Intracranial Neuroendocrine Tumour of Unknown Origin Mimicking Neurocysticercosis: A Case Report

CASE REPORT

Hong Kong J Radiol 2025;28:Epub 10 December 2025

Intracranial Neuroendocrine Tumour of Unknown Origin

Mimicking Neurocysticercosis: A Case Report

CW Chan, KO Cheung, CY Cheung

Department of Radiology, North District Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr CW Chan, Department of Radiology, North District Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: ccw147@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 3 December 2024; Accepted: 11 April 2025. This version may differ from the final version when published in an issue.

Contributors: All authors designed the study. CWC acquired and analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised

the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for

publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and provided verbal consent for publication of this case

report, including the accompanying clinical images.

INTRODUCTION

Neuroendocrine tumours of the central nervous system

are relatively rare entities and most cases are metastases.

Primary intracranial neuroendocrine tumour is even rarer,

with fewer than a dozen cases reported worldwide.[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8]

Apart from a case report on a 5-year-old child,[9] all

reported primary cases have been in adults. The location

of lesions reported varies greatly. Reported extra-axial

locations include, but are not limited to, the

cerebellopontine angle, jugular foramen, cavernous

sinus, and skull base. Reported intra-axial locations include the left temporal and parietal lobes, as well as the left

cerebellum. We report a case of neuroendocrine tumour

of unknown origin with multiple intracranial metastases.

