricular septal defect and tricuspid valve vegetation, consistent with

a paradoxical embolism. The patient was managed conservatively with intravenous antibiotics and showed good neurological recovery.

DWI is useful for assessing the temporal relationship of

ischaemic lesions. Acute infarcts appear as hyperintense

on DWI and hypointense on apparent diffusion coefficient mapping. Over time, the apparent diffusion coefficient

signal increases and pseudonormalises in about 1 week,

signal increases and pseudonormalises in about 1 week,

while the DWI signal decreases and pseudonormalises in

about 2 weeks.[10]

Cerebral Abscesses and Meningitis

Cerebral abscesses and meningitis are uncommon

neurological manifestations of IE, occurring in up to

9.5% of patients.[8]

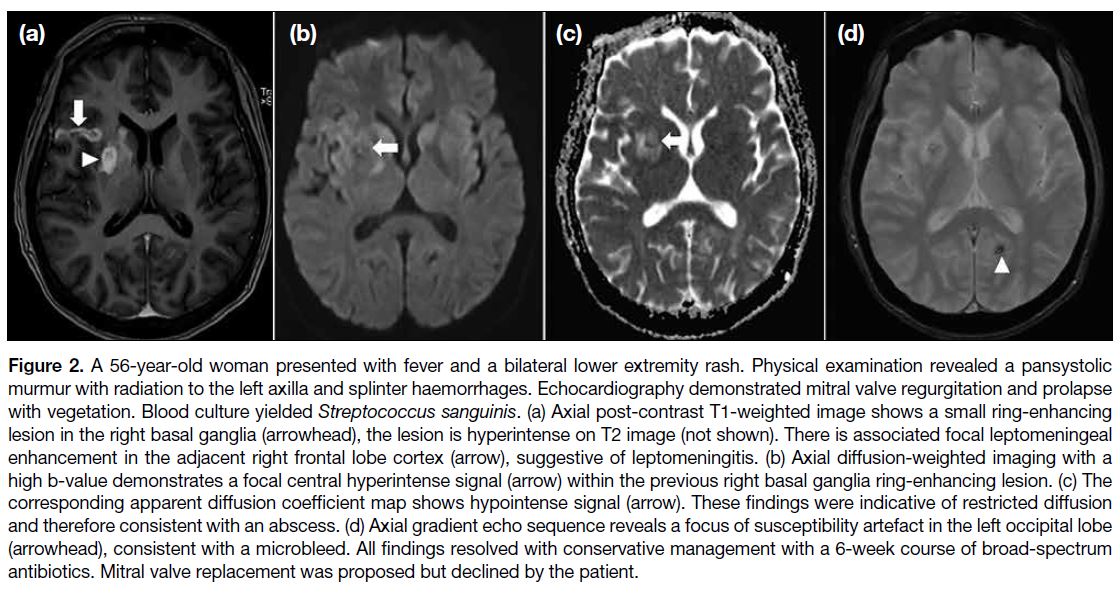

Typically, multiple abscesses appear in the MCA

territory at the grey-white matter junction, often with

vasogenic oedema and associated mass effect or haemorrhage.[3] On CT, cerebral abscesses are usually

hypodense with ring enhancement, but MRI is more

sensitive. Classic MRI features include lesions that are

hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense

on T2-weighted images, with ring enhancement and

central restricted diffusion (Figure 2). A dual rim sign,

two concentric rims surrounding the abscess cavity,

where the outer rim is hypointense and the inner is

relatively hyperintense, may be visible on SWI or T2-weighted imaging. Cerebral abscesses may also arise

