Vascular Abnormalities in the Breast: A Pictorial Essay

PICTORIAL ESSAY

Hong Kong J Radiol 2025;28:Epub 10 December 2025

Vascular Abnormalities in the Breast: A Pictorial Essay

SH Lee, S Yang, GHC Wong

Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr SH Lee, Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: lsh689@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 15 October 2024; Accepted: 5 February 2025. This version may differ from the final version when published in an issue.

Contributors: SHL designed the study. SHL and GHCW acquired the data. SHL and SY analysed the data. SHL draft the manuscript. SY

critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the

final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Central Institutional Review Board of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: CIRB-2024-186-2). A waiver of patient consent and acknowledgment forms was approved by the Board due to the retrospective nature of the study.

INTRODUCTION

Vascular lesions are not uncommonly seen in the

breast. They can range from benign haemangiomas

to aggressive angiosarcomas. Benign lesions and

vascular malformations are usually asymptomatic when

small in size and may only be incidentally found on

imaging. Malignant angiosarcomas are extremely rare

and aggressive, often presenting with disseminated

metastases on diagnosis. This pictorial essay aims to

illustrate the common imaging features of vascular

lesions, with the cases identified in the database of a

local tertiary hospital in Hong Kong from 2008 to 2024.

BENIGN VASCULAR LESIONS

Haemangioma

Haemangiomas are commonly found in the hepatobiliary

and musculoskeletal systems, as well as in the breasts,

where they are usually small in size and asymptomatic,

usually presenting as an incidental imaging finding. It

has been reported that haemangiomas are found in 1.2%

of mastectomy specimens and 11% of post-mortem

specimens (from a forensic population) of the female

breast.[1] Some patients might present with blue skin

discolouration when the lesion is large and superficial.

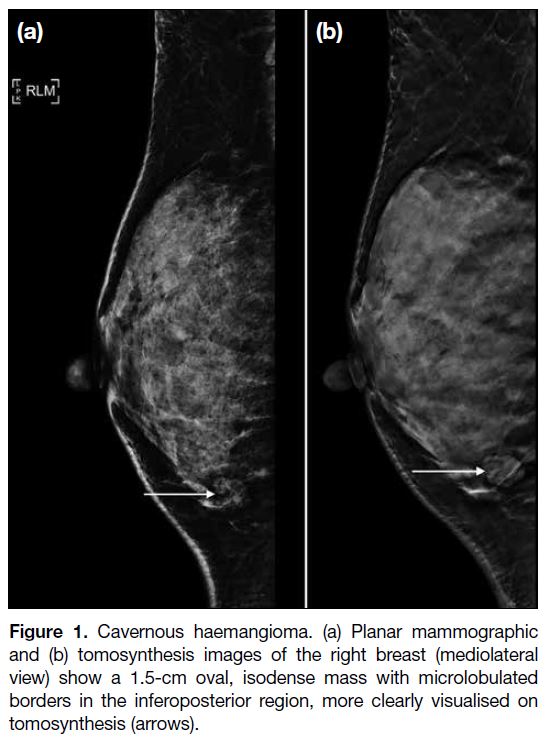

On mammography, haemangiomas are usually equal

dense to the breast tissue, and oval in shape with

circumscribed or microlobulated margins (Figure 1).[2] Intralesional microcalcifications may be found

occasionally[2], which may lead to the need for imaging

surveillance or core biopsy.

Figure 1. Cavernous haemangioma. (a) Planar mammographic

and (b) tomosynthesis images of the right breast (mediolateral

view) show a 1.5-cm oval, isodense mass with microlobulated

borders in the inferoposterior region, more clearly visualised on

tomosynthesis (arrows).