CASE PRESENTATION

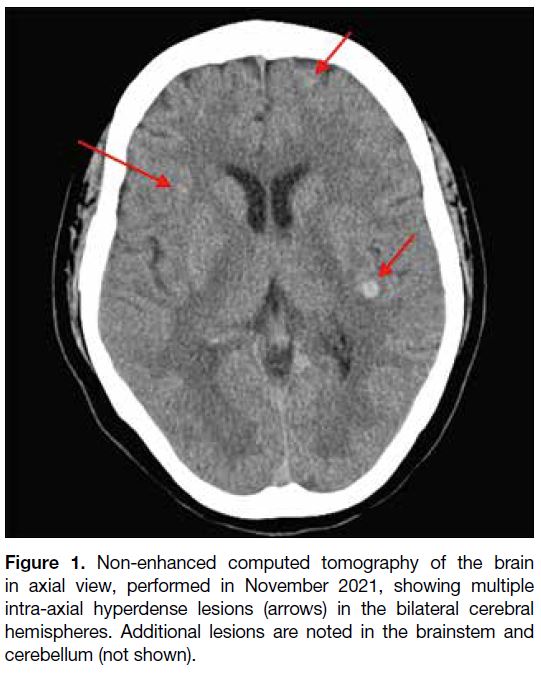

A 56-year-old woman with good past health presented to

the accident and emergency department with dizziness

in October 2021. Initial computed tomography of the

brain revealed multiple hyperdense lesions scattered

across both cerebral hemispheres, the brainstem, and the

cerebellum (Figure 1). Whole-body positron emission

tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) did not reveal any

primary malignancy elsewhere that could suggest brain

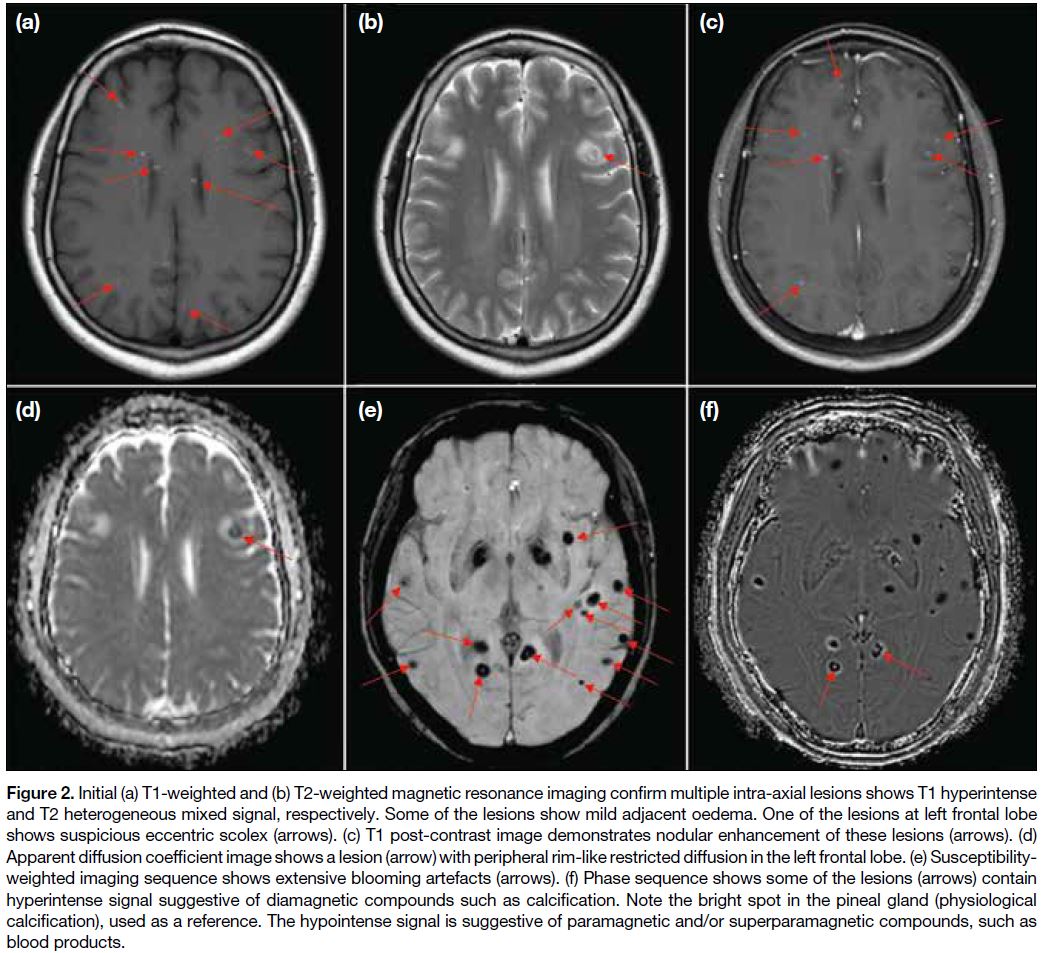

metastases. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) of the brain was performed to

characterise the intracranial lesions (Figure 2). The

corresponding cerebral, brainstem, and cerebellar lesions

showed T1 hyperintense and T2 heterogeneous mixed

signals. Most lesions showed susceptibility artefacts,

while some showed a signal on the phase sequence

characteristic of calcification. Overall features were

suggestive of concurrent haemorrhagic and calcified

lesions. Some lesions also showed eccentric nodular

enhancement. One 7-mm lesion in the left frontal lobe demonstrated restricted diffusion and a suspicious eccentric scolex (Figure 2b). In view of the previously

negative whole-body PET-CT, the possibility of central

nervous system infection with neurocysticercosis in

different stages was considered a likely possibility. A

differential diagnosis of haemorrhagic/calcified brain

metastases appeared less likely. Serology testing for

Taenia solium was negative, but given the radiological

appearance of neurocysticercosis, the patient was

prescribed a course of albendazole and praziquantel, as

well as dexamethasone to minimise cerebral oedema.

Figure 1. Non-enhanced computed tomography of the brain

in axial view, performed in November 2021, showing multiple

intra-axial hyperdense lesions (arrows) in the bilateral cerebral

hemispheres. Additional lesions are noted in the brainstem and

cerebellum (not shown).

Figure 2. Initial (a) T1-weighted and (b) T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging confirm multiple intra-axial lesions shows T1 hyperintense

and T2 heterogeneous mixed signal, respectively. Some of the lesions show mild adjacent oedema. One of the lesions at left frontal lobe

shows suspicious eccentric scolex (arrows). (c) T1 post-contrast image demonstrates nodular enhancement of these lesions (arrows). (d)

Apparent diffusion coefficient image shows a lesion (arrow) with peripheral rim-like restricted diffusion in the left frontal lobe. (e) Susceptibility-weighted

imaging sequence shows extensive blooming artefacts (arrows). (f) Phase sequence shows some of the lesions (arrows) contain

hyperintense signal suggestive of diamagnetic compounds such as calcification. Note the bright spot in the pineal gland (physiological

calcification), used as a reference. The hypointense signal is suggestive of paramagnetic and/or superparamagnetic compounds, such as

blood products.