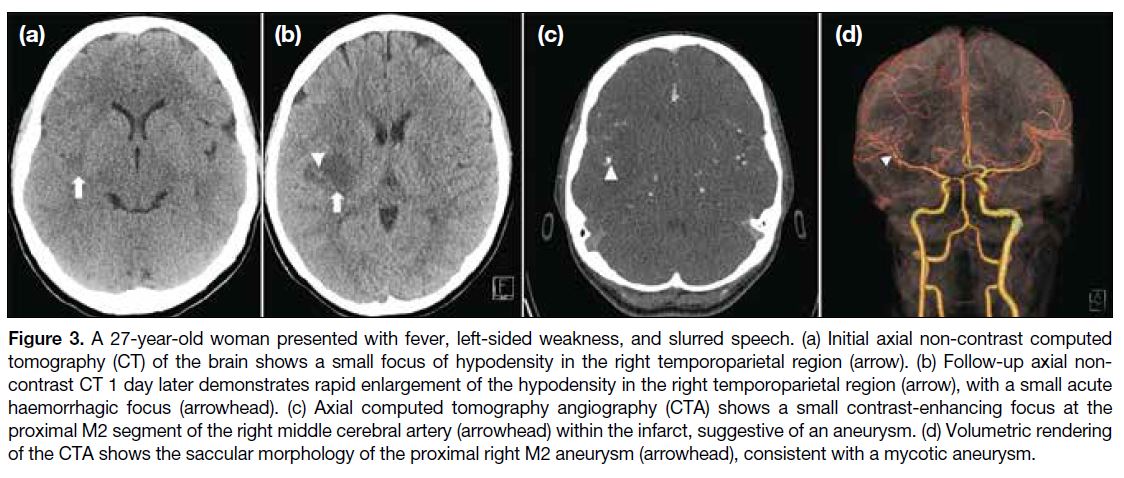

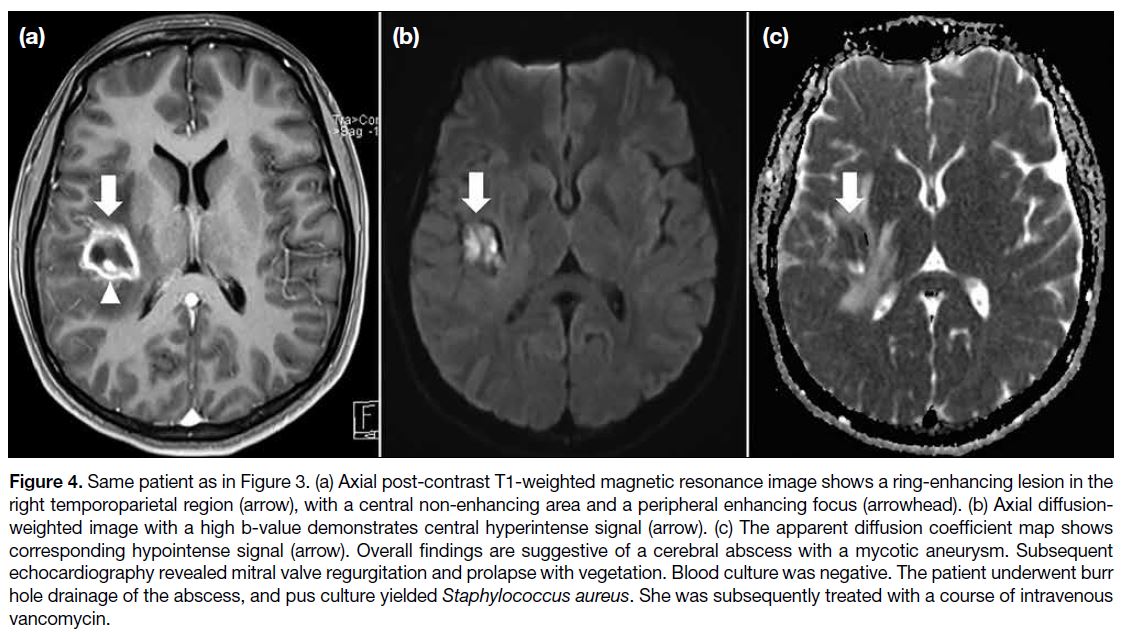

near mycotic aneurysms (Figures 3 and 4). The presence

of leptomeningeal enhancement on MRI or CT can

suggest concomitant meningitis.

Figure 2. A 56-year-old woman presented with fever and a bilateral lower extremity rash. Physical examination revealed a pansystolic

murmur with radiation to the left axilla and splinter haemorrhages. Echocardiography demonstrated mitral valve regurgitation and prolapse

with vegetation. Blood culture yielded Streptococcus sanguinis. (a) Axial post-contrast T1-weighted image shows a small ring-enhancing

lesion in the right basal ganglia (arrowhead), the lesion is hyperintense on T2 image (not shown). There is associated focal leptomeningeal

enhancement in the adjacent right frontal lobe cortex (arrow), suggestive of leptomeningitis. (b) Axial diffusion-weighted imaging with a

high b-value demonstrates a focal central hyperintense signal (arrow) within the previous right basal ganglia ring-enhancing lesion. (c) The

corresponding apparent diffusion coefficient map shows hypointense signal (arrow). These findings were indicative of restricted diffusion

and therefore consistent with an abscess. (d) Axial gradient echo sequence reveals a focus of susceptibility artefact in the left occipital lobe

(arrowhead), consistent with a microbleed. All findings resolved with conservative management with a 6-week course of broad-spectrum

antibiotics. Mitral valve replacement was proposed but declined by the patient.

