Journal

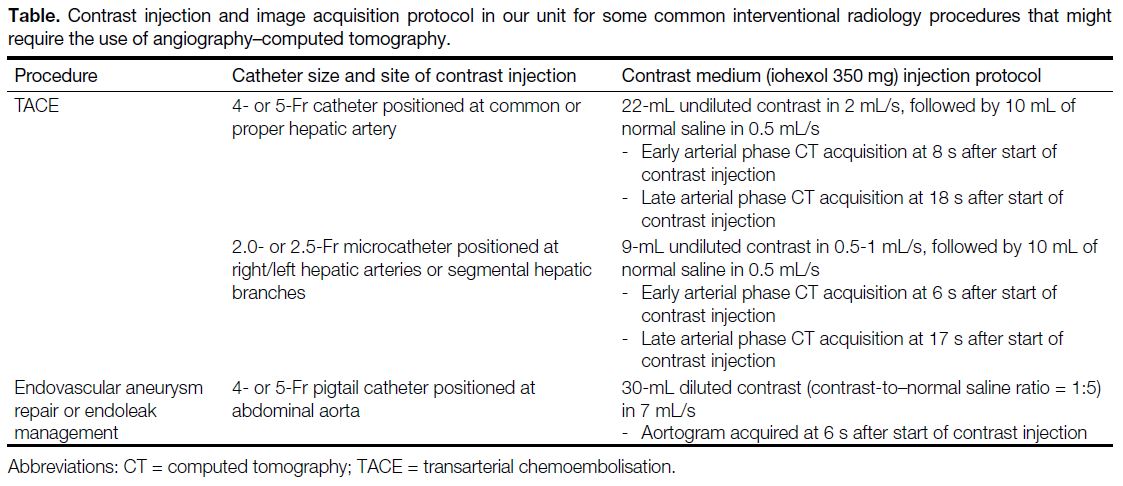

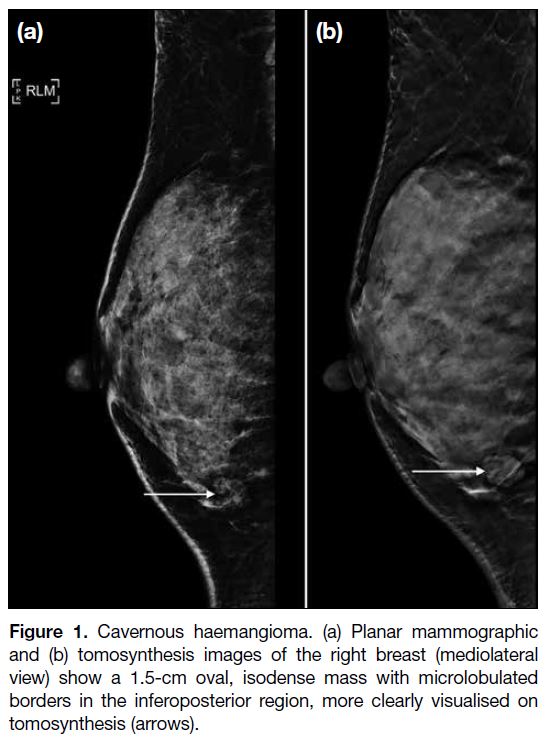

Vol. 28 No. 4, 2025

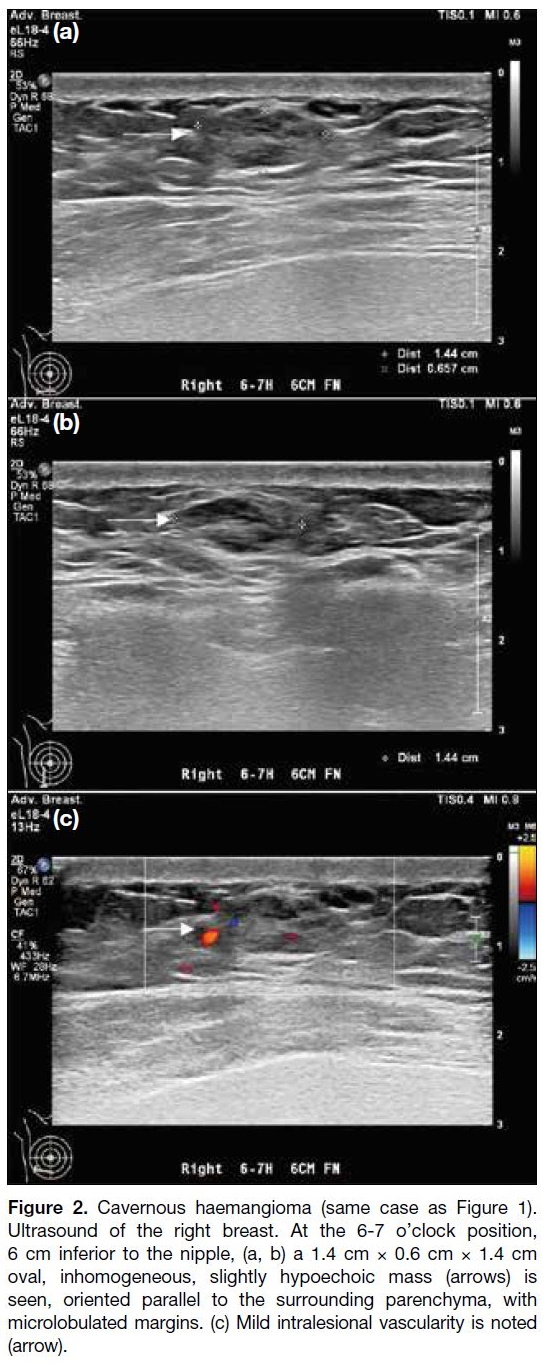

Table of Contents

EDITORIAL

More than the Sum of Its Parts: The Synergy of Hybrid Angiography–Computed Tomography Systems in Interventional Radiology

EDITORIAL

More than the Sum of Its Parts: The Synergy of Hybrid

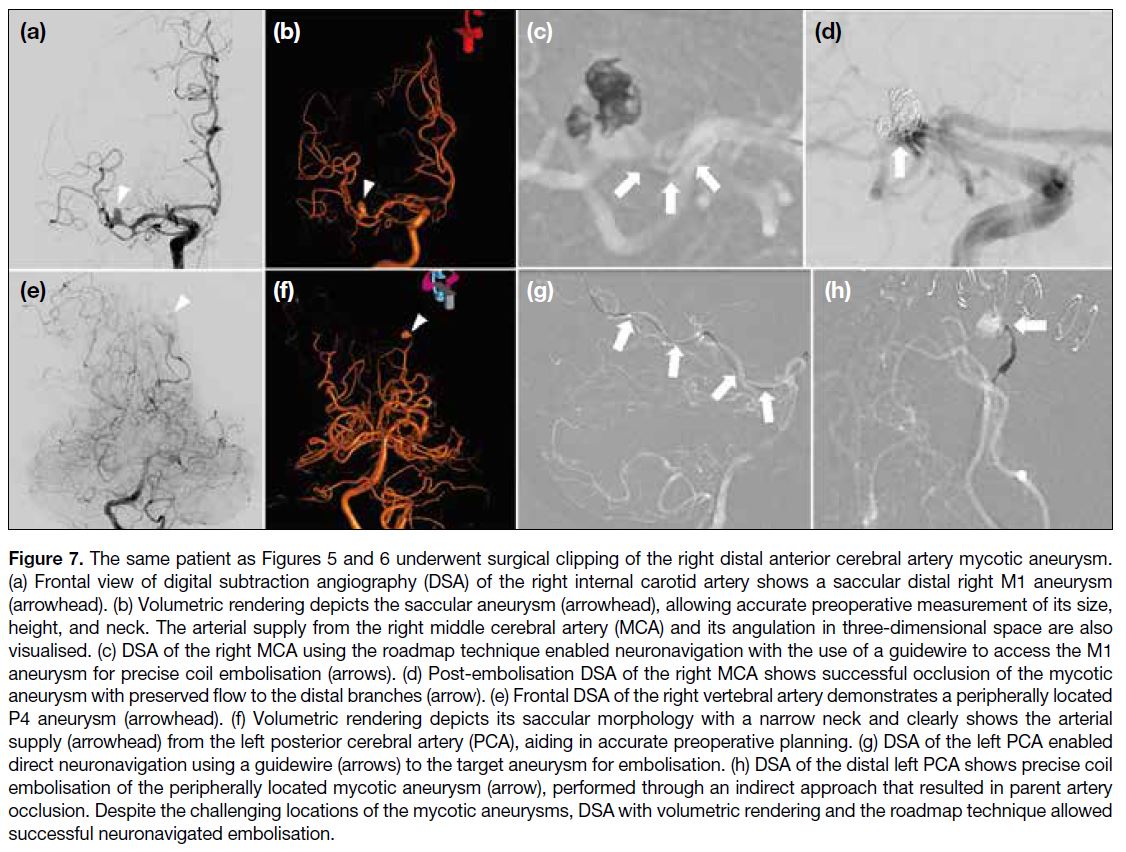

Angiography–Computed Tomography Systems in Interventional Radiology

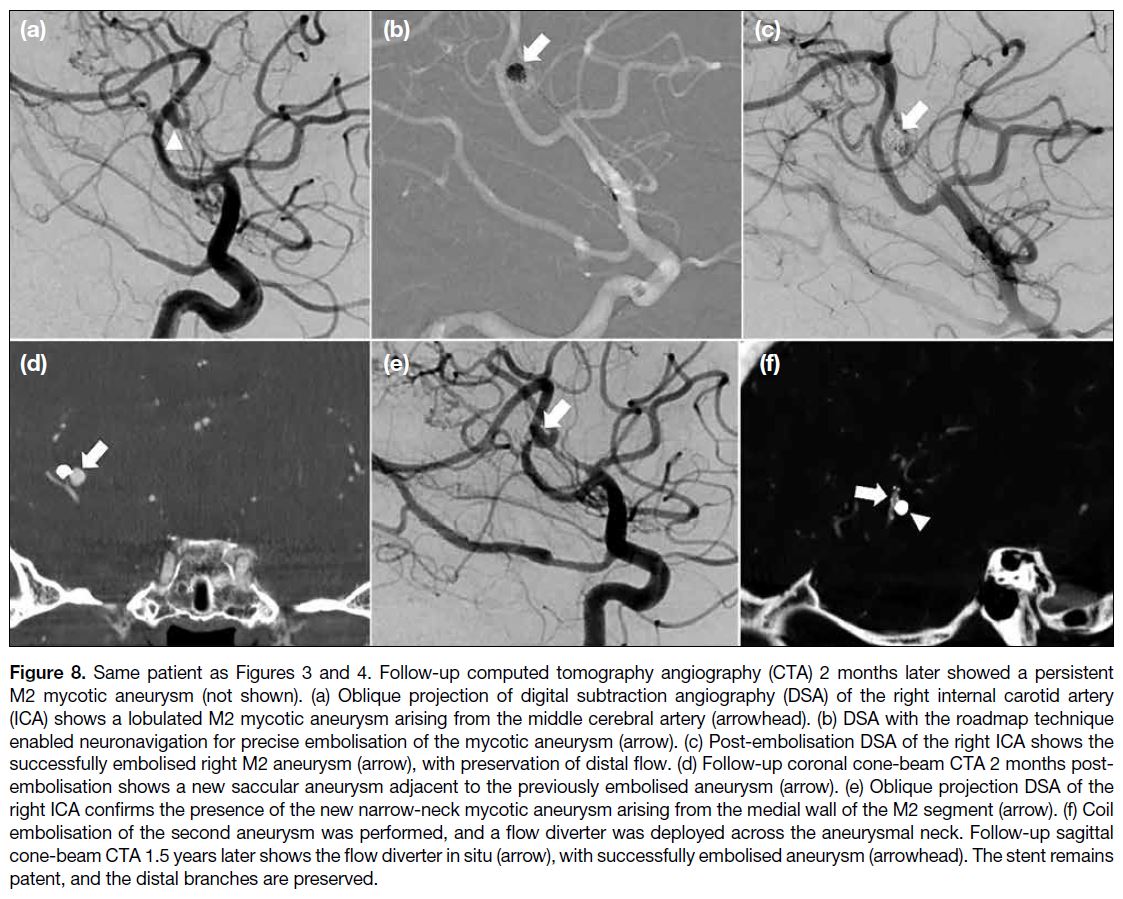

KKF Fung

Department of Radiology, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr KKF Fung, Department of Radiology, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: k.fung@ha.org.hk

Contributors: The author solely contributed to the editorial, approved the final version for publication, and takes responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: The author of this editorial is also a co-author of the article by Wong et al (Reference 4), published in the same issue. This

editorial represents the author’s objective interpretation of the topic and was not subject to internal peer review.