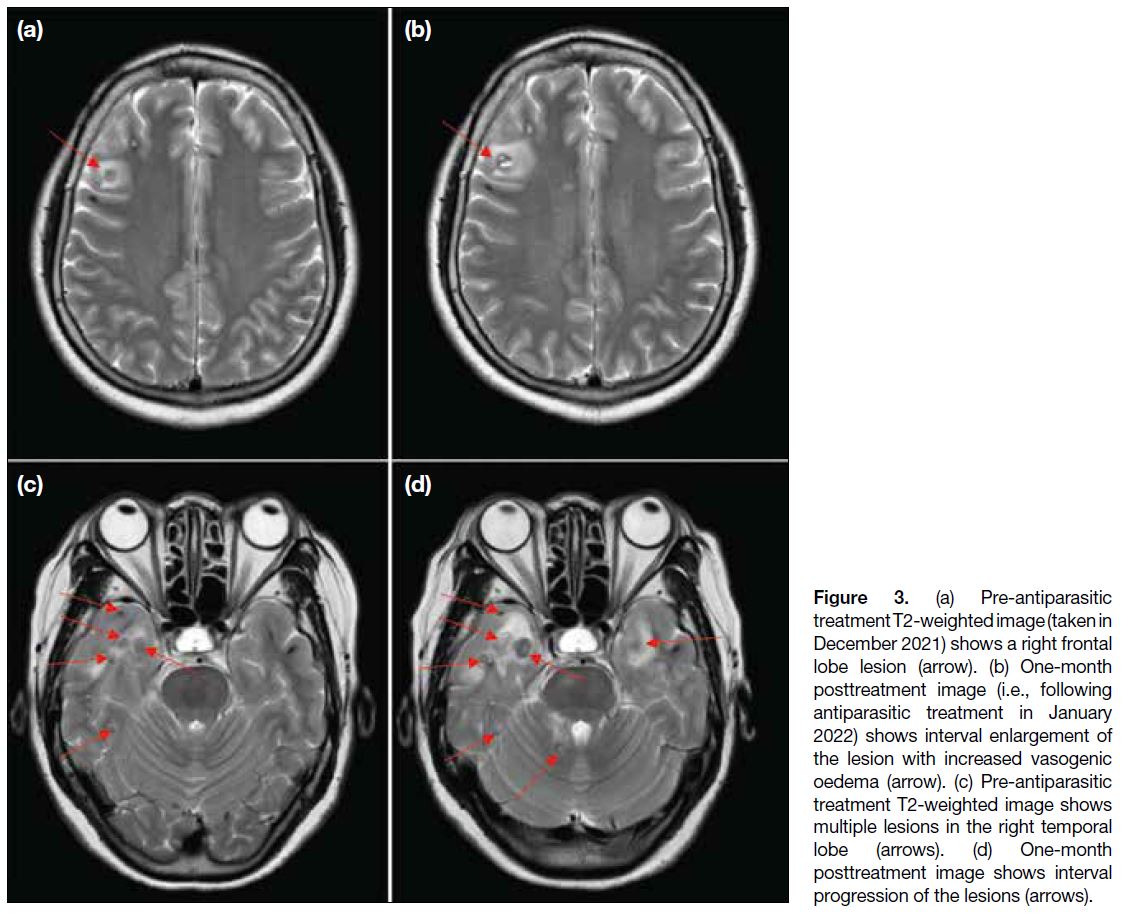

Multiple follow-up MRI scans of the brain were

performed. Initially, at 1-month post-treatment, some

lesions (particularly those at the frontal and temporal lobes) showed interval enlargement with an increase in

perilesional vasogenic oedema (Figure 3). These findings

were thought to be attributable to posttreatment change.