Figure 3. A 27-year-old woman presented with fever, left-sided weakness, and slurred speech. (a) Initial axial non-contrast computed

tomography (CT) of the brain shows a small focus of hypodensity in the right temporoparietal region (arrow). (b) Follow-up axial non-contrast

CT 1 day later demonstrates rapid enlargement of the hypodensity in the right temporoparietal region (arrow), with a small acute

haemorrhagic focus (arrowhead). (c) Axial computed tomography angiography (CTA) shows a small contrast-enhancing focus at the

proximal M2 segment of the right middle cerebral artery (arrowhead) within the infarct, suggestive of an aneurysm. (d) Volumetric rendering

of the CTA shows the saccular morphology of the proximal right M2 aneurysm (arrowhead), consistent with a mycotic aneurysm.

Figure 4. Same patient as in Figure 3. (a) Axial post-contrast T1-weighted magnetic resonance image shows a ring-enhancing lesion in the

right temporoparietal region (arrow), with a central non-enhancing area and a peripheral enhancing focus (arrowhead). (b) Axial diffusion-weighted

image with a high b-value demonstrates central hyperintense signal (arrow). (c) The apparent diffusion coefficient map shows

corresponding hypointense signal (arrow). Overall findings are suggestive of a cerebral abscess with a mycotic aneurysm. Subsequent

echocardiography revealed mitral valve regurgitation and prolapse with vegetation. Blood culture was negative. The patient underwent burr

hole drainage of the abscess, and pus culture yielded Staphylococcus aureus. She was subsequently treated with a course of intravenous

vancomycin.

Cerebral Haemorrhages

Macrohaemorrhage usually results from haemorrhagic

transformation of ischaemic stroke, progression of

microhaemorrhages, or rupture of mycotic aneurysms.

Haemorrhagic transformation occurs more frequently in

embolic strokes (51%-71%) than in non-embolic strokes

(2%-21%)[11] and may present as petechial haemorrhage

or large parenchymal haematomas.[9] Cerebral ischaemic

lesions of varying ages across multiple vascular

territories and different haemorrhagic patterns would

raise suspicion for cardiac emboli. In the context of

underlying IE, cerebral septic embolism is a likely

diagnosis (Figure 5).

Septic emboli damage the endothelium and disrupt the

blood-brain barrier, resulting in inflammatory vasculitis

and small vessel rupture, often leading to cerebral

microbleeds or even intracerebral haemorrhage. One

study found that cerebral microbleeds in 57% of patients

with IE.[4] These microbleeds appear as hypointense foci

on T2* imaging or SWI MRI often in the cortex, and less

frequently in subcortical white matter, basal ganglia, or

posterior fossa.[4]