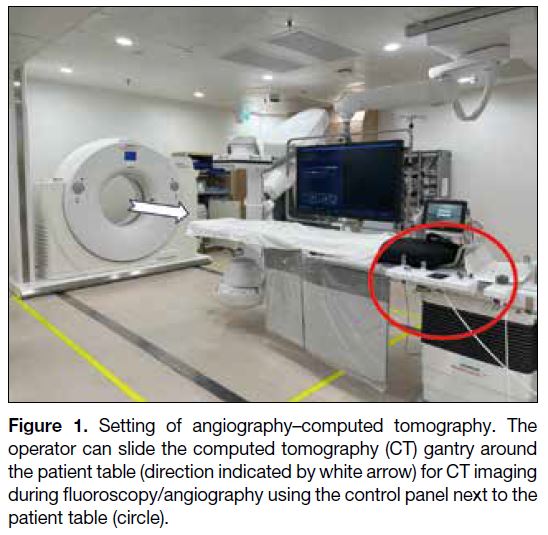

The introduction of cross-sectional imaging during

procedures has greatly improved treatment precision and

allowed real-time assessment of therapeutic outcomes,

particularly in the realm of interventional oncology. The

first hybrid angiography–computed tomography (angio-CT) system was developed in the early 1990s by Professor

Yasuaki Arai at Aichi Medical Centre in Japan.[1] In its

early stages, integration between the two modalities

was minimal, with each operating largely independently

and requiring the operator to manually combine the

imaging data.[2] The development of flat-panel detectors

in the late 1990s paved the way for the rapid adoption of

cone beam CT (CBCT). Compared to angio-CT, CBCT

has since become the more widely utilised modality,[3]

largely attributable to the higher cost and infrastructural

demands of angio-CT systems, particularly the need to

accommodate a sliding gantry. However, recent advances

in workflow efficiency, decreasing relative costs, and

the multipurpose capabilities of angio-CT systems have

led to renewed interest. Increasingly, institutions are

accepting the higher upfront investment, recognising the

potential long-term benefits in terms of improved patient

outcomes and enhanced procedural room utilisation.

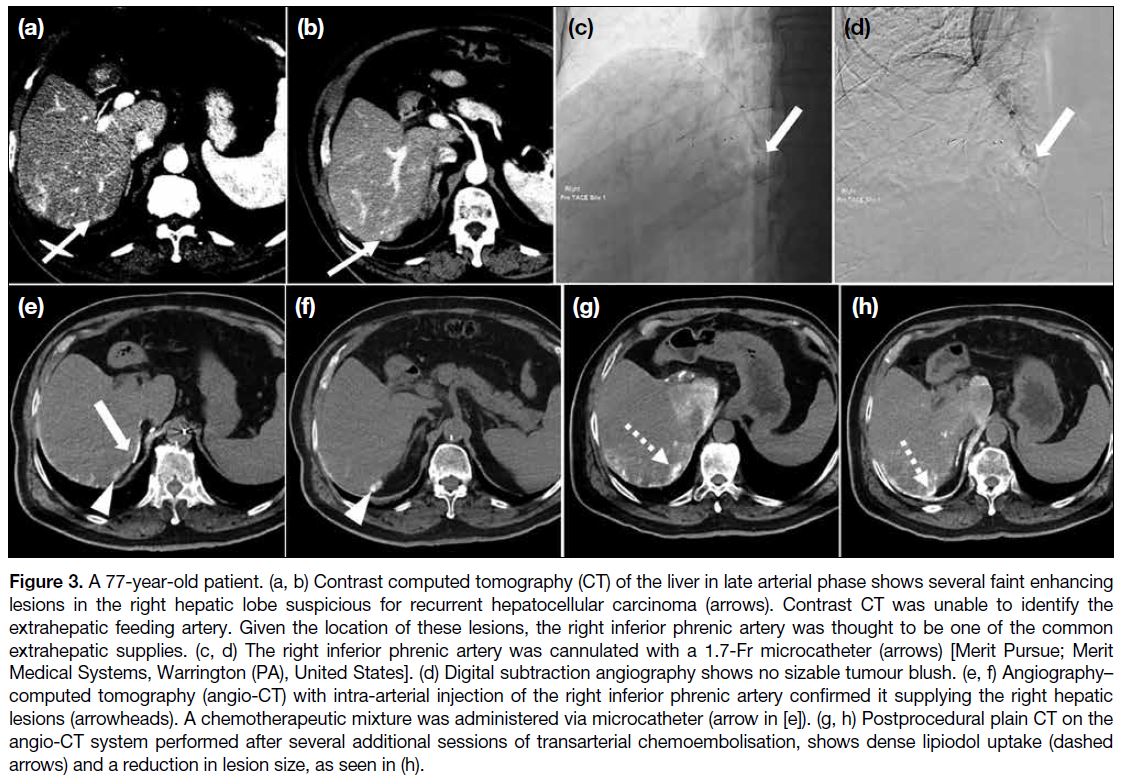

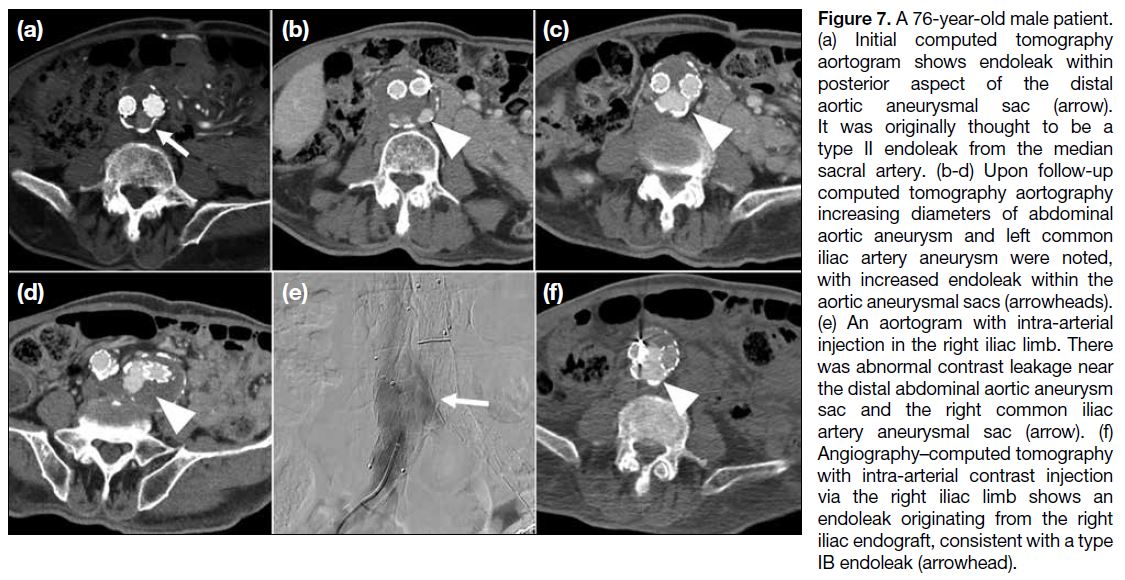

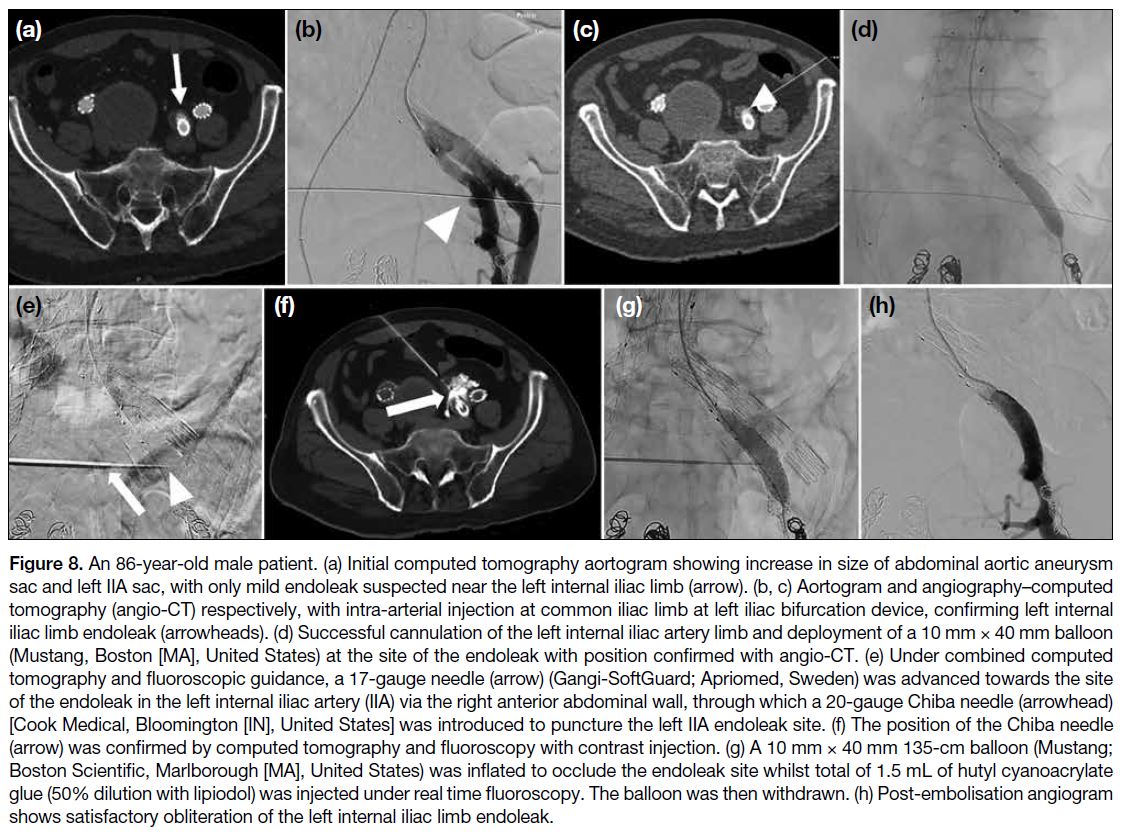

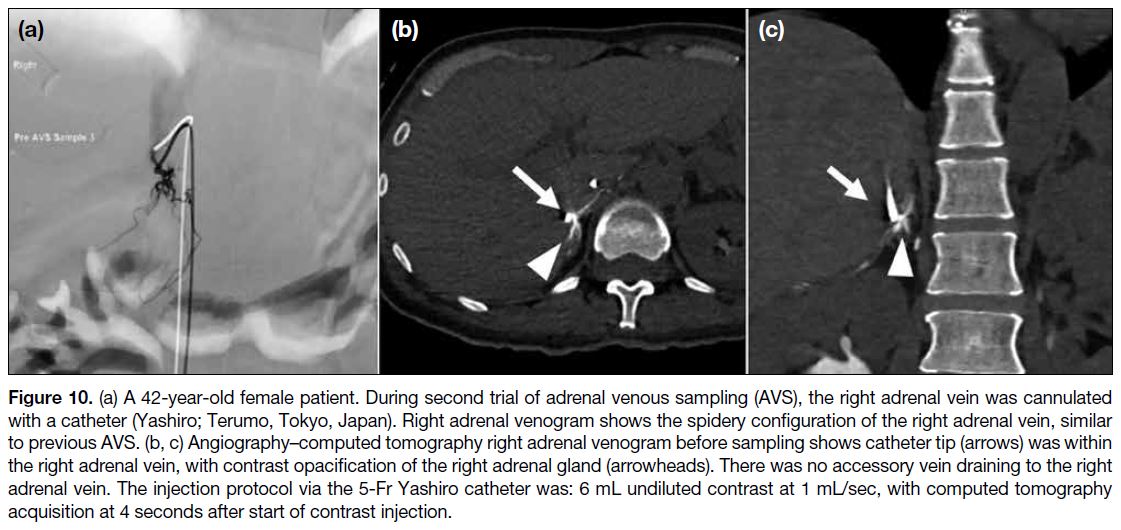

In this issue of the Hong Kong Journal of Radiology,

Wong et al[4] presented a case-based review that explores

the advantages of angio-CT technology through a series

of illustrative examples. While most of the interventional

radiology (IR) literature has focused primarily on

oncologic applications, this review highlights its broader utility in various vascular interventions, including

embolotherapy for acute haemorrhage, management

of pulmonary arteriovenous fistulae, and adrenal

venous sampling. Additional potential non-oncological applications—though not addressed in this review—

include complex drain placements, acute trauma

management, prostate artery embolisation, geniculate

artery embolisation, complex venous reconstruction, and

lymphatic interventions.[5] [6] These examples underscore

the versatility of angio-CT systems across a wide

spectrum of IR procedures.