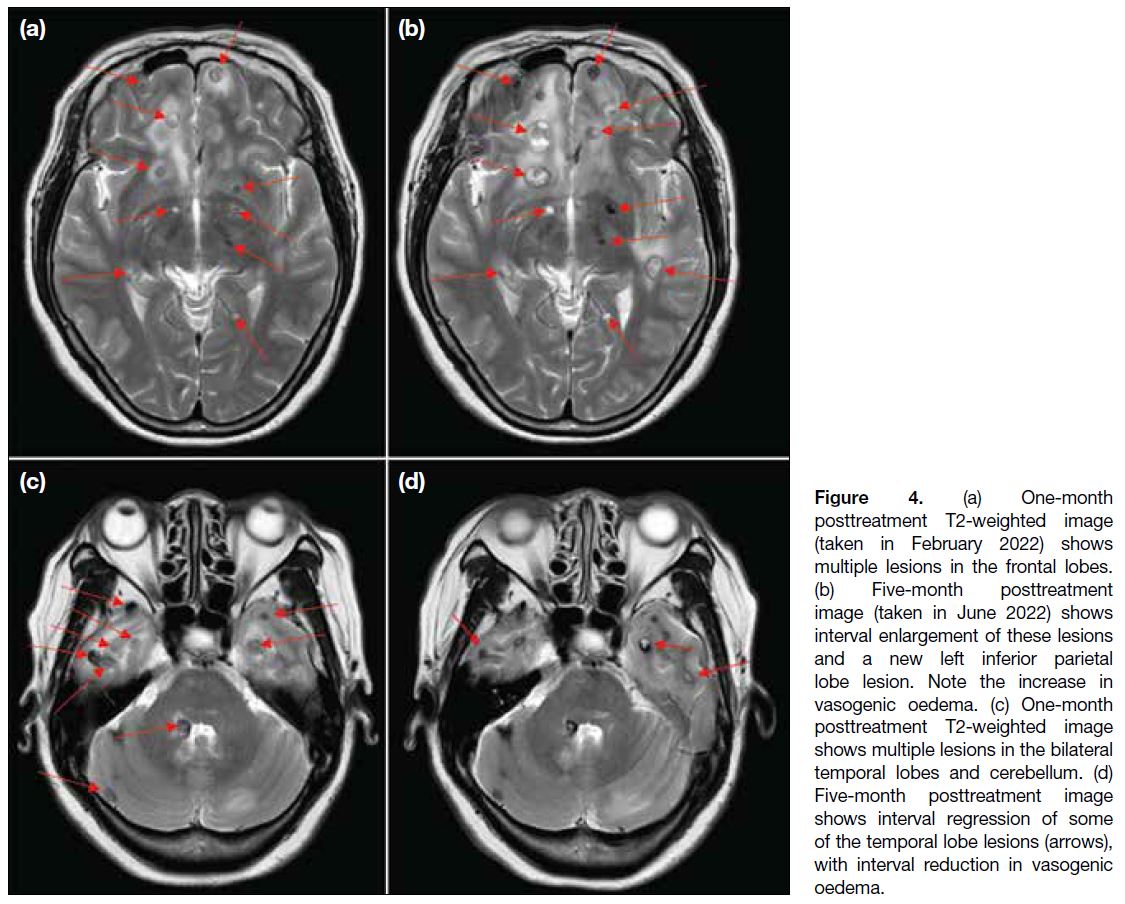

A scan at 5 months posttreatment revealed continued progression of some lesions in the bilateral frontal and left inferior parietal lobes (Figure 4a and b), while some lesions in the bilateral temporal lobes had regressed (Figure 4c and d). The overall picture favoured a mixed treatment response.

Figure 3. (a) Pre-antiparasitic

treatment T2-weighted image (taken in

December 2021) shows a right frontal

lobe lesion (arrow). (b) One-month

posttreatment image (i.e., following

antiparasitic treatment in January

2022) shows interval enlargement of

the lesion with increased vasogenic

oedema (arrow). (c) Pre-antiparasitic

treatment T2-weighted image shows

multiple lesions in the right temporal

lobe (arrows). (d) One-month

posttreatment image shows interval

progression of the lesions (arrows).