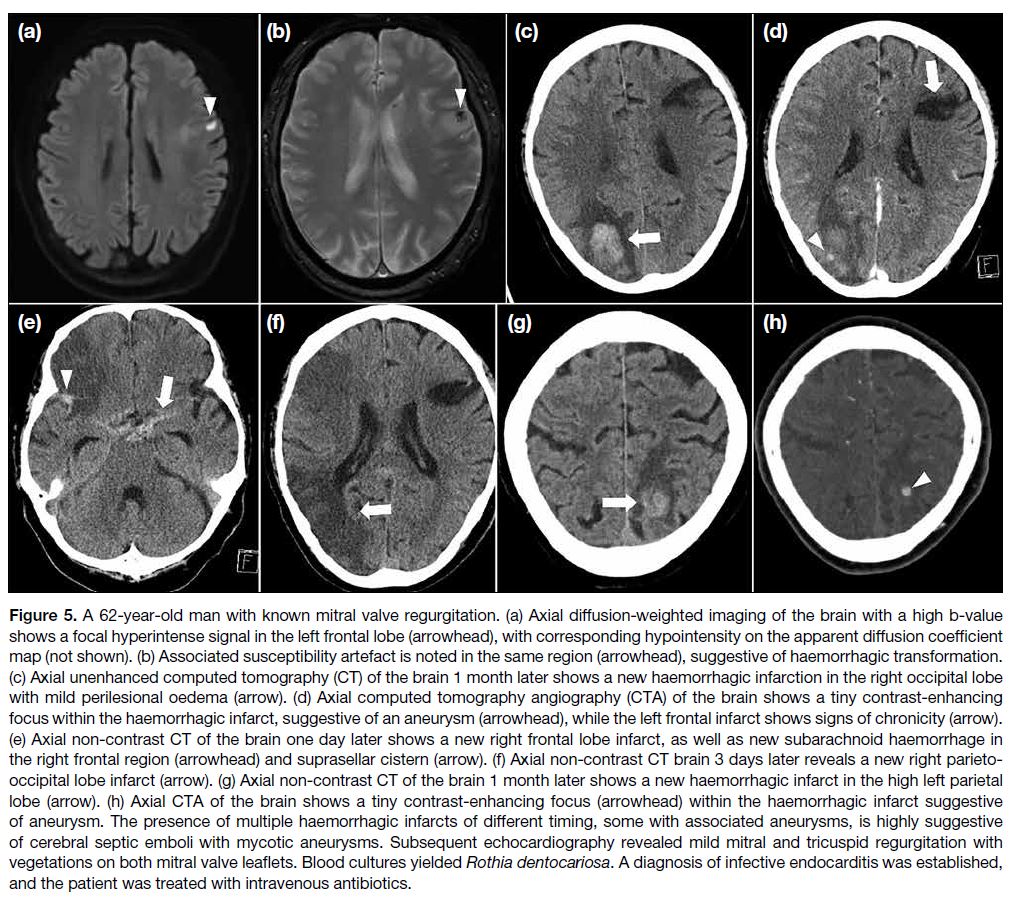

Figure 5. A 62-year-old man with known mitral valve regurgitation. (a) Axial diffusion-weighted imaging of the brain with a high b-value

shows a focal hyperintense signal in the left frontal lobe (arrowhead), with corresponding hypointensity on the apparent diffusion coefficient

map (not shown). (b) Associated susceptibility artefact is noted in the same region (arrowhead), suggestive of haemorrhagic transformation.

(c) Axial unenhanced computed tomography (CT) of the brain 1 month later shows a new haemorrhagic infarction in the right occipital lobe

with mild perilesional oedema (arrow). (d) Axial computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the brain shows a tiny contrast-enhancing

focus within the haemorrhagic infarct, suggestive of an aneurysm (arrowhead), while the left frontal infarct shows signs of chronicity (arrow).

(e) Axial non-contrast CT of the brain one day later shows a new right frontal lobe infarct, as well as new subarachnoid haemorrhage in

the right frontal region (arrowhead) and suprasellar cistern (arrow). (f) Axial non-contrast CT brain 3 days later reveals a new right parieto-occipital

lobe infarct (arrow). (g) Axial non-contrast CT of the brain 1 month later shows a new haemorrhagic infarct in the high left parietal

lobe (arrow). (h) Axial CTA of the brain shows a tiny contrast-enhancing focus (arrowhead) within the haemorrhagic infarct suggestive

of aneurysm. The presence of multiple haemorrhagic infarcts of different timing, some with associated aneurysms, is highly suggestive

of cerebral septic emboli with mycotic aneurysms. Subsequent echocardiography revealed mild mitral and tricuspid regurgitation with

vegetations on both mitral valve leaflets. Blood cultures yielded Rothia dentocariosa. A diagnosis of infective endocarditis was established,

and the patient was treated with intravenous antibiotics.

Mycotic Aneurysms

Cerebral septic emboli can trigger inflammation and

weakening of vessel walls, forming mycotic aneurysms.[7] These aneurysms are found in about 6.2% of patients with

IE and may shrink, enlarge, or develop de novo within

1 week to 3 months of starting antibiotics.[12] Mycotic

aneurysms have a 2% to 10% risk of rupture regardless

of their size and are associated with a high mortality

rate of 80%.[7] About 22% of IE patients presenting with

intracerebral haemorrhage have mycotic aneurysms

which should be promptly identified.[13] CTA or MRA

should be performed to confirm the diagnosis (Figures 5 and 6), followed by DSA for clear delineation of the

number, size and location of the mycotic aneurysms and

surgical or endovascular planning.