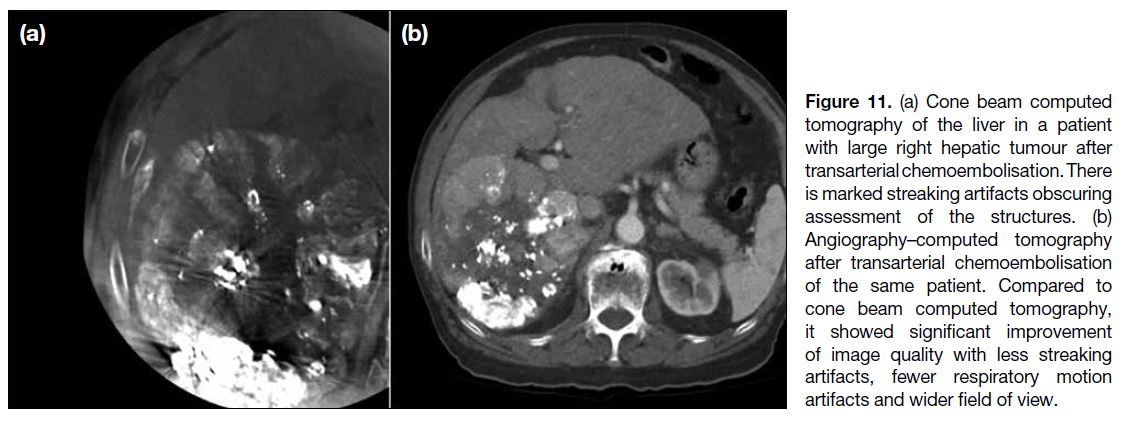

The most significant advantage of angio-CT lies in

its ability to integrate high-resolution CT imaging

with selective angiography and fluoroscopy, thereby

eliminating the need to transfer patients to a separate

CT scanner during critical procedural steps. Motion

and beam-hardening artefacts commonly encountered

with CBCT are minimised with angio-CT due to its

superior temporal resolution. The capacity to accurately

delineate perfused tissue volume is particularly

valuable in procedures where extra-target embolisation

may have serious consequences, such as geniculate

artery embolisation and prostate artery embolisation.

Additionally, the ability to provide three-dimensional

needle guidance is invaluable for complex interventions

such as sharp recanalisation in venous reconstructions

and antegrade percutaneous puncture of the cisterna

chyli. In the setting of acute polytrauma and stroke,

angio-CT enables both diagnostic CT and subsequent therapeutic embolisation to be performed within the

same gantry, thereby saving precious time and reducing

the risks associated with transferring critical, often

haemodynamically unstable, patients from one venue to

another.

Converting a conventional IR suite into a hybrid angio-CT

suite has been shown to enhance operational efficiency

across both IR and diagnostic radiology services. This

conversion allows CT scanners, which previously had

to be shared between diagnostic and interventional

services, to be dedicated solely to diagnostic imaging,

while enabling CT-guided procedures to be performed

directly within the hybrid IR suite. For instance, one

institution reported a 19.1% relative increase in the

utilisation of formerly shared CT scanners for diagnostic

imaging, along with a 287.1% relative increase in the use

of the hybrid IR suite, compared with the overall growth

rates of both diagnostic radiology and IR departments.[7] [8]

In addition, the potential use of the angio-CT scanner as

a diagnostic scanner affords scheduling flexibility for

both patients and physicians and contributes to workflow

efficiency and optimisation.

A major limitation of angio-CT systems is the

substantially higher cost of installation compared with

single-modality fluoroscopy suites. In addition, these

systems require a larger physical footprint, typically at

least 50 m2, to accommodate both CT and fluoroscopy

units. To date, robust quantitative evidence demonstrating

improved patient outcomes or cost-effectiveness is

lacking. Comparison of radiation dose between CBCT

and angio-CT is also challenging due to variability in

imaging protocols and technical parameters, which

introduces uncertainties in direct comparisons. Notably,

a CT acquisition during a procedure may reduce the

need for multiple digital subtraction angiography runs,

thereby lowering and more evenly distributing overall

radiation exposure to the patient. While one study found

no significant difference in effective dose per CT scan

between CBCT and angio-CT,[9] limited available data

suggest that angio-CT systems may reduce the overall

effective dose from both CT and angiographic imaging

compared with CBCT systems.[10]

Hybrid angio-CT systems offer institutions a valuable opportunity to expand treatment capabilities and

optimise workflow. The integration of diagnostic-quality

intraprocedural CT with conventional angiography

and fluoroscopy has substantially broadened the scope

of interventional procedures while improving room

utilisation. While the synergistic benefits of angio-CT

are clear, the decision to invest in such a system should

be informed by a comprehensive needs assessment

and institutional considerations, including case mix,

procedural complexity, patient volume, and the potential

to enhance workflow efficiency and translate into

improved patient outcomes.

REFERENCES

1. Tanaka T, Arai Y, Inaba Y, Inoue M, Nishiofuku H, Anai H, et al.

Current role of hybrid CT/angiography system compared with

C-arm cone beam CT for interventional oncology. Br J Radiol.

2014;87:20140126. Crossref

2. Taiji R, Lin EY, Lin YM, Yevich S, Avritscher R, Sheth RA, et al.

Combined angio-CT systems: a roadmap tool for precision

therapy in interventional oncology. Radiol Imaging Cancer.

2021;3:e210039. Crossref

3. Floridi C, Radaelli A, Abi-Jaoudeh N, Grass M, De Lin M,

Chiaradia M, et al. C-arm cone-beam computed tomography in

interventional oncology: technical aspects and clinical applications.

Radiol Med. 2014;119:521-32. Crossref

4. Wong CL, Fung KK, Lo HY, Yeung LH, Ng JC, Lee KH, et al.

Exploring the power of hybrid intervention: utility of angiography–

computed tomography system in interventional radiology. Hong

Kong J Radiol. 2025;28:e257-67. Crossref

5. Wong D, Fung KF, Chen HS, Lun KS, Kan YL. Intranodal conebeam

computed tomographic lymphangiography with water-soluble

iodinated contrast agent for evaluating chylothorax in infants—preliminary experience at a single institution. Pediatr Radiol.

2023;53:179-83. Crossref

6. Wong D, Fung KF, Chen HS, Lun KS, Kan YL. Re: Pediatric

intranodal CT lymphangiography with water-soluble contrast

media. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2023;34:1451. Crossref

7. Feinberg N, Funaki B, Hieromnimon M, Guajardo S, Navuluri R,

Zangan S, et al. Improved utilization following conversion of a

fluoroscopy suite to hybrid CT/angiography system. J Vasc Interv

Radiol. 2020;31:1857-63. Crossref

8. Kwak DH, Ahmed O, Habib H, Nijhawan K, Kumari D, Patel M.

Hybrid CT-angiography (angio-CT) for combined CT and

fluoroscopic procedures in interventional radiology enhances

utilization. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2022;47:2704-11. Crossref

9. Marshall EL, Guajardo S, Sellers E, Gayed M, Lu ZF, Owen J, et al.

Radiation dose during transarterial radioembolization: a dosimetric

comparison of cone-beam CT and angio-CT technologies. J Vasc

Interv Radiol. 2021;32:429-38. Crossref

10. Piron L, Le Roy J, Cassinotto C, Delicque J, Belgour A, Allimant C,

et al. Radiation exposure during transarterial chemoembolization:

angio-CT versus cone-beam CT. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol.

2019;42:1609-18. Crossref

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

Efficacy of Prophylactic Embolisation of Renal Angiomyolipomas Using Semi-automatic Segmentation for Volume Measurement

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Hong Kong J Radiol 2025 Dec;28(4):e234-42 | Epub 17 November 2025

Efficacy of Prophylactic Embolisation of Renal Angiomyolipomas Using Semi-automatic Segmentation for Volume Measurement

PL Lam1, JC Ng1, KH Lee1, KKF Fung2, DHY Cho1

1 Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Radiology, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr PL Lam, Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR,

China. Email: lpl404@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 28 August 2024; Accepted: 29 October 2024.

Contributors: All authors designed the study. PLL acquired the data. All authors analysed the data. PLL drafted the manuscript. All authors

critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the

final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: As an editor of the journal, KKFF was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This research was approved by the Central Institutional Review Board of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: CIRB-2024-022-4). The requirement for informed patient consent was waived by the Board due to the retrospective nature of the research.

Abstract

Introduction

We aimed to assess the efficacy of prophylactic embolisation of renal angiomyolipomas (AMLs) by

determining post-embolisation rupture risk, as well as changes in total volume and in angiomyogenic and fatty

components using semi-automatic segmentation.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of 22 adult patients with prophylactic embolisation of AML performed

between January 2009 and January 2024. Patients were followed up for any post-embolisation rupture. Pre- and

post-embolisation computed tomography (CT) data were assessed using the open-source software 3D Slicer for

semi-automatic segmentation. Volumetric changes of AMLs were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test

for paired data and Mann-Whitney U test for unpaired data. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to

identify any associations between variables.

Results

There were 25 prophylactic embolisations performed on the 22 adult patients with AML (18 females

[81.8%]), with a median age of 60.0 years (interquartile range [IQR], 15.0). No procedure-related complications

were encountered. The median follow-up was 49.0 months (IQR, 56.0) with no post-embolisation rupture. Pre- and

post-treatment median tumour volumes were 67.5 cm3 (IQR, 116.1) and 35.7 cm3 (IQR, 82.1), respectively. There

was a significant reduction in total tumour volume (41.4%), including angiomyogenic (73.6%) and fatty components

(14.0%) [all p < 0.001]. Factors associated with greater tumour volume reduction included a higher proportion of

angiomyogenic and a lower proportion of fatty components (both p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Prophylactic embolisation of AML effectively reduced tumour volume, with more significant changes

in its angiomyogenic than fatty components. No post-embolisation rupture was documented with a median follow-up of over 4 years.