Figure 4. (a) One-month

posttreatment T2-weighted image

(taken in February 2022) shows

multiple lesions in the frontal lobes.

(b) Five-month posttreatment

image (taken in June 2022) shows

interval enlargement of these lesions

and a new left inferior parietal

lobe lesion. Note the increase in

vasogenic oedema. (c) One-month

posttreatment T2-weighted image

shows multiple lesions in the bilateral

temporal lobes and cerebellum. (d)

Five-month posttreatment image

shows interval regression of some

of the temporal lobe lesions (arrows),

with interval reduction in vasogenic

oedema.

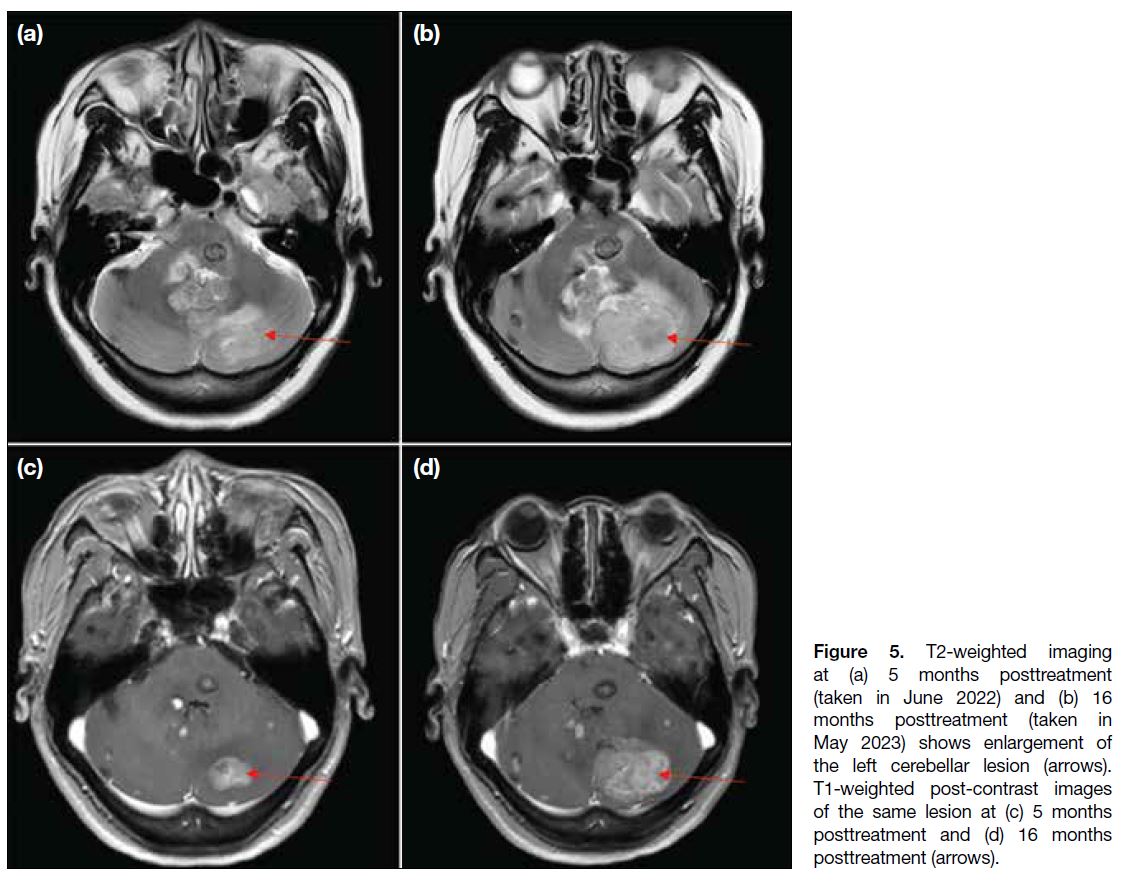

A further course of antiparasitic treatment was given,

assuming the infection was unresolved. Nonetheless,

follow-up scan at 16 months after initiation of antiparasitic

treatment showed not only persistent lesions, but interval

enlargement of some (the largest at the left cerebellar

hemisphere; Figure 5), with developing obstructive

hydrocephalus. In view of the patient’s worsening

symptoms of increased intracranial pressure (headache, dizziness and vomiting), as well as imaging findings,