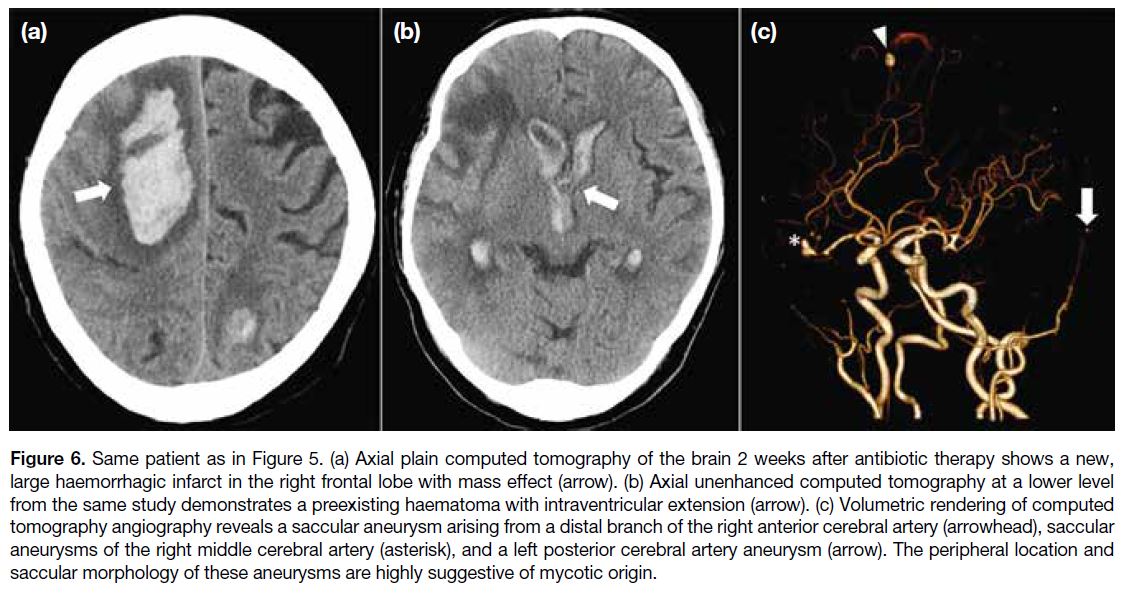

Figure 6. Same patient as in Figure 5. (a) Axial plain computed tomography of the brain 2 weeks after antibiotic therapy shows a new,

large haemorrhagic infarct in the right frontal lobe with mass effect (arrow). (b) Axial unenhanced computed tomography at a lower level

from the same study demonstrates a preexisting haematoma with intraventricular extension (arrow). (c) Volumetric rendering of computed

tomography angiography reveals a saccular aneurysm arising from a distal branch of the right anterior cerebral artery (arrowhead), saccular

aneurysms of the right middle cerebral artery (asterisk), and a left posterior cerebral artery aneurysm (arrow). The peripheral location and

saccular morphology of these aneurysms are highly suggestive of mycotic origin.

CTA and MRA have low sensitivity for small (<5 mm)

or distal mycotic aneurysms.[1] Aneurysms near the skull

base may be overlooked on CTA, while those in low-flow

areas may be missed on time-of-flight MRA.[14] In

cases with clinical suspicion of mycotic aneurysm but

negative CTA or MRA, DSA should be performed.[1]

Features favouring mycotic aneurysms include

multiplicity, saccular shape, distal location (such as

MCA segments 2 to 4 or posterior cerebral artery), size

or morphological changes on consecutive angiograms,

presence of other intra- or extra-cranial mycotic

aneurysms, adjacent arterial occlusion or stenosis, and

cerebral infarction at the aneurysm site[13] (Figure 6).

Management

Neurological complications from IE are life-threatening

and require multidisciplinary management, involving

neurosurgeons, radiologists, cardiologists, and

microbiologists. Empirical intravenous antibiotic therapy

is promptly administered and later tailored according

to culture sensitivity results. Valvular replacement

combined with antibiotics yield better outcomes than

antibiotics alone in left-sided endocarditis.[15]

Radiologists play a key role in both diagnosis and guiding

treatment by accurately reporting the type and severity

of each lesion. Surgical drainage can be considered in

cases of cerebral abscesses with significant mass effect.

Antiplatelet drugs and anticoagulants are contraindicated in both ischaemic stroke and macrohaemorrhage caused

by septic embolism due to the high risk of bleeding.[3]

Cardiac surgery should be postponed for at least 4 weeks

after a clinically significant intracranial haemorrhage

or large ischaemic infarct.[3] Mycotic aneurysms should

be excluded before open heart surgery for valvular

replacement requiring anticoagulation to reduce bleeding

risk.[15]

Interventional radiologists play an evolving role of

in treating mycotic aneurysms in collaboration with

neurosurgeons. Techniques include preoperative CTA or

MRA with volumetric rendering, road-map technique for

neuro-navigation, and cone-beam CTA for postprocedural

monitoring. Given the unpredictable nature of mycotic aneurysms and the weak correlation between size and

rupture risk, surgical or endovascular treatment should

be considered for unruptured aneurysms that enlarge

or do not regress on follow-up imaging.[7] [14] Ruptured or

symptomatic mycotic aneurysms also require surgical

or endovascular intervention.[14] A surgical approach

is indicated when an aneurysm exerts mass effect[14] or

supplies an eloquent brain region.[1] However, clipping

may be difficult due to a wide or absent aneurysmal neck

and fragile vessels.[3]