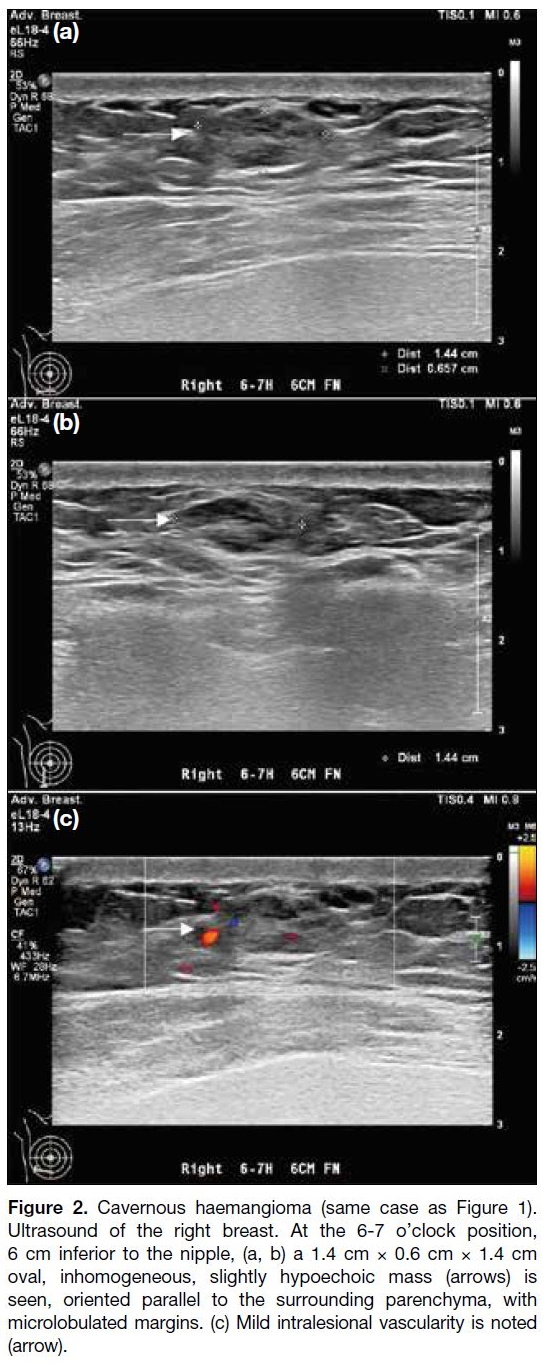

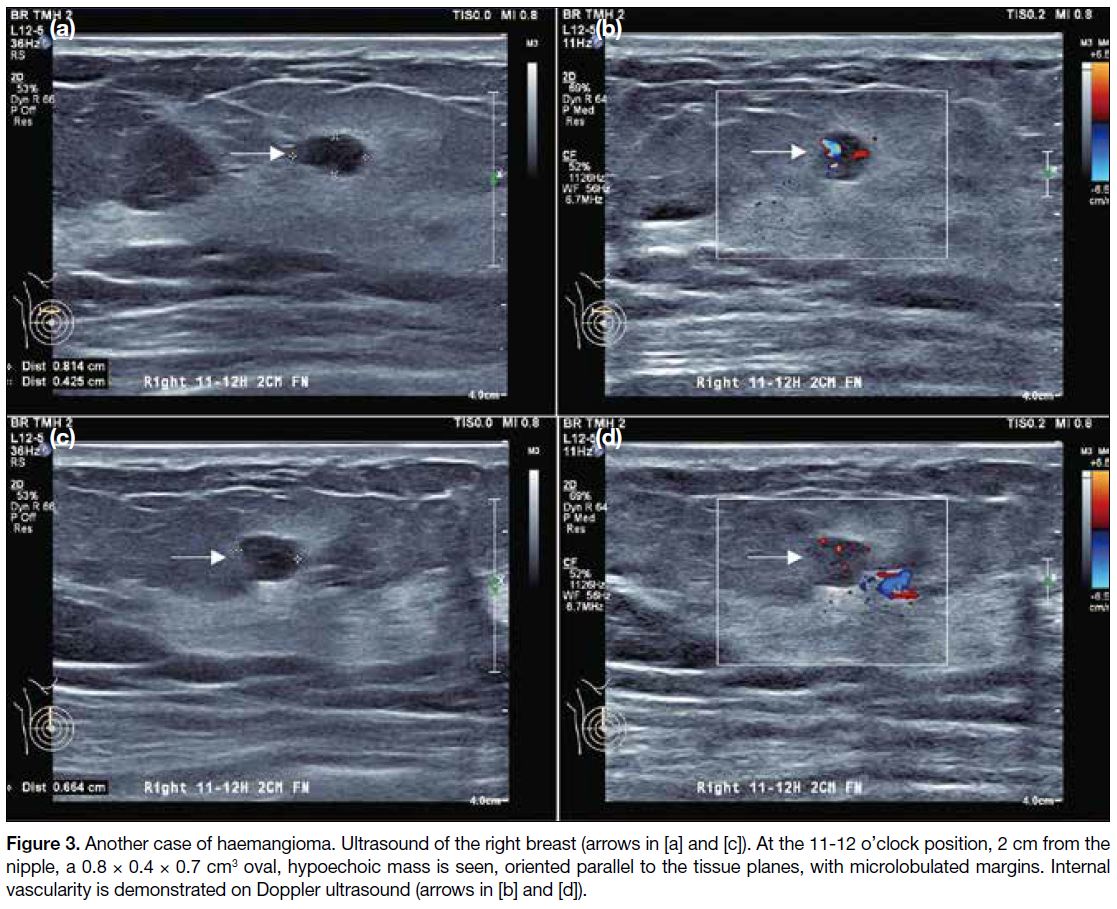

Sonographically, they are similar to their shape on

mammography and are oriented in a parallel manner

(Figures 2 and 3).[2] Their echogenicity is variable,[2] and

they may exhibit non-specific vascular flow.[3] Overall,

there are no definitive imaging features to suggest

benignity or malignancy. Histologically, these lesions

may present as a proliferation of variably sized, ectatic

blood vessels separated by fibrotic stroma.