the neurosurgical team intervened and left posterior

craniotomy was performed for decompression and to

excise the left cerebellar lesion. An external ventricular

drain was placed. Intraoperative findings noted a large

intra-axial tumour at the left cerebellar hemisphere,

likely malignant. Pathology confirmed a grade 3

neuroendocrine tumour, with additional comment that

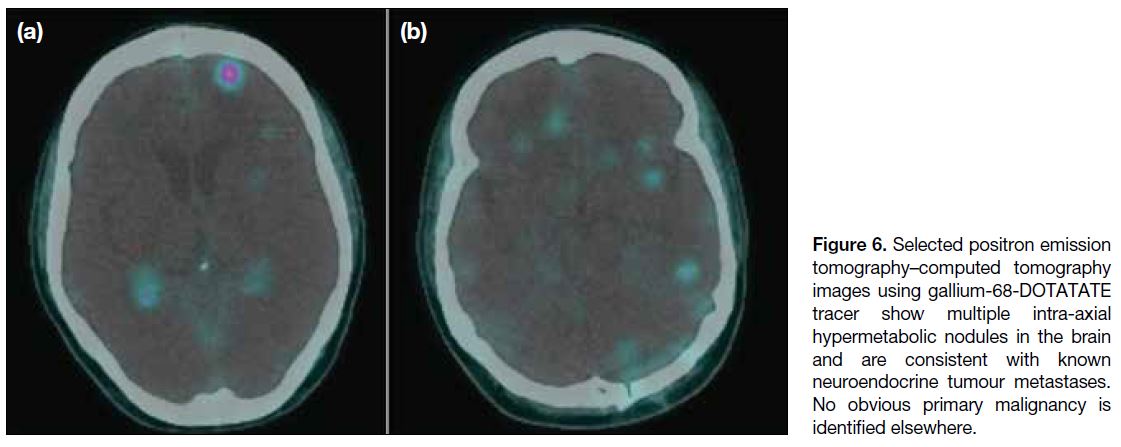

a metastatic lesion was likely. A repeated whole-body

PET-CT with gallium-68-DOTA-tyr3-octreotate (Ga-68-DOTATATE) showed multiple hypermetabolic nodules

in the brain suggestive of known neuroendocrine tumour

(Figure 6), but still no obvious location for a primary

malignancy. A preliminary diagnosis was reached of

neuroendocrine tumour of unknown origin, with possible

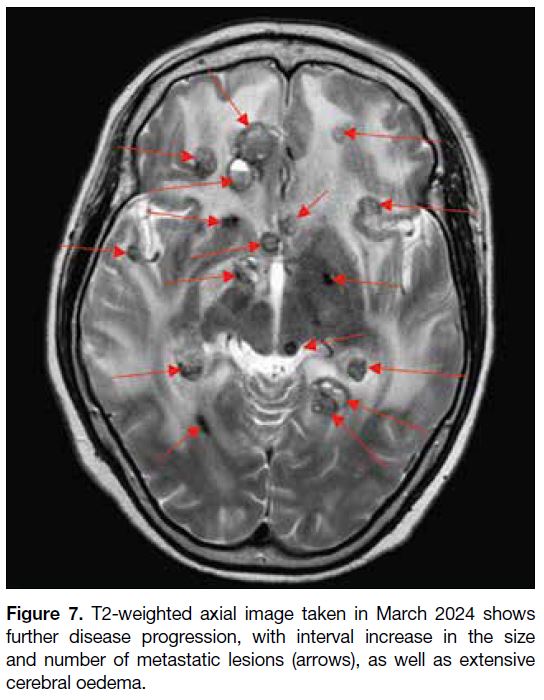

primary within the brain. Postoperatively, the patient

underwent further follow-up MRI scans that revealed

new suspicious drop metastasis at the C4 level, as well as significant progression of brain metastases and

worsening vasogenic oedema (Figure 7). The patient

was followed up by the neurosurgery and oncology

teams and underwent radiotherapy of the whole brain

and the cervical spinal cord as palliative care. At 35

months after the initial presentation, the patient died due

to a complication of pneumonia.