An endovascular approach is indicated for those unfit for

surgery due to cardiac disease.[3] It can be divided into

direct or indirect approaches. An indirect approach with

parent artery occlusion is the endovascular treatment of

choice, especially for distally located aneurysms and

circumferential vessel involvement. However, parent

artery sacrifice is not possible at times and the direct

approach may remain the only viable option. The direct approach using coils or liquid embolic agents allows

precise control of the aneurysm while preserving distal

flow from the parent artery. Endovascular coiling may be

a safer option with higher occlusion and lower procedure-related

complication rates[7] (Figure 7). Detachable

coils allow precise deployment and better durability

compared with liquid embolic agents. They are preferred

in proximal aneurysms, while liquid embolic agents

are more suitable for distal aneurysms not accessible

by microcatheter. Intracranial flow diverters can be

used to divert turbulent blood flow from the aneurysm

and preserve laminar blood flow in the main vessel

and its side branches. With reduced blood flow to the

aneurysm and gradual vessel remodelling, this results

in progressive aneurysmal sac thrombosis[16] (Figure 8). It is important to note that mycotic aneurysms may

grow after simple coiling, while the parent artery may

thrombose after flow diverter placement in the setting

of infection.

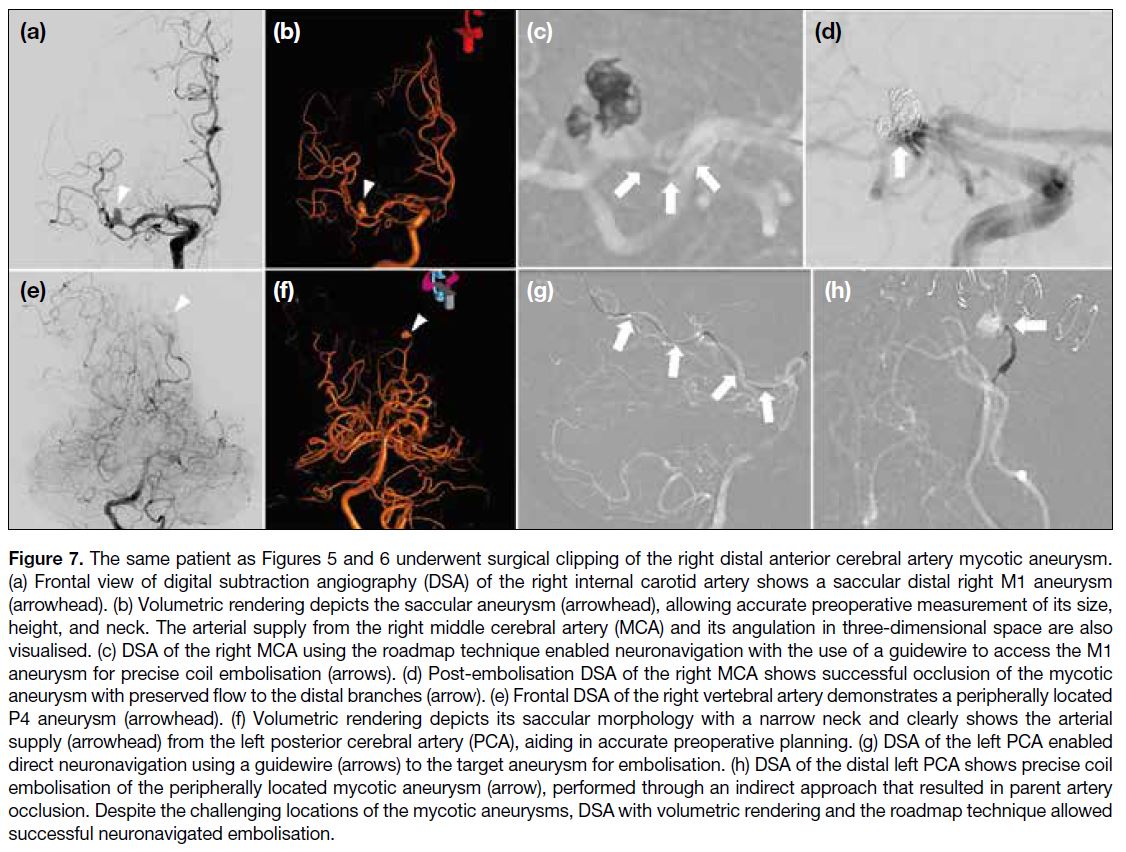

Figure 7. The same patient as Figures 5 and 6 underwent surgical clipping of the right distal anterior cerebral artery mycotic aneurysm.