Key Words: Angiomyolipoma; Embolization, therapeutic; Hemorrhage; Kidney neoplasms; Tumor burden

中文摘要

半自動分割體積測量法評估預防性栓塞治療腎血管平滑肌脂肪瘤的療效

林栢麟、吳昆倫、李家灝、馮建勳、曹慶恩

引言

本研究旨在透過半自動分割技術評估腎血管平滑肌脂肪瘤(AML)預防性栓塞的療效,具體方法包括確定栓塞術後破裂風險以及腫瘤總體積、血管肌源性成分和脂肪成分的變化。

方法

本研究為回顧性研究,納入2009年1月至2024年1月期間接受AML預防性栓塞的22位成年患者。所有患者均接受隨訪,觀察栓塞術後是否發生破裂。我們採用開源軟件3D Slicer對栓塞術前及術後的電腦斷層掃描圖像進行半自動分割,並採用Wilcoxon 符號排序檢定(配對資料)和Mann-Whitney U 檢定(非配對資料)比較AML的體積變化,以及採用Spearman秩相關系數分析各變數間的相關性。

結果

22位成年AML患者(18位女性[81.8%])接受了25次預防性栓塞治療,中位年齡為60.0歲(四分位數間距[IQR]為15.0)。沒有發生手術相關併發症。中位隨訪時間為49.0個月(IQR為56.0),沒有發生栓塞後破裂。治療前後腫瘤體積中位數分別為67.5 cm3(IQR為116.1)及35.7 cm3(IQR為82.1)。腫瘤總體積顯著縮小(41.4%),其中血管肌源性成分縮小73.6%,脂肪成分縮小14.0% [所有p < 0.001]。腫瘤體積顯著縮小的相關因素包括血管肌源性成分比例較高和脂肪成分比例較低(兩者 p < 0.001)。

結論

預防性栓塞治療AML可有效縮小腫瘤體積,且血管肌源性成分的變化比脂肪組成的變化更為顯著。中位隨訪時間超過4年,未記錄到栓塞後破裂病例。

INTRODUCTION

Renal angiomyolipoma (AML) is the most common

benign solid renal tumour.[1] The majority (approximately

80%) occur sporadically, while the rest (approximately

20%) are associated with phakomatoses, most

commonly tuberous sclerosis.[2] AML belongs to the

family of tumours with perivascular epithelioid cellular

differentiation.[3] It typically contains both angiomyogenic

and fatty components, with the latter readily identifiable

in computed tomography (CT) due to its hypoattenuating

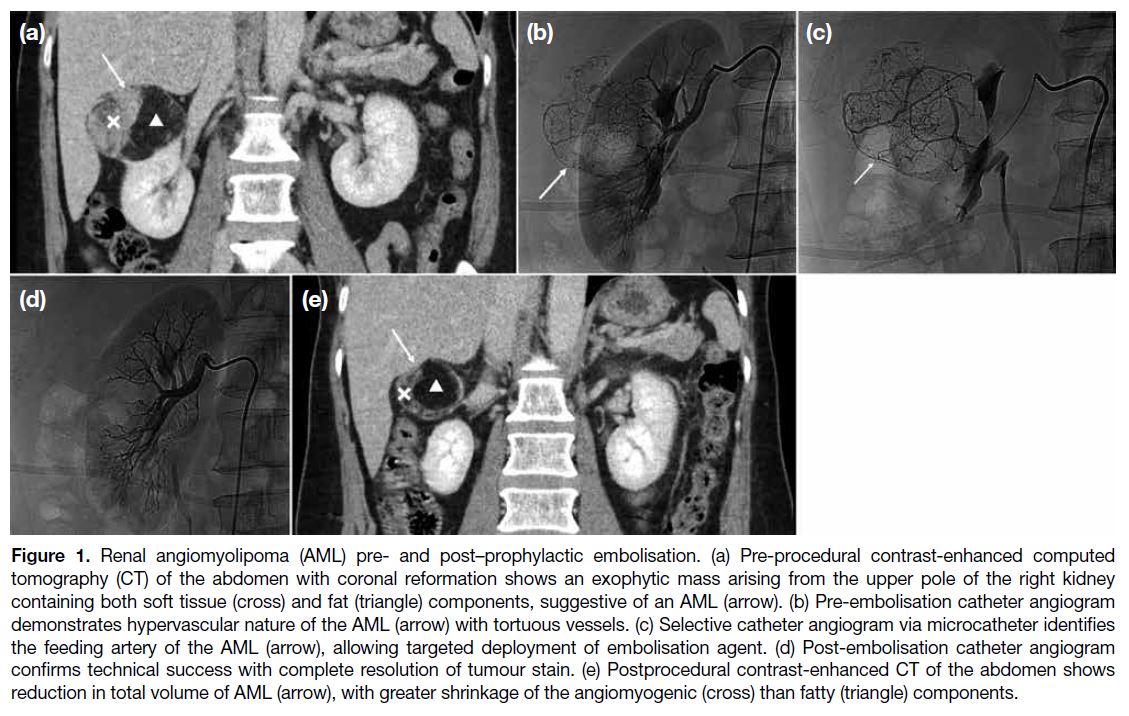

nature (< -10 Hounsfield unit [HU]) [Figure 1].[4] [5]

Figure 1. Renal angiomyolipoma (AML) pre- and post–prophylactic embolisation. (a) Preprocedural contrast-enhanced computed

tomography (CT) of the abdomen with coronal reformation shows an exophytic mass arising from the upper pole of the right kidney

containing both soft tissue (cross) and fat (triangle) components, suggestive of an AML (arrow). (b) Pre-embolisation catheter angiogram

demonstrates hypervascular nature of the AML (arrow) with tortuous vessels. (c) Selective catheter angiogram via microcatheter identifies

the feeding artery of the AML (arrow), allowing targeted deployment of embolisation agent. (d) Post-embolisation catheter angiogram

confirms technical success with complete resolution of tumour stain. (e) Postprocedural contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen shows

reduction in total volume of AML (arrow), with greater shrinkage of the angiomyogenic (cross) than fatty (triangle) components.

It is well recognised that AML carries a risk of rupture

with bleeding, especially for larger tumours, which can

lead to fatal consequences.[6] [7] Treatment options include

transcatheter arterial embolisation and radiofrequency

ablation, as well as partial or radical nephrectomy.[8]

Selective arterial embolisation can be performed in an

emergency setting for AML with active bleeding. It can

also be a prophylactic treatment to reduce tumour size

and its risk of haemorrhage (Figure 1).[9] [10] It has been

suggested that for AML of 4 cm or above in diameter, or

those with microaneurysms 0.5 cm or above in the feeding

artery, prophylactic selective arterial embolisation is indicated.[11] Different embolisation agents have been

reported in the literature, including microparticles, such

as microspheres, and liquid agents, such as ethanol. Past

studies have shown that prophylactic embolisation could

reduce the size of AML, thus reducing its haemorrhagic

risk.[9] [10] [12] In addition, the risk of haemorrhage is mainly

attributed to the angiomyogenic component of AML.[13] [14] [15]

Yet, there are limited studies accurately assessing how

tumour composition changes after treatment.

For AML, tumour size has been shown to be associated

with risk of spontaneous rupture, with larger ones

more likely to bleed.[6] [7] [11] This study therefore aimed

to assess the efficacy of prophylactic selective arterial

embolisation in determining the rupture risk post-embolisation

and reducing the volume of AML using

semi-automatic segmentation as a measurement tool.

Changes in its angiomyogenic and fatty components

were also evaluated.

METHODS

Patient Selection

This was a single-centre, single-arm retrospective

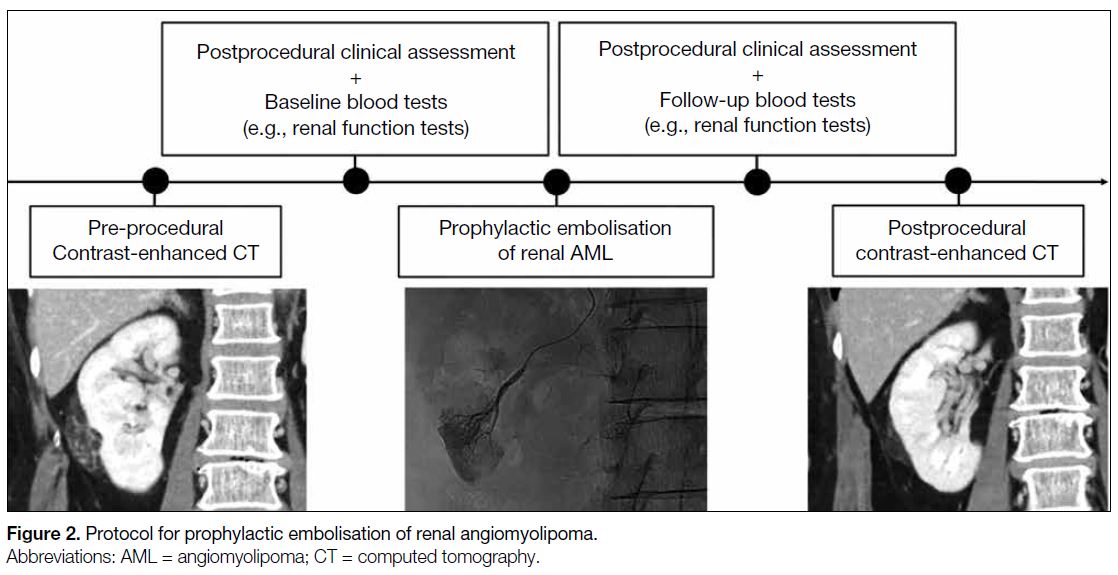

study. Consecutive adult patients (≥18 years old) who underwent prophylactic embolisation of AML (Figure 2) in a public acute general hospital between January

2009 and January 2024 were included. Exclusion criteria

included paediatric patients (<18 years old), patients

who underwent emergency embolisation of ruptured

AML, and patients without pre- or postprocedural CT.

Figure 2. Protocol for prophylactic embolisation of renal angiomyolipoma.

Data Collection

Clinical data of the included patients were retrieved from

the radiology information system of the hospital network.

They included demographics and medical history, such

as tuberous sclerosis status. Presenting symptoms and

postprocedural complaints were recorded. Pre- and post-intervention blood tests, such as haemoglobin level and

renal function tests, were documented.

Details of prophylactic embolisation of AML were

logged. They encompassed the type and amount of

embolisation agents deployed, as well as catheters

and guidewires used, which were chosen based on the

operators’ preference. Data on technical success, defined

as complete angiographic resolution of tumour stain

and microaneurysms, as well as contrast stasis of the

feeding artery, were documented. Intraoperative and

immediate postprocedural complications were recorded.

Subsequent clinical follow-up was reviewed for post-embolisation

tumour rupture.

Radiological Assessment

Pre- and post-embolisation plain and contrast-enhanced

CTs of the abdomen in DICOM (Digital Imaging and

Communications in Medicine) format were obtained

from the picture archiving and communication system

of the hospital network. The time interval between the

day of CT examination and interventional procedure

was logged. DICOM images were assessed using 3D

Slicer (macOS version 5.6.2; The Slicer Community),

an open-source image computing platform.[16] Semi-automatic

segmentation of AMLs was performed in

the following sequence (Figure 3): (1) reformation of

contrast-enhanced CT images in axial, coronal and

sagittal planes; (2) manual contouring of tumour and

non-tumour regions on limited CT slices (<5); (3)

automatic segmentation of tumour and non-tumour

regions using the ‘grow from seeds’ algorithm; (4)

manual refinement of segmented regions using ‘paint’

and ‘erase’ algorithms; (5) automatic differentiation

between angiomyogenic and fatty components of AML

using a ‘threshold’ algorithm, with the threshold set

at ≥ -10 HU for the angiomyogenic component and

< -10 HU for the fatty component; (6) automatic volume

rendering of tumour and non-tumour regions; and (7)

automatic volumetric computation of the entire AML,

as well as its angiomyogenic and fatty components. In

addition, laterality and polarity of AML, as well as the

presence or absence of aneurysms, were documented.

In postprocedural CT, any complications, including

renal parenchymal infarction, haematoma, abscess,

pyelonephritis, or hydronephrosis, were recorded.

Figure 3. Semi-automatic segmentation of renal

angiomyolipoma (AML) using 3D Slicer. (a) Digital Imaging

and Communications in Medicine images of contrastenhanced

computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen

are reformatted in the axial (upper left), coronal (lower

left), and sagittal planes (lower right). An AML (arrows)

arises from the upper pole of the left kidney. (b) Contrast-enhanced

CT of the abdomen reformatted in sagittal

planes. Contours of AML (arrows) and other non-tumour

regions are drawn manually on several (<5) CT slices. (c)

Automatic segmentation of AML (arrows) is performed

in the axial (upper left), coronal (lower left), and sagittal

planes (lower right) using the ‘grow from seeds’ algorithm.

Further refinement of the segmented regions is possible

using the ‘paint’ and ‘erase’ algorithms. Automatic three-dimensional

rendering of (d) non-tumour regions and (e)

the AML are shown. Further volumetric analysis, such as

determining the angiomyogenic and fatty components of

the AML using -10 Hounsfield unit as the threshold, can

be performed.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (macOS

version 29.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States).