Figure 5. T2-weighted imaging

at (a) 5 months posttreatment

(taken in June 2022) and (b) 16

months posttreatment (taken in

May 2023) shows enlargement of

the left cerebellar lesion (arrows).

T1-weighted post-contrast images

of the same lesion at (c) 5 months

posttreatment and (d) 16 months

posttreatment (arrows).

Figure 6. Selected positron emission

tomography–computed tomography

images using gallium-68-DOTATATE

tracer show multiple intra-axial

hypermetabolic nodules in the brain

and are consistent with known

neuroendocrine tumour metastases.

No obvious primary malignancy is

identified elsewhere.

Figure 7. T2-weighted axial image taken in March 2024 shows

further disease progression, with interval increase in the size

and number of metastatic lesions (arrows), as well as extensive

cerebral oedema.

DISCUSSION

Neurocysticercosis and neuroendocrine tumour of the

brain are two distinct entities that require very

different treatment approaches. The patient’s presenting

signs and symptoms (such as headache, dizziness and

seizure) are often non-specific. Serology testing for

Taenia solium, while specific, is often not sensitive. A

negative serology test does not exclude the diagnosis

of neurocysticercosis; hence, it was reasonable for our patient to undergo a trial of antiparasitic treatment based

on radiological appearance alone.

Imaging plays an important role in guiding the diagnosis

as well as treatment in such difficult cases. Nonetheless,

as with our case, imaging also has its limitations and can

be misguided by disease mimics.

On MRI, neurocysticercosis has varied radiological

appearances depending on its four main stages.[10] [11]

During the vesicular stage, cysts with cerebrospinal

fluid (CSF) intensity are often seen, sometimes with an

eccentric scolex that may show enhancement. Typically,

no surrounding vasogenic oedema is seen at this stage.

Intraventricular cysts may be difficult to visualise, and

heavily T2-weighted sequences such as FIESTA (fast

imaging employing steady-state acquisition) may help delineate the walls and scolex of neurocysticercosis. In

addition, the cystic content may show a slightly lower

signal compared with CSF, making them stand out.[12] For

our case, the FIESTA sequence was not performed due

to limited resources.

During the colloidal vesicular stage, cysts will often

contain increased proteinaceous content, leading to T1

and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintense

signal relative to CSF. Thickening and enhancement of

the cyst wall, as well as surrounding oedema, may be

seen. Some lesions may also show restricted diffusion,[11]

as in our case, which further complicates the clinical picture.

During the granular nodular stage, the cystic component

will resolve, becoming a small enhancing nodule.

Contrast enhancement and perilesional oedema will

gradually decrease and eventually resolve in the final

nodular calcified stage, where calcified nodules are seen. Neuroendocrine tumour of the brain, whether primary

or secondary, can also have variable appearances

mimicking other diseases. Among the reported primary

cases, MRI appearances ranged from a

solid enhancing mass to a cystic mass with a peripheral

enhancing component.[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9]

Spontaneous regression of up to one quarter of

neuroendocrine tumours has also been reported, albeit

most were extracranial in location, possibly due to host

immune response against neoantigens expressed by the

tumour.[13] This further increases diagnostic confusion, as

in our patient, and led us to interpret the regression of

lesions as a partial response to antiparasitic treatment.

Other imaging modalities such as PET scan may

offer more diagnostic clues, but 18F-FDG, which is

the most common tracer, may not show uptake in well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumours. On the

contrary, Ga-68-DOTATATE has a high sensitivity and

specificity in the detection of neuroendocrine tumours.[14]

Contrary to 18F-FDG which targets glucose metabolism,

Ga-68-DOTATATE targets somatostatin receptors that

are usually overexpressed by neuroendocrine tumours.

Nonetheless, this tracer is not yet widely available in our

region.

With hindsight, there are lessons to be learnt from

our patient and improvements to be made, especially

in her management. There was an 11-month period

(between 5 and 16 months posttreatment) with

no imaging follow-up or further workup. There were

already significantly enlarging lesions on the 5-month

posttreatment scan, and although present, regression of

the temporal lesions was subtle. More aggressive follow-up

imaging (e.g., within a few months) would have been

appropriate.