(a) Frontal view of digital subtraction angiography (DSA) of the right internal carotid artery shows a saccular distal right M1 aneurysm

(arrowhead). (b) Volumetric rendering depicts the saccular aneurysm (arrowhead), allowing accurate preoperative measurement of its size,

height, and neck. The arterial supply from the right middle cerebral artery (MCA) and its angulation in three-dimensional space are also

visualised. (c) DSA of the right MCA using the roadmap technique enabled neuronavigation with the use of a guidewire to access the M1

aneurysm for precise coil embolisation (arrows). (d) Post-embolisation DSA of the right MCA shows successful occlusion of the mycotic

aneurysm with preserved flow to the distal branches (arrow). (e) Frontal DSA of the right vertebral artery demonstrates a peripherally located

P4 aneurysm (arrowhead). (f) Volumetric rendering depicts its saccular morphology with a narrow neck and clearly shows the arterial

supply (arrowhead) from the left posterior cerebral artery (PCA), aiding in accurate preoperative planning. (g) DSA of the left PCA enabled

direct neuronavigation using a guidewire (arrows) to the target aneurysm for embolisation. (h) DSA of the distal left PCA shows precise coil

embolisation of the peripherally located mycotic aneurysm (arrow), performed through an indirect approach that resulted in parent artery

occlusion. Despite the challenging locations of the mycotic aneurysms, DSA with volumetric rendering and the roadmap technique allowed

successful neuronavigated embolisation.

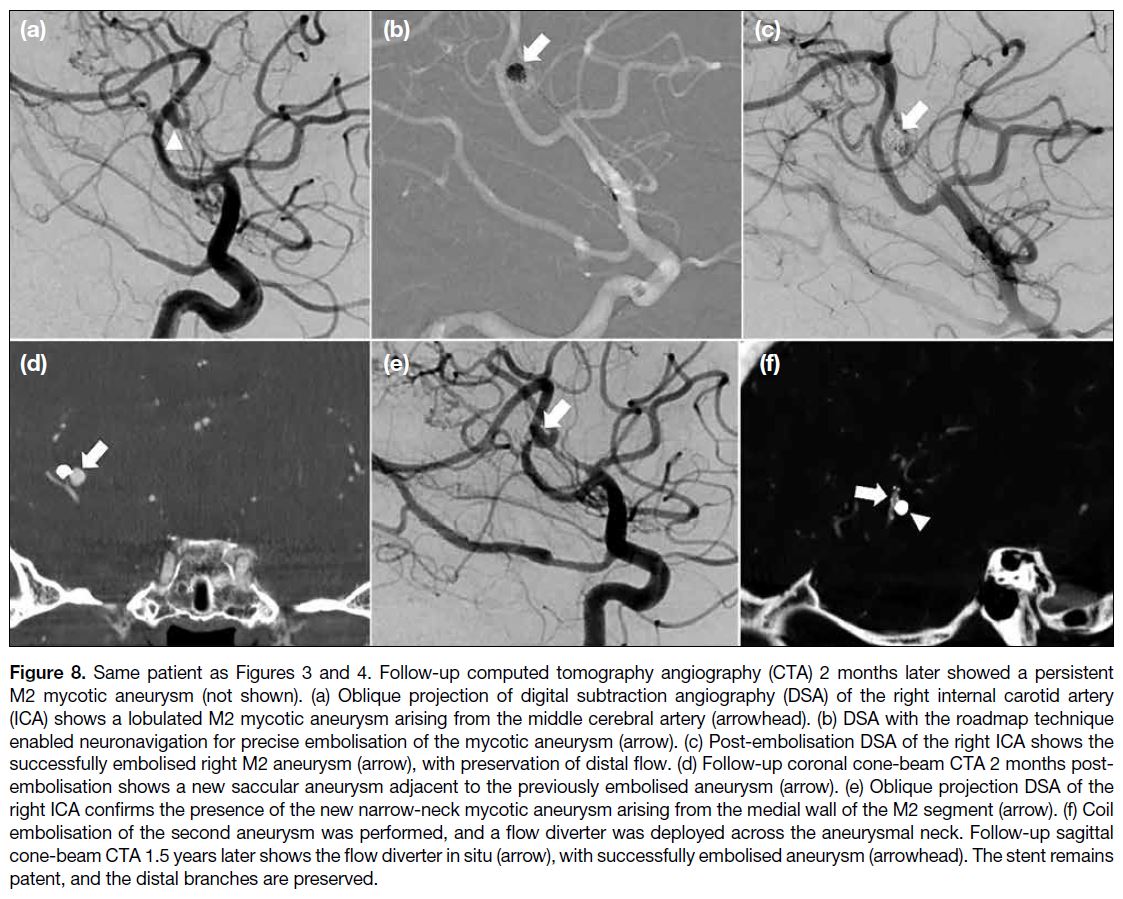

Figure 8. Same patient as Figures 3 and 4. Follow-up computed tomography angiography (CTA) 2 months later showed a persistent

M2 mycotic aneurysm (not shown). (a) Oblique projection of digital subtraction angiography (DSA) of the right internal carotid artery