The distribution of all numerical data was first tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The Wilcoxon

signed-rank test was used to compare paired data,

such as pre- and postprocedural volumetric changes

in each AML. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for

comparison between unpaired data. Spearman’s rank

correlation coefficient was used to identify association

between variables. A p value of < 0.05 was considered

statistically significant.

This manuscript was prepared in accordance with the

STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational

Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics and Clinical

Information

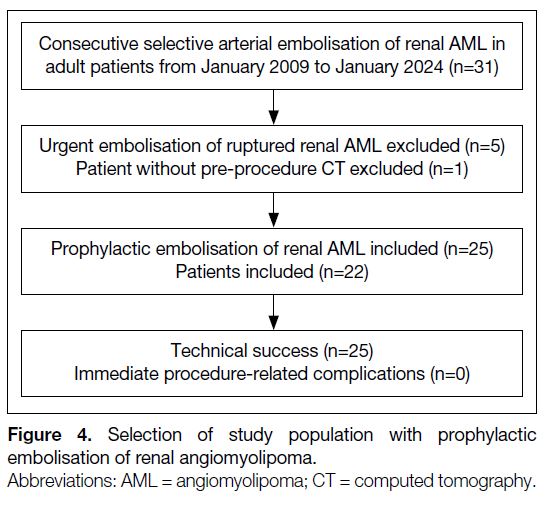

There were 31 prophylactic embolisations of AMLs

in adult patients performed from January 2009 to

January 2024. Five patients underwent emergent

embolisation of ruptured AMLs. One patient did not

have preoperative CT available for assessment. These

six patients were therefore excluded. A total of 25

prophylactic embolisations of AML in 22 patients were

finally included in the study, of which three patients had

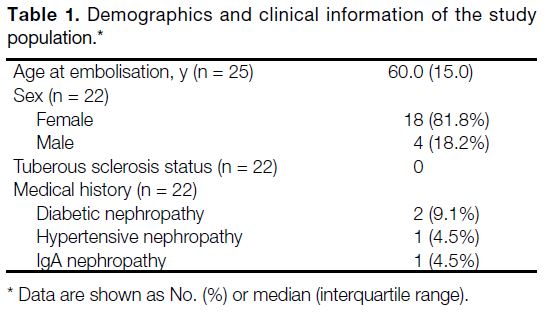

repeated embolisation (n = 3, 13.6%) [Figure 4]. The median age of the patients on the day of embolisation

was 60.0 years (interquartile range, 15.0). Most patients

were female (n = 18, 81.8%). There was no patient with

tuberous sclerosis. Four patients (18.2%) had known

chronic kidney disease due to diabetic nephropathy

(n = 2, 9.1%), hypertensive nephropathy (n = 1, 4.5%)

and IgA nephropathy (n = 1, 4.5%) [Table 1].

Figure 4. Selection of study population with prophylactic embolisation of renal angiomyolipoma.

Table 1. Demographics and clinical information of the study population.

Prophylactic Embolisation of Renal

Angiomyolipoma

All prophylactic embolisations of AMLs were performed

due to large tumour size (≥4 cm in diameter). In one

case (4.0%), there was a 0.5-cm aneurysm identified

in preprocedural assessment, which was successfully

embolised. Microspheres (Embosphere Microsphere;

Merit Medical Systems, South Jordan [UT], United

States) were employed in two-thirds of all interventions

(n = 17, 68.0%). The sizes of the microparticles ranged

between 100-300 μm (n = 2, 11.8%), 300-500 μm

(n = 6, 35.3%) and 500-700 μm (n = 9, 52.9%). Ethanol

was used in the remaining one-third of the cases (n = 8,

32.0%). Ethanol was radio-opacified with ethiodised

oil in a ratio of 7:3 for embolisation of the other cases.

Selective arterial embolisation with microcatheters

and microguidewires was performed in every case.

All prophylactic embolisation achieved technical success. There were no intra-procedural or immediate

postprocedural complications encountered. The median

time intervals between pre- and postprocedural CT with

prophylactic embolisation were 90.0 days and 107.0 days,

respectively. Postprocedural CT showed a small (2.0 cm

in diameter) subsegmental renal infarction in one case

(4.0%). No other complications were seen. There were

no significant changes in haemoglobin level or renal

function tests before and after prophylactic embolisation.

Median clinical follow-up duration was over 4 years

(49.0 months), with a minimum of 6 months. There were

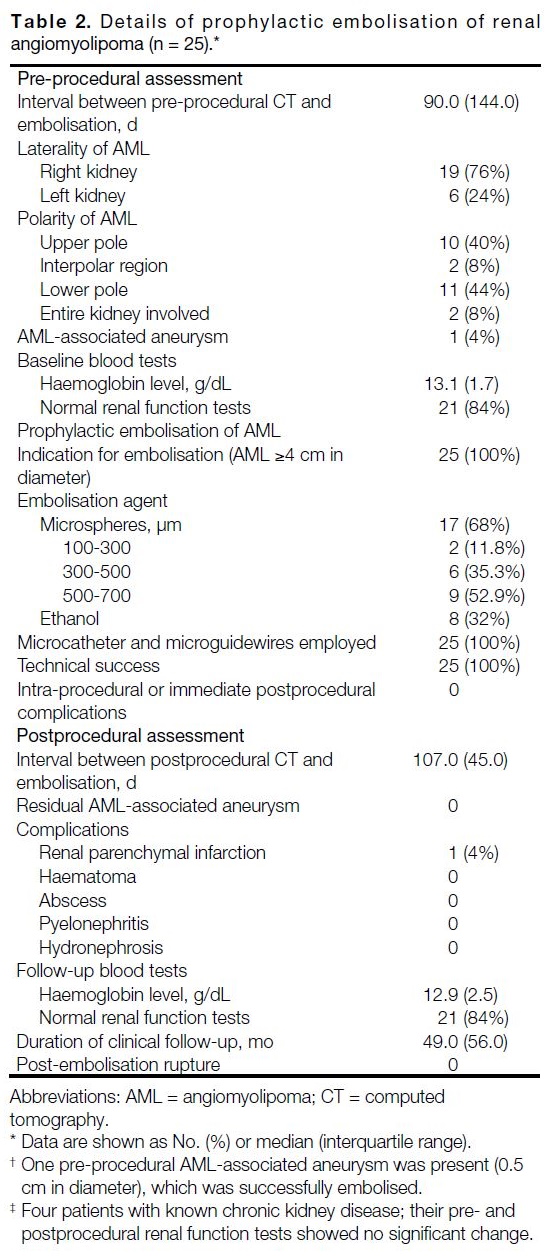

no post-embolisation rupture of AML (Table 2).

Table 2. Details of prophylactic embolisation of renal angiomyolipoma (n = 25).

Volumetric Analysis of Renal Angiomyolipoma

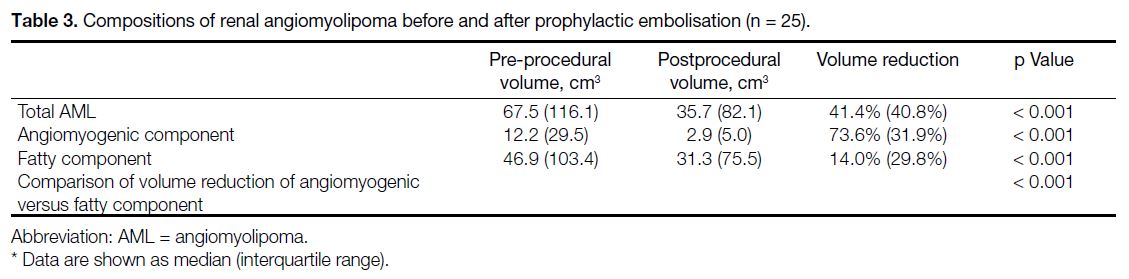

The median total volume of AMLs in pre- and

postprocedural CTs were 67.5 cm3 and 35.7 cm3,

respectively, showing significant interval shrinkage, with 41.4% total tumour volume reduction. Both

angiomyogenic and fatty components showed

significant interval reduction in size, attaining 73.6% and

14.0% volume loss, respectively. The angiomyogenic

component of the AMLs showed significantly greater

reduction in size compared to the fatty component

(Table 3).

Table 3. Compositions of renal angiomyolipoma before and after prophylactic embolisation (n = 25).

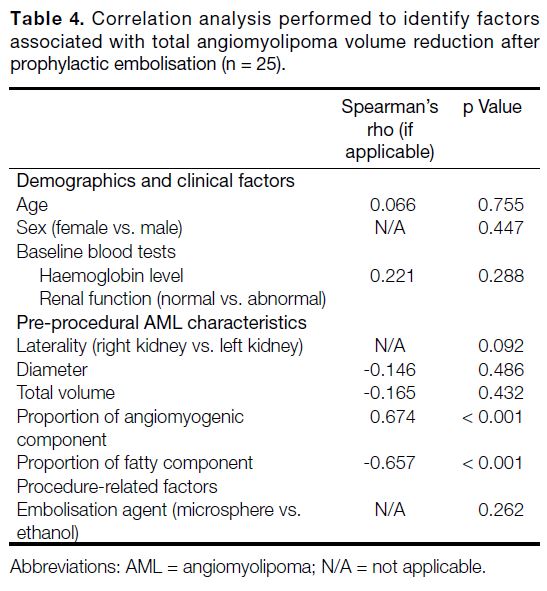

Correlation analysis revealed AMLs with a greater

proportion of angiomyogenic component and smaller

proportion of fatty component in preprocedural CT

were associated with greater tumour volume reduction

after prophylactic embolisation. No other clinical or

procedural factors associated with total tumour shrinkage

were identified (Table 4).

Table 4. Correlation analysis performed to identify factors associated with total angiomyolipoma volume reduction after prophylactic embolisation (n = 25).

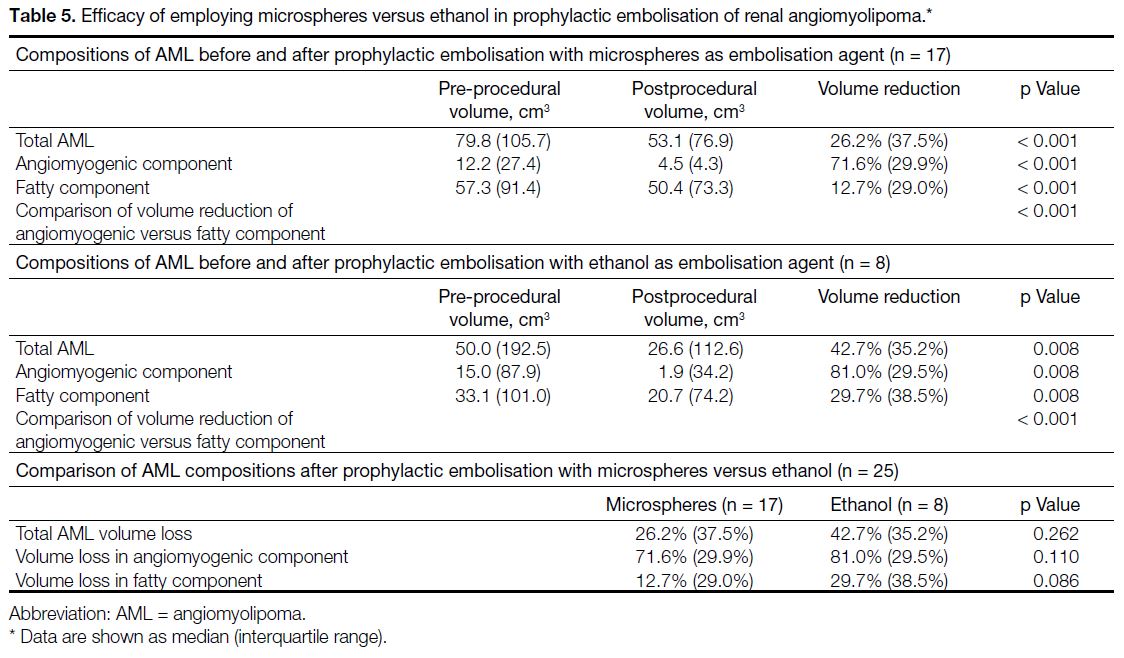

Prophylactic embolisation of AML with either

microspheres or ethanol achieved significant reduction

in total tumour size, with 26.2% (p < 0.001) and 42.7%

(p = 0.008) volume loss, respectively. Using either

embolisation agent, there were significant reduction

in volume of both angiomyogenic (microspheres:

71.6%, p < 0.001; ethanol: 81.0%, p = 0.008) and fatty

components (microspheres: 12.7%, p < 0.001; ethanol:

29.7%, p = 0.008), with the angiomyogenic component showing significantly greater volume loss than the fatty

component using either embolisation agent (both p < 0.001). Comparing microspheres and ethanol, there were

no statistically significant differences in their efficacy of

reduction of the total tumour volume, angiomyogenic or

fatty components of AML (Table 5).