Figure 2. Cavernous haemangioma (same case as Figure 1). Ultrasound of the right breast. At the 6-7 o’clock position, 6 cm inferior to the nipple, (a, b) a 1.4 cm × 0.6 cm × 1.4 cm oval, inhomogeneous, slightly hypoechoic mass (arrows) is seen, oriented parallel to the surrounding parenchyma, with microlobulated margins. (c) Mild intralesional vascularity is noted (arrow).

Figure 3. Another case of haemangioma. Ultrasound of the right breast arrows in [a] and [c]. At the 11-12 o’clock position, 2 cm from the nipple, a 0.8

× 0.4 × 0.7 cm3 oval, hypoechoic mass is seen, oriented parallel to the tissue planes, with microlobulated margins. Internal vascularity is

demonstrated on Doppler ultrasound (arrows in [b] and [d]).

Management of benign haemangiomas remains

controversial due to the sampling error of core biopsy

samples and difficulty in clearly delineating the borders

of the haemangiomas confidently on core samples. A

recent review had explored the possibility of clinical

and radiological surveillance in cases of radiologically

pathologically concordant haemangiomas, but surgical

excision remains the mainstay of management.[4]

Superficial Venous Thrombophlebitis:

Mondor’s Disease

Mondor’s disease is a rare disease characterised by

inflammation and thrombosis of the superficial venous

structures in the breast. This disease is found in less

than 1% of the population.[5] Clinically, patients present

with skin swelling or tender cord-like palpable masses.

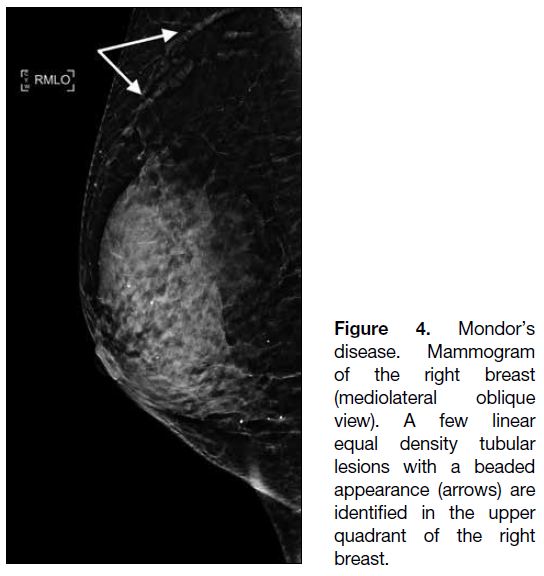

On mammography, elongated equal density tubular

structures are usually found in the upper outer quadrant

where the lateral thoracic veins are located (Figure 4).[6]

Ultrasound should be performed to exclude underlying

breast malignancy since dilated ducts could mimic

Mondor’s disease mammographically.[6]

Figure 4. Mondor’s

disease. Mammogram

of the right breast

(mediolateral oblique

view). A few linear

equal density tubular

lesions with a beaded

appearance (arrows) are

identified in the upper

quadrant of the right

breast.

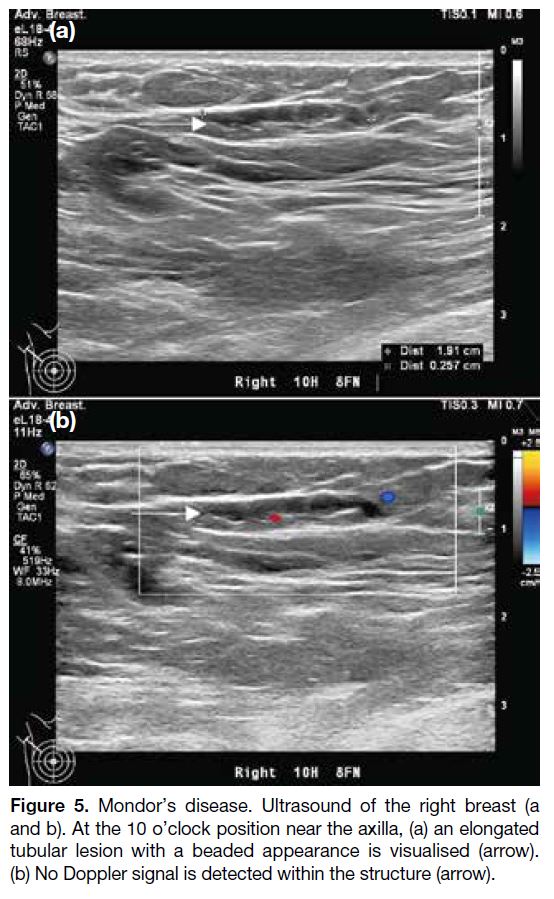

On ultrasound, Mondor’s disease is seen as a tubular

hypoechoic structure with a beaded appearance, which

is the classical finding of a thrombosed vein, but not of

a dilated duct which usually with smooth wall (Figure 5).[6] It is also longer in extent and will not be connected

to the nipple areolar complex.[6] Similar to venous

thrombosis in the body elsewhere, the distended vein is

not compressible by the ultrasound probe and there is

absence of Doppler signal.[5]

Figure 5. Mondor’s disease. Ultrasound of the right breast (a and

b). At the 10 o’clock position near the axilla, (a) an elongated tubular

lesion with a beaded appearance is visualised (arrow). (b) No

Doppler signal is detected within the structure (arrow).