Furthermore, brain parenchymal haemorrhage, which

was already present on her initial MRI scan, is an

uncommon finding in neurocysticercosis. Alternative

differential diagnoses should have been considered,

especially in view of the suboptimal radiological

response to antiparasitic treatment. Given the vital

location of the enlarging lesions, further investigations

such as brain biopsy should also have been considered

and offered at an earlier stage.

Although treatment trials with antiparasitic drugs and

interval follow-up scans may provide a general idea of

the course of the disease, histological diagnosis including

excisional biopsy may be the only means by which to

confirm a diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

Neurocysticercosis in our region is uncommon, and

neuroendocrine tumour of the brain is even rarer. We

encountered an atypical presentation of a neuroendocrine

tumour of the brain mimicking neurocysticercosis. A

multidisciplinary approach involving the infectious diseases team, as well as neurosurgical and oncological

specialists, is necessary to reach definitive diagnosis.

REFERENCES

1. Caro-Osorio E, Perez-Ruano LA, Martinez HR, Rodriguez-Armendariz AG, Lopez-Sotomayor DM. Primary neuroendocrine

carcinoma of the cerebellopontine angle: a case report and literature

review. Cureus. 2022;14:e27564. Crossref

2. Porter DG, Chakrabarty A, McEvoy A, Bradford R. Intracranial

carcinoid without evidence of extracranial disease. Neuropathol

Appl Neurobiol. 2000;26:298-300. Crossref

3. Deshaies EM, Adamo MA, Qian J, DiRisio DA. A carcinoid tumor

mimicking an isolated intracranial meningioma. Case report. J

Neurosurg. 2004;101:858-60. Crossref

4. Ibrahim M, Yousef M, Bohnen N, Eisbruch A, Parmar H. Primary

carcinoid tumor of the skull base: case report and review of the

literature. J Neuroimaging. 2010;20:390-2. Crossref

5. Hakar M, Chandler JP, Bigio EH, Mao Q. Neuroendocrine

carcinoma of the pineal parenchyma. The first reported case. J Clin

Neurosci. 2017;35:68-70. Crossref

6. Liu H, Wang H, Qi X, Yu C. Primary intracranial neuroendocrine

tumor: two case reports. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:138. Crossref

7. Reed CT, Duma N, Halfdanarson T, Buckner J. Primary

neuroendocrine carcinoma of the brain. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:e230582. Crossref

8. Tamura R, Kuroshima Y, Nakamura Y. Primary neuroendocrine

tumor in brain. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2014;2014:295253. Crossref

9. Stepien N, Haberler C, Theurer S, Schmook M, Lütgendorf-Caucig

C, Müllauer L, et al. Unique finding of a primary central nervous

system neuroendocrine carcinoma in a 5-year-old child: a case

report. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:810645. Crossref

10. Teitelbaum GP, Otto RJ, Lin M, Watanabe AT, Stull MA, Manz HJ, et al. MR imaging of neurocysticercosis. AJR Am J

Roentgenol. 1989;153:857-66. Crossref

11. Santos GT, Leite CC, Machado LR, McKinney AM, Lucato LT.

Reduced diffusion in neurocysticercosis: circumstances of

appearance and possible natural history implications. AJNR Am J

Neuroradiol. 2013;34:310-6. Crossref

12. Neyaz Z, Patwari SS, Paliwal VK. Role of FIESTA and SWAN

sequences in diagnosis of intraventricular neurocysticercosis.

Neurol India. 2012;60:646-7. Crossref

13. Amoroso V, Agazzi GM, Roca E, Fazio N, Mosca A, Ravanelli M, et al. Regression of advanced neuroendocrine tumors among

patients receiving placebo. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2017;24:L13-6. Crossref

14. Yang J, Kan Y, Ge BH, Yuan L, Li C, Zhao W. Diagnostic role

of Gallium-68 DOTATOC and Gallium-68 DOTATATE PET in

patients with neuroendocrine tumors: a meta-analysis. Acta Radiol

2014;55:389-98. Crossref