Table 5. Efficacy of employing microspheres versus ethanol in prophylactic embolisation of renal angiomyolipoma.

DISCUSSION

Transcatheter embolisation of AML is recognised as

a safe intervention.[9] [10] Compared to more invasive

treatment options such as partial or radical nephrectomy,

transcatheter selective arterial embolisation typically

only requires local anaesthesia, has lower risks of

bleeding and infection, and allows shorter admission

times. Some authors therefore suggest transcatheter

embolisation as the first-line treatment option.[8] In our

study, no intra-procedural or immediate complications

were encountered. However, in one patient, a small

subsegmental renal infarction was seen in postprocedural

CT. This highlights the importance of follow-up imaging,

which encompasses assessment of treatment efficacy, as

well as identification of complications.

There was significant change in tumour volume after

prophylactic embolisation of AML, achieving over 40%

reduction in median total volume amongst our study

population. With decreased tumour volume, the risk of

spontaneous haemorrhage would be lowered.[6] [11] It was

reassuring that none of the included patients encountered

post-embolisation tumour rupture in clinical follow-up

with a median duration of over 4 years. These findings

demonstrate that prophylactic embolisation of AML is

a safe and effective means to reduce haemorrhagic risk,

concurrent with previous studies.[9] [10]

Various materials for prophylactic embolisation of

the kidney have been suggested in the literature,

with microspheres and ethanol being two of the

most commonly adopted agents. In this study, both microspheres and ethanol effectively reduced the size

of AMLs by over 25%, without a statistically significant

difference between the two agents. To the best of our

knowledge, there is no large-scale study establishing

whether microspheres or ethanol is the superior

prophylactic embolisation agent for AML.[9] [10] [12] In our centre, this choice depended on the operators’ preference.

It has been proposed that the effectiveness of

prophylactic embolisation in achieving volume reduction

depends on the composition of the AML, which has

variable angiomyogenic and fatty components. The

angiomyogenic component usually demonstrates

greater response to embolisation due to its vascular

nature, whereas the fatty component is hypovascular

and more treatment-resistant.[9] [17] A study by Han et al[17]

showed near-complete resolution of the angiomyogenic

component after prophylactic embolisation, but the

fatty component only partially shrank. In their study,

the proportion of angiomyogenic and fatty components

were evaluated on a transverse image at the middle

of the tumour. However, this might not reflect the

actual composition of the entire AML. In our study,

semi-automatic segmentation was performed, and the

angiomyogenic and fatty components were differentiated

using -10 HU as the threshold. This allowed a more accurate volumetric assessment of AML. Similar to

prior studies, there was significantly greater reduction in

the angiomyogenic component than the fatty component

after embolisation.

AMLs with a greater proportion of angiomyogenic

component and smaller proportion of fatty component

are associated with greater total volume reduction

after embolisation. For AML with high fatty content,

patients and clinicians may be concerned that about the

smaller postprocedural volume reduction. However,

the angiomyogenic component of AML, which is the

main culprit in haemorrhage, has shown good response

to embolisation.[9] [17] In our study, the angiomyogenic

component achieved over 70% volume reduction, which

could be reassuring to both patients and clinicians.

Limitations

First, none of the patients in our study had tuberous

sclerosis. Treatment efficacy for sporadic and tuberous

sclerosis–associated AML may differ and have not

been explored. Second, there was a lack of a control

group to compare rupture risk in patients who received

prophylactic embolisation versus those who did not. A

double-arm study could better assess treatment effect.

Third, the sample size was limited. This may be partly attributed to the relatively low prevalence of AML, which

is below 0.5% in the population.[18] A multi-centre study

with larger sample sizes is a potential future direction.

CONCLUSION

Prophylactic embolisation of AML effectively reduced

tumour volume, with more significant changes in the

angiomyogenic component compared to the fatty

component. No rupture or haemorrhage was documented

post-embolisation with a median follow-up of over 4

years.

REFERENCES

1. Prasad SR, Surabhi VR, Menias CO, Raut AA, Chintapalli KN.

Benign renal neoplasms in adults: cross-sectional imaging findings.

AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:158-64. Crossref

2. Steiner MS, Goldman SM, Fishman EK, Marshall FF. The natural history of renal angiomyolipoma. J Urol. 1993;150:1782-6. Crossref

3. Chan TY. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology & genetics of tumours of the urinary system and male

genital organs. Urology. 2005;65:214-5. Crossref

4. Halpenny D, Snow A, McNeill G, Torreggiani WC. The radiological diagnosis and treatment of renal angiomyolipoma—current status.

Clin Radiol. 2010;65:99-108. Crossref

5. Park BK. Renal angiomyolipoma: radiologic classification and

imaging features according to the amount of fat. AJR Am J

Roentgenol. 2017;209:826-35. Crossref

6. Ruud Bosch JL, Vekeman F, Duh MS, Neary M, Magestro M, Fortier J, et al. Factors associated with the number and size of renal

angiomyolipomas in sporadic angiomyolipoma (sAML): a study

of adult patients with sAML managed in a Dutch tertiary referral

center. Int Urol Nephrol. 2018;50:459-67. Crossref

7. Wang C, Li X, Peng L, Gou X, Fan J. An update on recent developments in rupture of renal angiomyolipoma. Medicine

(Baltimore). 2018;97:e0497. Crossref

8. Flum AS, Hamoui N, Said MA, Yang XJ, Casalino DD, McGuire BB, et al. Update on the diagnosis and management of

renal angiomyolipoma. J Urol. 2016;195:834-46. Crossref

9. Kothary N, Soulen MC, Clark TW, Wein AJ, Shlansky-Goldberg RD, Crino PB, et al. Renal angiomyolipoma: long-term results after

arterial embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16:45-50. Crossref

10. Lenton J, Kessel D, Watkinson AF. Embolization of renal angiomyolipoma: immediate complications and long-term

outcomes. Clin Radiol. 2008;63:864-70. Crossref

11. Yamakado K, Tanaka N, Nakagawa T, Kobayashi S, Yanagawa M,

Takeda K. Renal angiomyolipoma: relationships between tumor

size, aneurysm formation, and rupture. Radiology. 2002;225:78-82. Crossref

12. Chatziioannou A, Gargas D, Malagari K, Kornezos I, Ioannidis I,

Primetis E, et al. Transcatheter arterial embolization as therapy of

renal angiomyolipomas: the evolution in 15 years of experience.

Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:2308-12. Crossref

13. Combes A, McQueen S, Palma CA, Benz D, Leslie S, Sved P, et al.

Is size all that matters? New predictors of complications and

bleeding in renal angiomyolipoma. Res Rep Urol. 2023;15:113-21. Crossref

14. Xu XF, Hu XH, Zuo QM, Zhang J, Xu HY, Zhang Y. A scoring

system based on clinical features for the prediction of sporadic renal

angiomyolipoma rupture and hemorrhage. Medicine (Baltimore).

2020;99:e20167. Crossref

15. Rimon U, Duvdevani M, Garniek A, Golan G, Bensaid P, Ramon J, et al. Large renal angiomyolipomas: digital subtraction

angiographic grading and presentation with bleeding. Clin Radiol.

2006;61:520-6. Crossref

16. Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Finet J, Fillion-Robin JC,

Pujol S, et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for

the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn Reson Imaging.

2012;30:1323-41. Crossref

17. Han YM, Kim JK, Roh BS, Song HY, Lee JM, Lee YH, et al. Renal

angiomyolipoma: selective arterial embolization—effectiveness

and changes in angiomyogenic components in long-term follow-up.

Radiology. 1997;204:65-70. Crossref

18. Fittschen A, Wendlik I, Oeztuerk S, Kratzer W, Akinli AS, Haenle MM, et al. Prevalence of sporadic renal angiomyolipoma:

a retrospective analysis of 61,389 in- and out-patients. Abdom

Imaging. 2014;39:1009-13. Crossref

Clinical and Imaging Outcomes of Radiosynoviorthesis in Haemophilic Arthropathy

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Hong Kong J Radiol 2025 Dec;28(4):e243-9 | Epub 9 December 2025

Clinical and Imaging Outcomes of Radiosynoviorthesis in

Haemophilic Arthropathy

KH Chu1, FY Wan1, L Xu1, TWY Chin1, IWC Wong2, CP Lam3, JSM Lau3, MK Chan1, KC Lai1

1 Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Nuclear Medicine Unit, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr KH Chu, Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR,

China. Email: ckh975@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 12 December 2024; Accepted: 9 May 2025.

Contributors: KHC and KCL designed the study. All authors acquired and analysed the data. KHC, FYW and LX drafted the manuscript. FYW,

LX, TWYC, IWCW, CPL, JSML, MKC and KCL critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access

to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This research was approved by the Central Institutional Review Board of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: CIRB-2024-113-1). A waiver of informed consent was obtained from the Board due to the retrospective nature of the study, with strict protections in

place to ensure patient privacy and the anonymity of personal data.

Abstract

Introduction

Radiosynoviorthesis, the intra-articular injection of radionuclides, is an established treatment for

haemophilic arthropathy. This study aimed to examine the clinical and imaging outcomes of radiosynoviorthesis

in Hong Kong.

Methods

A retrospective review of the radiosynoviorthesis cases performed from 2014 to 2023 in our tertiary

referral centre was conducted. Patients’ demographics, involved joints, injected radionuclides, technical success,

complications, and clinical outcomes (symptoms and frequency of bleeding) were assessed.

Results

Radiosynoviorthesis was performed on 47 joints (22 knees, 14 elbows, 8 ankles, 2 hips, and 1 shoulder) in

26 patients. Joint injections were performed under fluoroscopic or ultrasound guidance, with a technical success

rate of 98%. Six (13%) joints showed mild systemic absorption, and two (4%) joints developed transient radiation

synovitis. No major complications were encountered. Excellent clinical outcomes were observed, with 83% of cases

demonstrating symptomatic improvement and 91% showing a reduction in bleeding frequency. The mean monthly

bleeding frequency decreased from 2.2 episodes before the procedure to 0.6 episode afterwards (p = 0.005). The

total number of hospitalisations or outpatient clinic visits due to haemarthrosis decreased from 60 to 31 in the year

following the procedure (p = 0.01).

Conclusion

Our case series suggests that radiosynoviorthesis is a safe and effective procedure that can improve

clinical symptoms and reduce bleeding frequency in haemophilic arthropathy. It should be considered as part of a

multidisciplinary management approach.

Key Words: Hemarthrosis; Hemophilia A; Injections; Knee; Radiotherapy

中文摘要

血友病性關節病放射性滑膜切除術的臨床和影像學結果

朱僑栩、尹芳盈、徐璐、錢永恩、黃偉宗、林靖邦、劉詩敏、陳文光、黎國忠

引言

放射性滑膜切除術,即關節內注射放射性核素,是治療血友病性關節病的成熟方法。本研究旨在探討放射性滑膜切除術在香港的臨床與影像學成效。

方法

本研究回顧分析了本中心於2014至2023年間進行的放射性滑膜切除術病例。評估內容包括患者的人口學特徵、受累關節、注射的放射性核素種類、技術成功率、併發症,以及臨床療效(症狀及出血頻率)。

結果

共為26位患者的47個關節(包括22個膝關節、14個肘關節、8個踝關節、2個髖關節及1個肩關節)進行放射性滑膜切除術。關節注射在透視或超聲影像引導下進行,技術成功率達98%。其中6個關節(13%)出現輕微的全身性放射性物質吸收,兩個關節(4%)出現短暫性放射性滑膜炎,未見重大併發症。臨床效果理想,83%病例症狀有所改善,91%病例出血頻率下降。平均每月出血次數由術前的2.2次顯著下降至術後的0.6次(p = 0.005)。術後一年內因關節積血而導致的住院及門診就診總次數由60次減少至31次(p = 0.01)。

結論

本病例系列顯示,放射性滑膜切除術是安全且有效的治療方式,能改善血友病性關節病患者的臨床症狀並降低出血頻率,應納入多學科綜合治療方案。

INTRODUCTION

Patients with haemophilia and von Willebrand disease

show an increased tendency to bleed. These patients can

present with recurrent haemarthrosis.[1] The synovium

becomes hypertrophied due to the inflammatory

response to iron deposition within the joint.[2] Increased

vascularity in the inflamed synovium renders it more

prone to bleeding. This creates a vicious cycle, leading to

cartilage and bone damage and resulting in arthropathy.