Mondor’s disease does not require a pathological

diagnosis when clinical and radiological findings

are concordant. No specific treatment is needed for

the disease since it will resolve spontaneously in 1 to 2 months’ time.[5] Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs may be considered in symptomatic cases if not

contraindicated.[5]

VASCULAR MALFORMATIONS

High Flow: Arteriovenous Malformation

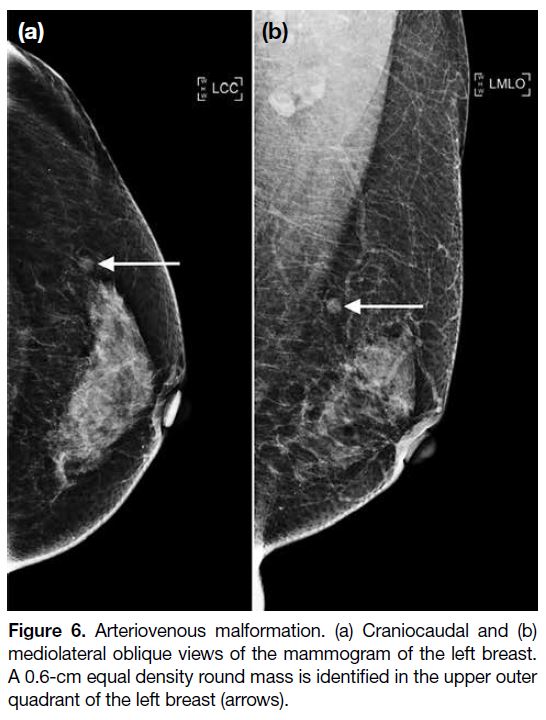

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are exceedingly

rare in the breast, with only scant case reports. No specific

mammographic features are found in AVMs. Similar

to other benign vascular entities, they may present on

mammography as an equal density mass with a round

shape and circumscribed margins (Figure 6). They may

also contain benign-appearing calcifications, indicating

the presence of phleboliths.[7]

Figure 6. Arteriovenous malformation. (a) Craniocaudal and (b)

mediolateral oblique views of the mammogram of the left breast.

A 0.6-cm equal density round mass is identified in the upper outer

quadrant of the left breast (arrows).

On ultrasound, they are again non-specific. In our case,

the lesion presented as an oval heterogeneous hypoechoic

mass with parallel orientation to the skin surface. No

posterior acoustic enhancement was demonstrated. Doppler ultrasound may be a non-invasive technique

to establish the diagnosis since it can demonstrate the

mixture of arterial and venous blood flow within the

lesion (Figure 7).[8]

Figure 7. Arteriovenous malformation. Ultrasound of the left breast. At the 2 o’clock position, 3 cm from the nipple, a 0.6 × 0.4 × 0.5 cm3 oval, heterogeneous, hypoechoic mass is visualised with parallel orientation and no posterior acoustic shadowing. It demonstrates

internal arterial and venous flow, with communication to adjacent breast parenchymal vasculature (arrows).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can demonstrate a

tangle of dilated blood vessels with progressive contrast

enhancement of the lesion.[9] Blooming artefacts indicate

the presence of phleboliths.[9]

The management of AVMs is dependent on the clinical

symptoms. For asymptomatic and small masses, as in our

case, conservative management should be considered. In

case of palpable symptomatic lesions, embolisation or

surgical excision would be the options.[9]

Slow Flow: Venous and Venolymphatic

Malformations

Venous and venolymphatic malformations are slow-flow

vascular lesions, which may be asymptomatic.

Some patients present with bluish skin discolouration

and even with enlarged breast volume when the lesion

is more sizable.