(ICA) shows a lobulated M2 mycotic aneurysm arising from the middle cerebral artery (arrowhead). (b) DSA with the roadmap technique

enabled neuronavigation for precise embolisation of the mycotic aneurysm (arrow). (c) Post-embolisation DSA of the right ICA shows the

successfully embolised right M2 aneurysm (arrow), with preservation of distal flow. (d) Follow-up coronal cone-beam CTA 2 months post-embolisation

shows a new saccular aneurysm adjacent to the previously embolised aneurysm (arrow). (e) Oblique projection DSA of the

right ICA confirms the presence of the new narrow-neck mycotic aneurysm arising from the medial wall of the M2 segment (arrow). (f) Coil

embolisation of the second aneurysm was performed, and a flow diverter was deployed across the aneurysmal neck. Follow-up sagittal

cone-beam CTA 1.5 years later shows the flow diverter in situ (arrow), with successfully embolised aneurysm (arrowhead). The stent remains

patent, and the distal branches are preserved.

CONCLUSION

Neurological complications secondary to IE require

prompt recognition of its typical presentations and

imaging manifestations to facilitate early diagnosis

of neurological complications and their subsequent

treatment, including possible radiological intervention.

REFERENCES

1. Ferro JM, Fonseca AC. Infective endocarditis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;119:75-91. Crossref

2. Papadimitriou-Olivgeris M, Guery B, Ianculescu N, Dunet V,

Messaoudi Y, Pistocchi S, et al. Role of cerebral imaging on

diagnosis and management in patients with suspected infective

endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;77:371-9. Crossref

3. Morris NA, Matiello M, Lyons JL, Samuels MA. Neurologic

complications in infective endocarditis: identification, management,

and impact on cardiac surgery. Neurohospitalist. 2014;4:213-22. Crossref

4. Hess A, Klein I, Iung B, Lavallée P, Ilic-Habensus E, Dornic Q, et al.

Brain MRI findings in neurologically asymptomatic patients with

infective endocarditis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:1579-84. Crossref

5. Duval X, Iung B, Klein I, Brochet E, Thabut G, Arnoult F, et al.

Effect of early cerebral magnetic resonance imaging on clinical

decisions in infective endocarditis: a prospective study. Ann Intern

Med. 2010;152:497-504, W175. Crossref

6. Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP,

Del Zotti F, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of

infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of

Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology

(ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic

Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine

(EANM). Eur Heart J. 2015;36:3075-128. Crossref

7. Zanaty M, Chalouhi N, Starke RM, Tjoumakaris S, Gonzalez LF, Hasan D, et al. Endovascular treatment of cerebral mycotic

aneurysm: a review of the literature and single center experience.

Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:151643. Crossref

8. Ahn Y, Joo L, Suh CH, Kim S, Shim WH, Kim SJ, et al. Impact

of brain MRI on the diagnosis of infective endocarditis and

treatment decisions: systematic review and meta-analysis. AJR

Am J Roentgenol. 2022;218:958-68. Crossref

9. Zakhari N, Castillo M, Torres C. Unusual cerebral emboli. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2016;26:147-63. Crossref

10. Allen LM, Hasso AN, Handwerker J, Farid H. Sequence-specific

MR imaging findings that are useful in dating ischemic stroke.

Radiographics. 2012;32:1285-97. Crossref

11. Cho IJ, Kim JS, Chang HJ, Kim YJ, Lee SC, Choi JH, et al.

Prediction of hemorrhagic transformation following embolic

stroke in patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis. J Cardiovasc

Ultrasound. 2013;21:123-9. Crossref

12. Chapot R, Houdart E, Saint-Maurice JP, Aymard A, Mounayer C, Lot G, et al. Endovascular treatment of cerebral mycotic aneurysms.

Radiology. 2002;222:389-96. Crossref

13. Hui FK, Bain M, Obuchowski NA, Gordon S, Spiotta AM,

Moskowitz S, et al. Mycotic aneurysm detection rates with cerebral

angiography in patients with infective endocarditis. J Neurointerv

Surg. 2015;7:449-52. Crossref

14. Kannoth S, Thomas SV. Intracranial microbial aneurysm (infectious

aneurysm): current options for diagnosis and management.

Neurocrit Care. 2009;11:120-9. Crossref

15. Heiro M, Nikoskelainen J, Engblom E, Kotilainen E, Marttila R,

Kotilainen P. Neurologic manifestations of infective endocarditis:

a 17-year experience in a teaching hospital in Finland. Arch Intern

Med. 2000;160:2781-7. Crossref

16. Ravindran K, Casabella AM, Cebral J, Brinjikji W, Kallmes DF,

Kadirvel R. Mechanism of action and biology of flow diverters

in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery.

2020;86(Suppl 1):S13-9. Crossref