Prevention and treatment of musculoskeletal damage are

paramount in the care of patients with bleeding disorders.

Prophylactic measures include coagulation factor

replacement therapy and subcutaneous emicizumab

injections to reduce bleeding and prevent subsequent

haemarthropathy.[3] These measures have provided

greater protection for patients and significantly improved

patients’ quality of life. However, recurrent haemarthrosis

remains an issue for some patients despite advances in

medical treatments.[3] In the past, surgical synovectomy

was employed in patients who failed to respond to

medical treatment.[4] Over time, more studies have

reported favourable clinical outcomes with non-surgical

synovectomy, which includes intra-articular injection of

radioisotopes (radiosynoviorthesis) or antibiotics such as rifampicin.[1] [5] [6] [7] These minimally invasive interventions

have gained popularity and are now considered viable

alternatives to surgery.[8] [9] Surgery is reserved for cases

when intra-articular injections are unsuccessful.

Radiosynoviorthesis, also referred to radiation

synovectomy, involves the injection of radionuclides

into affected joints, leading to fibrosis of the inflamed

and hypertrophied synovium.[10] The primary objectives

of this treatment are to reduce bleeding frequency and

alleviate clinical symptoms such as pain and swelling.

Once absorbed by the synovium, the radionuclides emit

high-energy beta particles that induce cell death and

obliterate the capillary blood supply.[11] This results in

fibrosis and sclerosis of the synovial membrane, as well

as a significant decrease in inflammatory activity and

angiogenesis, ultimately reducing the bleeding tendency.

Although international guidelines and studies are

available for Western populations, there remains a

limited focus on Asian haemophilic patients and our

local population.[12] [13] In this retrospective study, we aimed

to evaluate the technical success, efficacy, and safety

of radiosynoviorthesis in our tertiary referral centre in

Hong Kong.

METHODS

All cases of radiosynoviorthesis performed on patients

with haemophilic arthropathy in Queen Elizabeth

Hospital between 2014 and 2023 were retrospectively

reviewed. Data were collected on patient demographics,

type of bleeding disorder, joints treated, radionuclides

administered, technical success, clinical outcomes, and

complications.

Technical success was defined as successful joint

puncture and intra-articular injection of radionuclides,

confirmed by postprocedural scintigraphy. Clinical

outcomes were assessed by evaluating patient records

for changes in joint pain, swelling, and bleeding

frequency. As transient synovitis could cause temporary

symptoms following the procedure, patients’ symptoms

were evaluated at least 3 months afterwards. Clinical

assessments were performed during follow-up visits 6

to 12 months post procedure. Bleeding frequency was

compared by analysing the monthly bleeding episodes

before the procedure and 12 months after the procedure.

The number of hospitalisations or outpatient clinic

appointments due to haemarthrosis during the same

period was also recorded. Comparisons were analysed

using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Techniques

Patients with disturbing pain and recurrent haemarthrosis

(defined as three or more bleeding episodes in the

same joint over 6 months) despite medical treatment,

and with clinical or radiological evidence of synovitis,

were considered indicated for radiosynoviorthesis

and referred by haematologists.[10] Initial evaluation

was conducted by nuclear medicine physicians.

Contraindications included pregnancy, breastfeeding,

or local skin infection at the targeted joint.[14] Relative

contraindications included severe joint instability, bony

destruction, or significant cartilage loss. Preprocedural

imaging, including X-rays, ultrasound, and/or magnetic

resonance imaging, was used to assess the severity of

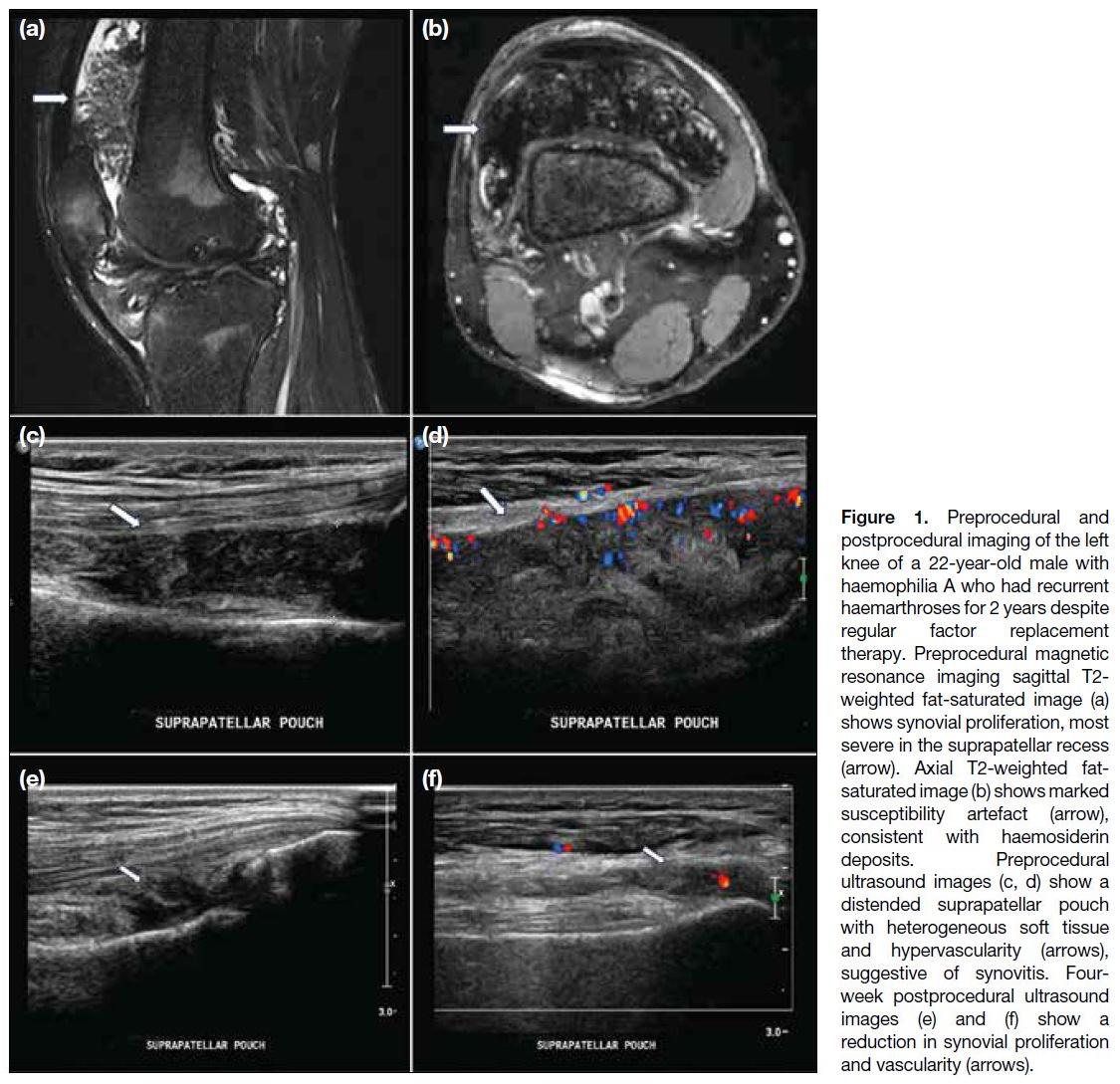

synovitis and arthropathy (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Preprocedural and

postprocedural imaging of the left knee of a 22-year-old male with haemophilia A who had recurrent haemarthroses for 2 years despite regular factor replacement therapy. Preprocedural magnetic resonance imaging sagittal T2-weighted fat-saturated image (a) shows synovial proliferation, most severe in the suprapatellar recess (arrow). Axial T2-weighted fat-saturated image (b) shows marked susceptibility artefact (arrow), consistent with haemosiderin deposits. Preprocedural ultrasound images (c, d) show a distended suprapatellar pouch with heterogeneous soft tissue and hypervascularity (arrows), suggestive of synovitis. Four-week postprocedural ultrasound images (e) and (f) show a reduction in synovial proliferation and vascularity (arrows).

The choice of radionuclides was based on the size of the

joint and required tissue penetration. Two beta-emitting

isotopes were used, namely, yttrium-90 (90Y) and

rhenium-186 (186Re).[15] These isotopes exhibit different

physical characteristics. 90Y, with a maximum beta

energy of 2.26 MeV and a mean tissue penetration of

3.6 mm, was used for knee joint. 186Re, with a maximum

beta energy of 0.98 MeV and a mean penetration of 1.2

mm, was employed for medium-sized joints including the hip, shoulder, elbow, and ankle. Doses ranged from

4.4 to 5.2 mCi (162.8-192.4 MBq) of 90Y for knees, 2.1

to 2.2 mCi (77.7-81.4 MBq) of 186Re for ankles, and

5.3 mCi (196.1 MBq) of 186Re for shoulders and hips.

All procedures were performed in ambulatory setting.

Under ultrasound or fluoroscopic guidance, the joint was

punctured, and contrast medium was injected to confirm

intra-articular location. The radionuclide was then

administered, along with a long-acting corticosteroid

such as triamcinolone acetonide, to reduce the risk of

radiation-induced synovitis and minimise leakage.[11] The

needle tract was flushed with saline during withdrawal to

prevent radiation necrosis of the puncture site.

After the procedure, the affected joint was immobilised

for 48 hours using a splint to reduce the risk of leakage

into surrounding tissues.[16] Bremsstrahlung imaging was

employed within 24 hours to confirm intra-articular

distribution of the radiopharmaceutical. Patients were

counselled on hygiene precautions due to urinary

excretion of the radionuclide. They were instructed to

flush the toilet twice after each use, wash their hands

thoroughly, avoid soiling underclothing or areas around

the toilet bowl, and wash any soiled garments separately.

Clinical follow-up was carried out by haematologists.

RESULTS

A total of 26 male patients, aged between 10 and 57

years (median, 35), underwent radiosynoviorthesis

during the study period (Table). The mean duration of

follow-up was 76 months (range, 10-116). Among them,

23 patients had haemophilia A, two had haemophilia B,

and one had von Willebrand disease. A total of 47 joints

were injected: 22 (47%) knees, 14 (30%) elbows, eight

(17%) ankles, two (4%) hips, and one (2%) shoulder.

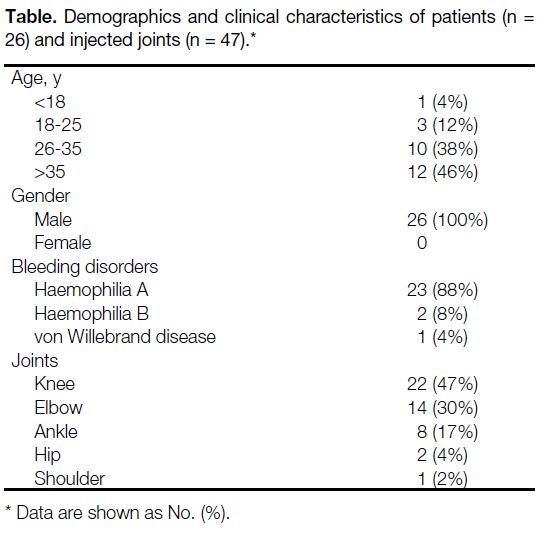

Table. Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients (n = 26) and injected joints (n = 47).

Technical success was achieved in 46 (98%) out of the

47 joints. In one case, the right hip joint could not be

accessed due to advanced degenerative changes.