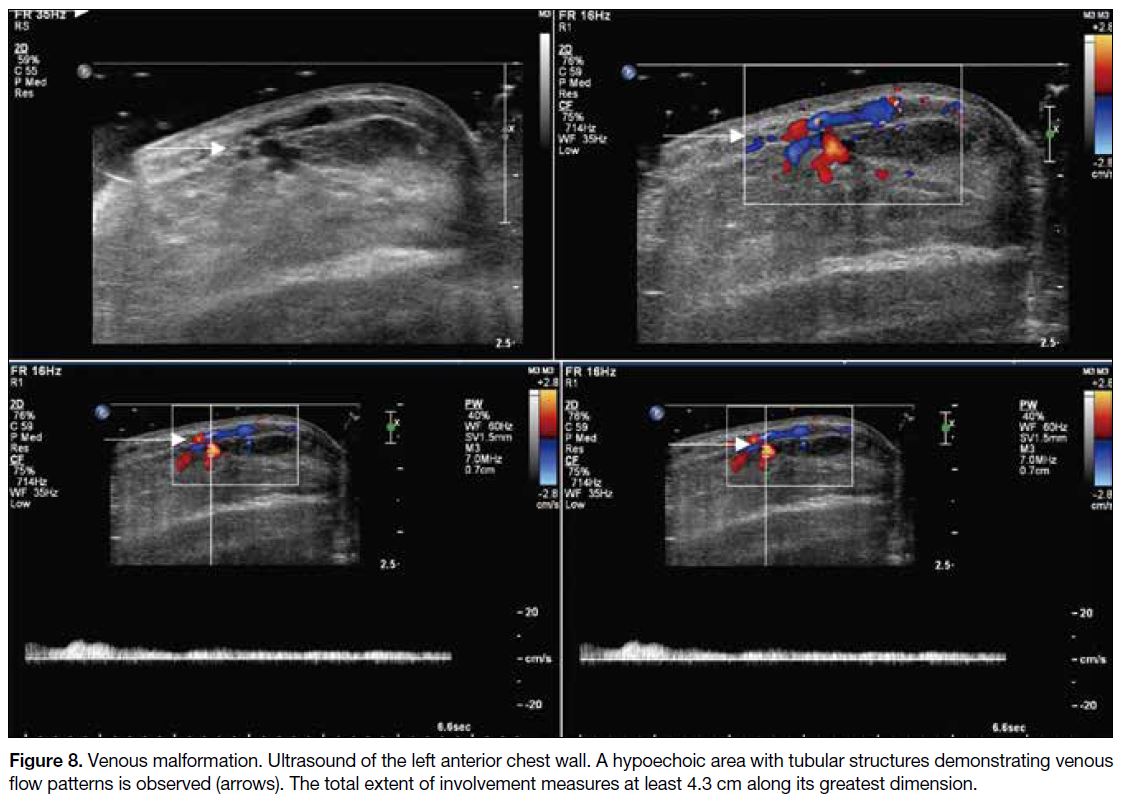

Ultrasound can be a good initial tool to establish the

diagnosis. These lesions are identified as an area of

hypoechogenicity within the breast. Doppler ultrasound

on this hypoechoic area will demonstrate the venous

flow pattern on spectral technique (Figure 8). Other

sonographic findings include echogenic foci indicating

phleboliths and absence of colour uptake due to

thrombosis or lymphatic components.[10]

Figure 8. Venous malformation. Ultrasound of the left anterior chest wall. A hypoechoic area with tubular structures demonstrating

venous flow patterns is observed (arrows). The total extent of involvement measures at least 4.3 cm along its greatest dimension.

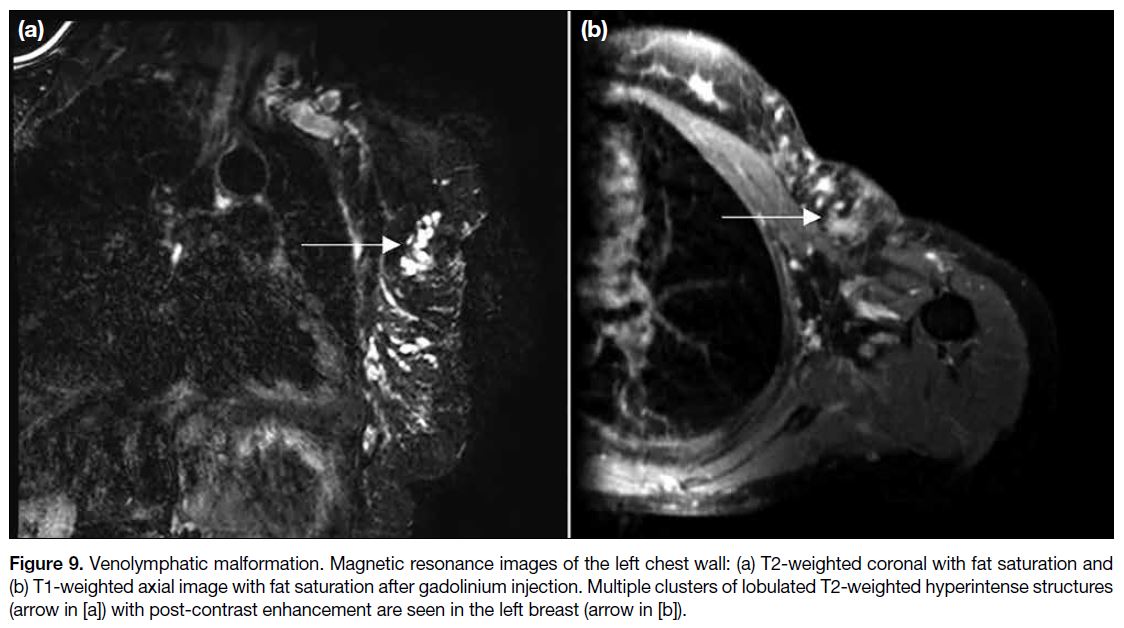

Venous malformations can present as T2-weighted

hyperintense tubular structures. Variable unenhanced

T1-weighted signal has been described depending

on whether these structures contain thrombosis.[10]

Enhancement could be seen on T1-weighted images

after gadolinium injection (Figure 9). If phleboliths

are present, susceptibility artefacts may also be seen.[11]

For the lymphatic component, MRI might demonstrate

septal enhancement in the background of non-enhancing

lymphatic fluid.[12]

Figure 9. Venolymphatic malformation. Magnetic resonance images of the left chest wall: (a) T2-weighted coronal with fat saturation and (b) T1-weighted axial image with fat saturation after gadolinium injection. Multiple clusters of lobulated T2-weighted hyperintense structures (arrow in [a]) with post-contrast enhancement are seen in the left breast (arrow in [b]).

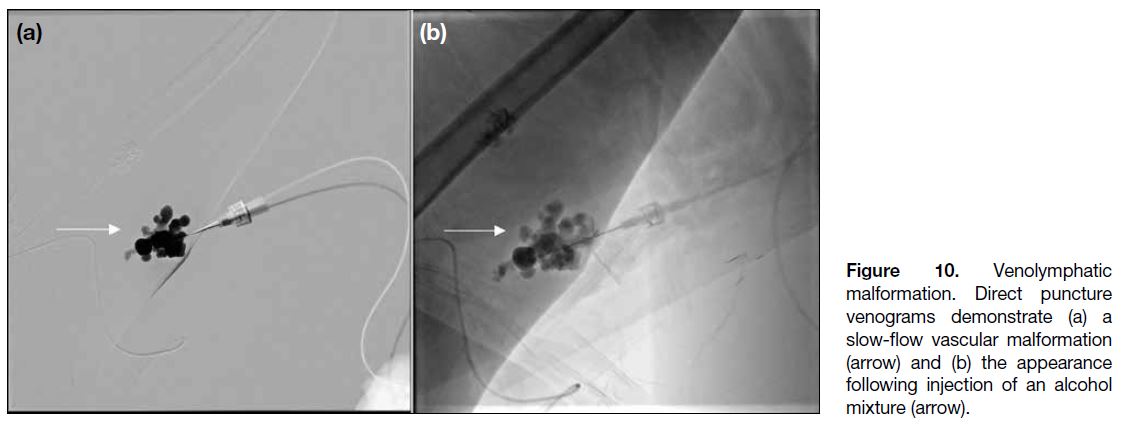

If patients are symptomatic or there is cosmetic concern,

sclerotherapy, laser therapy, or surgical resection

are options.[11] In our case, sclerotherapy with sodium

tetradecyl sulphate foam was performed under the

guidance of direct puncture venography (Figure 10),

with resulting clinical improvement.

Figure 10. Venolymphatic malformation. Direct puncture venograms demonstrate (a) a slow-flow vascular malformation (arrow) and (b) the appearance following injection of an alcohol mixture (arrow).

MALIGNANT VASCULAR LESIONS

Angiosarcoma

Angiosarcoma is an exceedingly rare cause of primary

breast tumour, with the literature-quoted incidence

rate <0.05%.13 There are no specific mammographic

findings.[13]

On ultrasound, they show a variable echogenic pattern,

usually with hypervascularity on Doppler.[13] However,

as mentioned previously, haemangiomas may also

demonstrate hypervascularity, so this feature is not

specific.

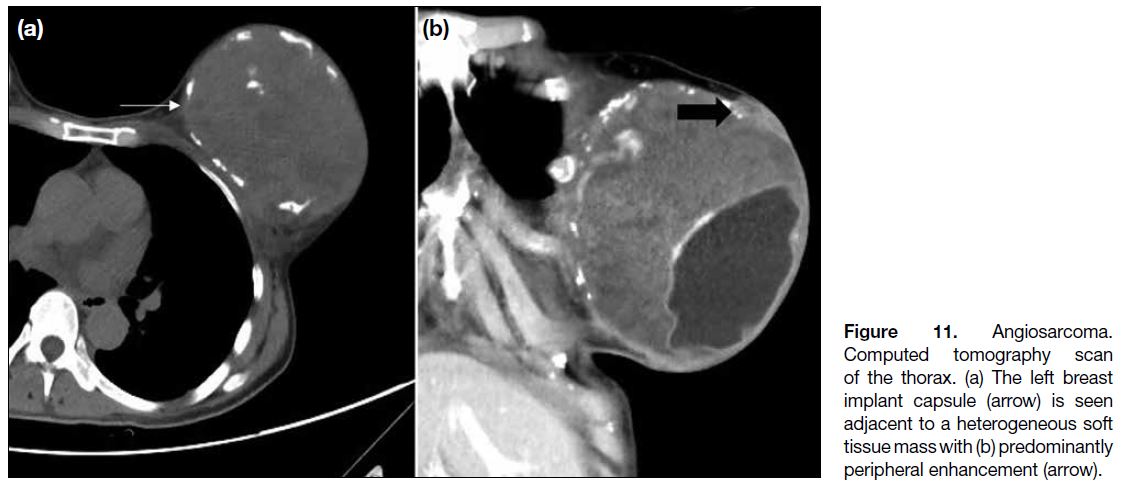

In our case, similar to other breast tumours, angiosarcomas

may enhance after contrast administration on computed

tomography scan (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Angiosarcoma.

Computed tomography scan of

the thorax. (a) The left breast implant

capsule (arrow) is seen

adjacent to a heterogeneous soft

tissue mass with (b) predominantly

peripheral enhancement (arrow).

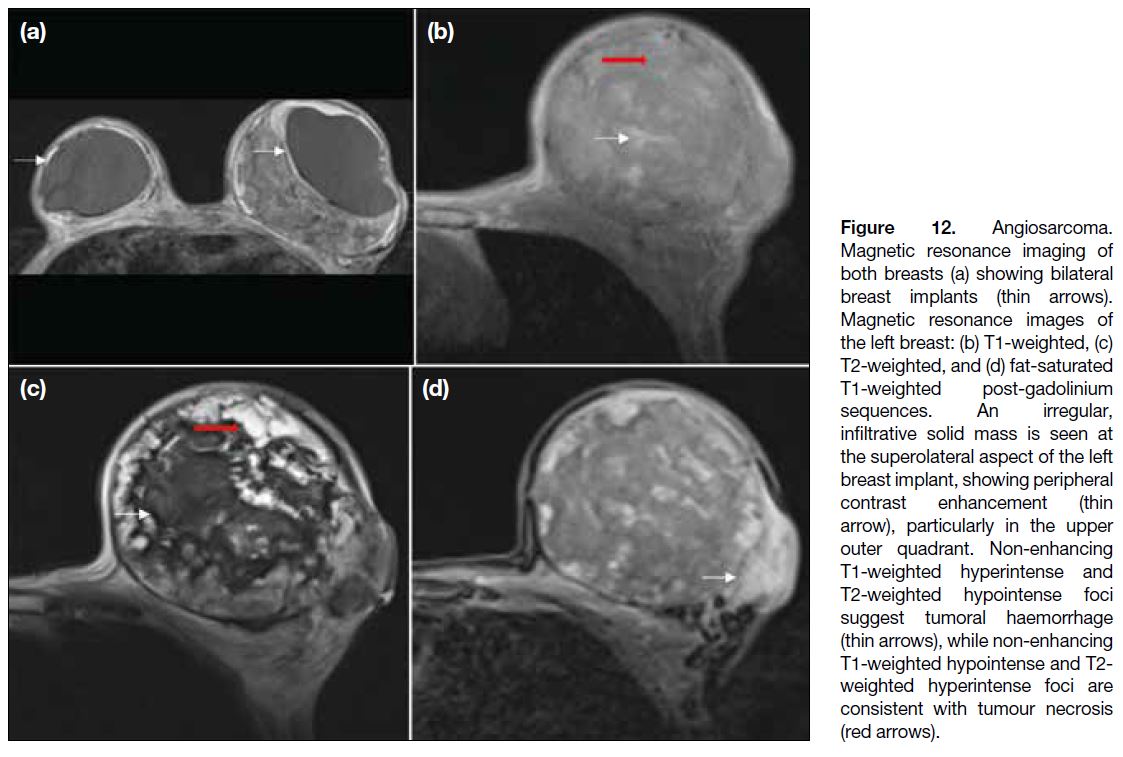

On MRI scan, they showed variable signal intensity

on T1-weighted and T2-weighted images. High T1-weighted signal suggests the presence of haemorrhagic

products or venous lakes.[13] Elevated T2-weighted signals indicate the aggressiveness of the lesion

with cystic degeneration and tumour necrosis.[14]

They enhance, often at the periphery only, after

gadolinium administration (Figure 12).[14] The kinetic

characteristics of the tumours depend on their

grade.[13]

Figure 12. Angiosarcoma.

Magnetic resonance imaging of

both breasts (a) showing bilateral

breast implants (thin arrows).

Magnetic resonance images of

the left breast: (b) T1-weighted, (c)

T2-weighted, and (d) fat-saturated

T1-weighted post-gadolinium

sequences. An irregular,

infiltrative solid mass is seen at

the superolateral aspect of the left

breast implant, showing peripheral

contrast enhancement (thin

arrow), particularly in the upper

outer quadrant. Non-enhancing

T1-weighted hyperintense and

T2-weighted hypointense foci

suggest tumoral haemorrhage

(thin arrows), while non-enhancing

T1-weighted hypointense and T2-weighted hyperintense foci are

consistent with tumour necrosis

(red arrows).

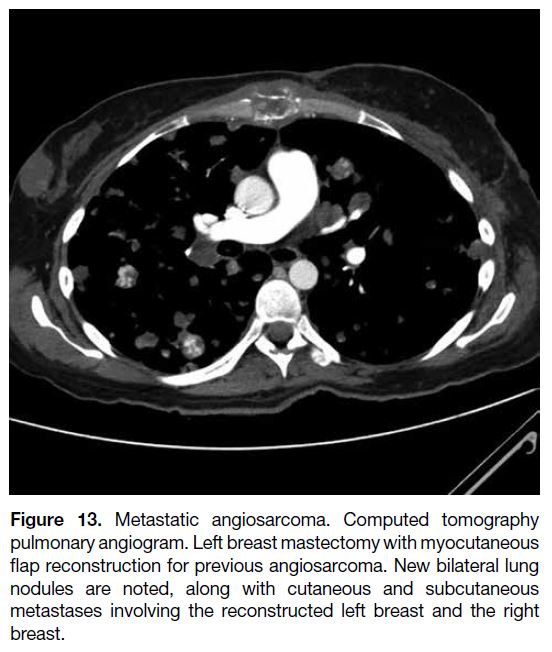

Aggressive surgery remains the mainstay of treatment,

while there is still no consensus on adjuvant treatment.[15]

Angiosarcomas carry a poor prognosis, with the

majority of the cases in our centre showing disseminated

hypervascular metastases or contralateral breast

metastases despite radical surgery performed after

diagnosis (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Metastatic angiosarcoma. Computed tomography

pulmonary angiogram. Left breast mastectomy with myocutaneous

flap reconstruction for previous angiosarcoma. New bilateral lung

nodules are noted, along with cutaneous and subcutaneous

metastases involving the reconstructed left breast and the right

breast.

CONCLUSION

Vascular lesions have been increasingly discovered due

to increased health screening. We should be aware of

the typical imaging features of vascular malformations

to avoid unnecessary biopsies. While histopathological

results are still required to establish the diagnosis in

haemangiomas and angiosarcoma—with surgical

excision remaining the mainstay of management—if the

imaging features of haemangiomas are benign, such as

oval/lobulated shape with well-circumscribed margins,

imaging surveillance could be performed after needle

biopsy.[2]

REFERENCES

1. Kim KM, Kim JY, Kim SH, Jeong MJ, Kim SH, Kim JH,

et al. Breast cavernous hemangioma with increased size on

ultrasonography: a case report. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2018;79:311-4. Crossref

2. Mesurolle B, Sygal V, Lalonde L, Lisbona A, Dufresne MP,

Gagnon JH, et al. Sonographic and mammographic appearances

of breast hemangioma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:W17-22. Crossref

3. Glazebrook KN, Morton MJ, Reynolds C. Vascular tumors of the breast: mammographic, sonographic, and MRI appearances. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:331-8. Crossref

4. Azam R, Mrkonjic M, Gupta A, Gladdy R, Covelli AM.

Mesenchymal tumors of the breast: fibroblastic/myofibroblastic

lesions and other lesions. Curr Oncol. 2023;30:4437-82. Crossref

5. Amano M, Shimizu T. Mondor’s disease: a review of the literature. Intern Med. 2018;57:2607-12. Crossref

6. Shetty MK, Watson AB. Mondor’s disease of the breast: sonographic and mammographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

2001;177:893-6. Crossref

7. Padmanabhan V, Dev B, Garg M, Gnanavel H. Arteriovenous malformation of the breast; report a case. Arch Breast Cancer.

2024;11:96-100. Crossref

8. O’Beirn E, Elliott J, Neary C, McLaughlin R. 32 Congenital arteriovenous malformation of the breast associated with giant

hairy naevus: a case report. Br J Surg. 2021;108(Suppl 6):znab259-64. Crossref

9. Swy E, Wahab R, Mahoney M, Vijapura C. Multimodality imaging review of breast vascular lesions. Clin Radiol. 2022;77:255-63. Crossref

10. Gautam R, Dixit R, Pradhan GS. Venous malformation in the breast: imaging features to avoid unnecessary biopsies or surgery. J Radiol Case Rep. 2023;17:1-8. Crossref

11. Vijapura C, Wahab R. Multiple venous malformations involving

the breast. J Breast Imaging. 2022;4:550-2. Crossref

12. Marín C, J Galindo P, Guzmán F, Ferri B, Parrilla P. Lymphovascular

malformation of the breast: differential diagnosis and a case report

[in English, Spanish]. Cir Esp (Engl Ed). 2019;97:541-3. Crossref

13. Glazebrook KN, Magut MJ, Reynolds C. Angiosarcoma of the breast. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:533-8. Crossref

14. Wu WH, Ji QL, Li ZZ, Wang QN, Liu SY, Yu JF. Mammography and MRI manifestations of breast angiosarcoma. BMC Womens

Health. 2019;19:73. Crossref

15. Bordoni D, Bolletta E, Falco G, Cadenelli P, Rocco N, Tessone A, et al. Primary angiosarcoma of the breast. Int J Surg Case Rep.

2016;20S(Suppl):12-5. Crossref