Improvement in symptoms, specifically pain

and swelling, was observed in 38 (83%) joints

(95% confidence interval [95% CI] = 69%-92%).

Eight (17%) joints showed no change in symptoms

(95% CI = 8%-31%), and no joint demonstrated

worsening. Three patients experienced partial symptom

relief after the first injection and subsequently underwent

a second injection 6 months later, after which all

reported further improvement. Although routine

follow-up imaging was not conducted for every patient, ultrasound in selected cases showed reduced synovial

proliferation and vascularity, indicating improvement

(Figure 1).

A reduction in bleeding frequency was noted in 42

(91%) joints (95% CI = 79%-98%), while four (9%)

joints showed no change (95% CI = 2%-21%). No

joint exhibited increased bleeding frequency. The mean

monthly bleeding frequency decreased from 2.2 episodes

(range, 0.5-6) before the procedure to 0.6 episode

(range, 0-4) afterwards (p = 0.005). Hospitalisations and

outpatient clinic visits due to haemarthrosis decreased from 60 to 31 in the year following the procedure (p = 0.01).

There were no major complications or procedure-related

mortality. There were no documented cases of bleeding,

infection, or necrosis.[17] [18] Minor complications or side-effects

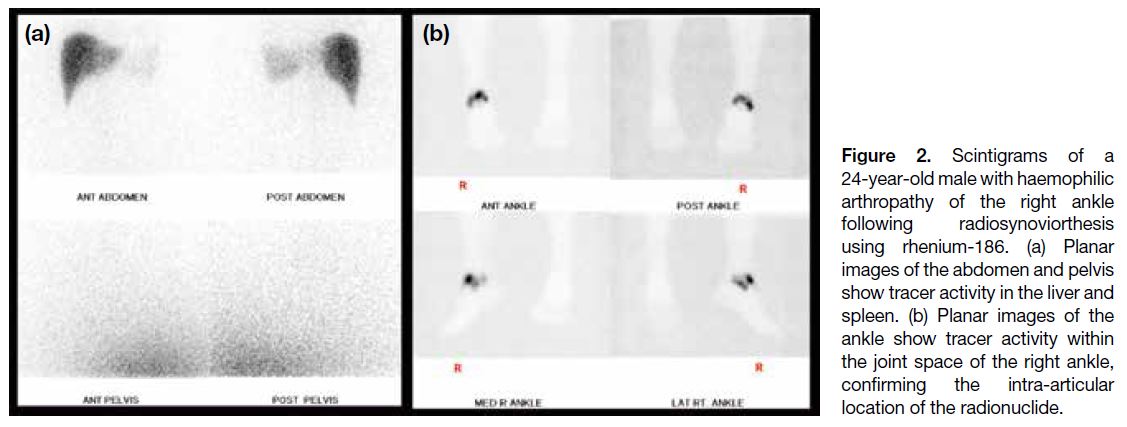

were observed in eight cases. Six (13%) joints

showed postprocedural scintigraphic uptake in the liver

and spleen, suggestive of systemic absorption (95% CI = 5%-26%) [Figure 2]. Liver function tests during follow-up

were normal, and these patients still experienced

clinical improvement.

Figure 2. Scintigrams of a

24-year-old male with haemophilic

arthropathy of the right ankle

following radiosynoviorthesis

using rhenium-186. (a) Planar

images of the abdomen and pelvis

show tracer activity in the liver and

spleen. (b) Planar images of the

ankle show tracer activity within

the joint space of the right ankle,

confirming the intra-articular

location of the radionuclide.

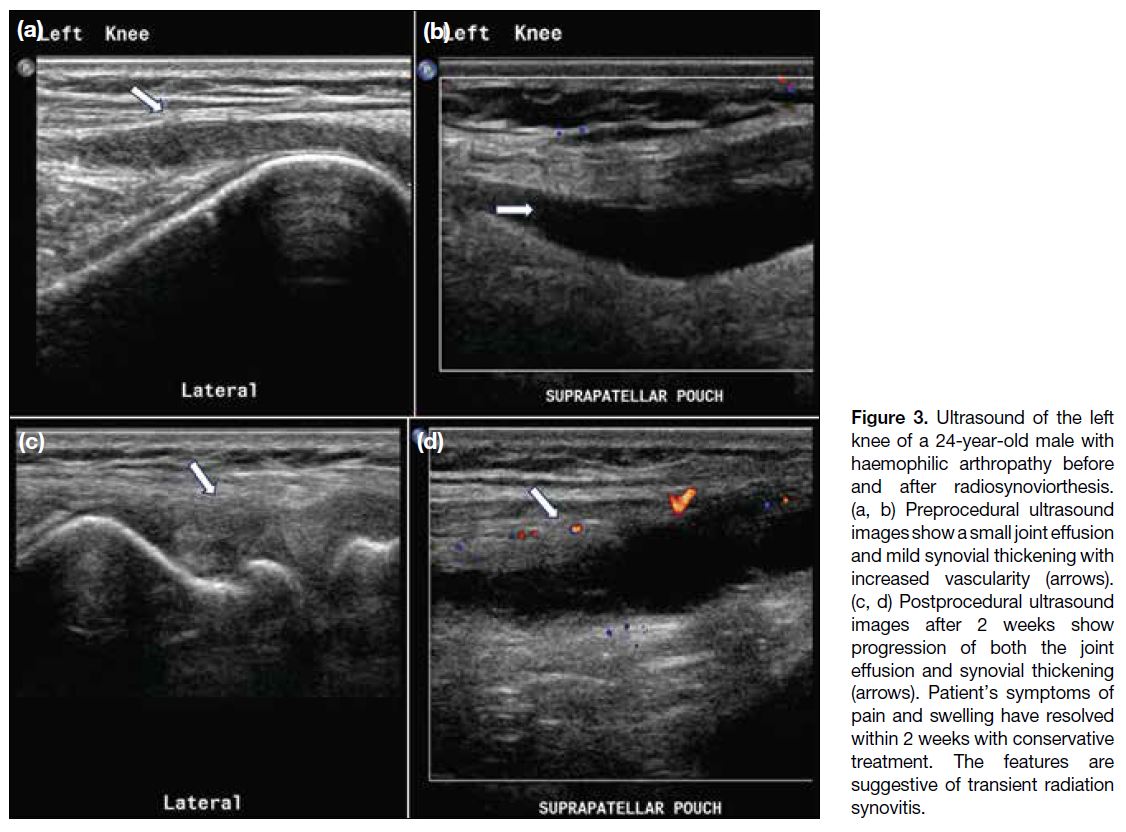

Two (4%) joints developed transient radiation

synovitis (95% CI=0.5%-15%), characterised by pain

and swelling shortly after the procedure. Ultrasound

confirmed increased joint effusion and synovitis (Figure 3). These symptoms resolved within 2 weeks following

conservative treatment with ice packs and nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs.

Figure 3. Ultrasound of the left

knee of a 24-year-old male with

haemophilic arthropathy before

and after radiosynoviorthesis.

(a, b) Preprocedural ultrasound

images show a small joint effusion

and mild synovial thickening with

increased vascularity (arrows).

(c, d) Postprocedural ultrasound

images after 2 weeks show

progression of both the joint

effusion and synovial thickening

(arrows). Patient’s symptoms of

pain and swelling have resolved

within 2 weeks with conservative

treatment. The features are

suggestive of transient radiation

synovitis.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that most patients with bleeding

disorders and recurrent haemarthrosis responded well

to radiosynoviorthesis. Our findings are consistent with previous international studies. A systematic review

and a meta-analysis reported an overall response rate

of 72.5%.[19] Radiosynoviorthesis can be performed in

paediatric patients with appropriate selection and dosage

adjustment,[20] as shown by the successful treatment of

a 10-year-old in our cohort. It offers the advantages of

reduced hospital stays and lower costs compared with

surgical synovectomy. Moreover, it can be repeated up to

three times per joint, with intervals of at least 6 months.[21]

It can be difficult to perform intra-articular injection,

particularly in patients with severely deformed joints.

According to the literature, the best clinical improvement

was identified in patients with high inflammatory

activity in an early phase of arthropathy.[22] Therefore,

this procedure is expected to have maximal benefit in

patients in the earlier stages of arthropathy.

Radiosynoviorthesis is well tolerated, with a low

incidence of side-effects or complications. Extra-articular

activity was uncommon and was not accompanied by

clinically significant side-effects. Direct leakage out of

the joint space was rare, but systemic absorption could

occur due to uptake by the lymphatic circulation and,

subsequently, the bloodstream. This may be reduced by

immobilisation of the joints. Patients were encouraged

to increase their fluid intake and to void frequently.

Two patients experienced radiation-induced synovitis in

our review. It was a clinical manifestation of rapid and

extensive synovial tissue necrosis that can occur 6 to

48 hours after the procedure.[23] The joint pain, swelling,

and effusion are usually self-limiting and can be treated

conservatively by cooling the joint with ice packs and, if necessary, with anti-inflammatory drugs. Intra-articular

corticosteroid injection during the procedure can reduce

inflammation and decrease leakage of the radioisotope

through dilated capillaries of the synovium into the

systemic circulation.

Limitations

There are several limitations in this study. First, it

was retrospective in nature, with a relatively small

cohort size, and no control arm was available for

comparison. Nonetheless, this study still offered

results in our local population that were in line with

other studies demonstrating the efficacy and safety of

radiosynoviorthesis.[5] [6] [7] [10] [22] Another limitation was the

heterogeneous study population, with different joints

involved and varying severity of arthropathy. In general,

most patients still showed favourable clinical outcomes.

Subgroup analysis may be considered in the future with

a larger number of patients.

There was no objective pain scoring system in place to

provide a quantitative assessment of clinical symptoms,

nor was there a standardised magnetic resonance imaging

protocol to exclude patients with severe cartilage loss or

degenerative joint conditions that could contribute to

pain. A prospective study would be ideal for recruiting

patients and conducting assessments using an objective

scoring system for symptoms and a standard follow-up

protocol. Radiological investigations, such as ultrasound,

can be used to assess for synovitis and serve as another

objective parameter in evaluating outcomes. This

approach would also facilitate longitudinal comparisons

to investigate long-term efficacy and allow monitoring

of disease progression. Lastly, there may be potential

confounders such as the co-injection of steroid with the

radionuclides. The use of steroids may have caused a

period of analgesia and helped bridge the gap between

the administration of the radiopharmaceutical and the

onset of the effects of radiosynoviorthesis. However, such an effect was expected to be short term and unlikely

to persist beyond 3 months, when our clinical assessment

was conducted.

CONCLUSION

Radiosynoviorthesis is a safe and effective procedure

which can contribute to symptomatic improvement

and a reduction in bleeding frequency in patients with

haemophilic arthropathy. It should be considered as part

of a multidisciplinary management approach.

REFERENCES

1. van Galen KP, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, Leebeek FW. Hemophilic

arthropathy in patients with von Willebrand disease. Blood Rev.

2012;26:261-6. Crossref

2. Hoots WK, Rodriguez N, Boggio L, Valentino LA. Pathogenesis

of haemophilic synovitis: clinical aspects. Haemophilia. 2007;13

Suppl 3:4-9. Crossref

3. Oldenburg J. Optimal treatment strategies for hemophilia:

achievements and limitations of current prophylactic regimens.

Blood. 2015;125:2038-44. Crossref

4. Llinás A. The role of synovectomy in the management of a target

joint. Haemophilia. 2008;14 Suppl 3:177-80. Crossref

5. Querol-Giner M, Pérez-Alenda S, Aguilar Rodríguez M,

Carrasco JJ, Bonanad S, Querol F. Effect of radiosynoviorthesis

on the progression of arthropathy and haemarthrosis reduction in

haemophilic patients. Haemophilia. 2017;23:e497-503. Crossref

6. Desaulniers M, Paquette M, Dubreuil S, Senta H, Lavallée É,

Thorne JC, et al. Safety and efficacy of radiosynoviorthesis: a

prospective Canadian multicenter study. J Nucl Med. 2024;65:1095-100. Crossref

7. Kavakli K, Aydoğdu S, Omay SB, Duman Y, Taner M, Capaci K,

et al. Long-term evaluation of radioisotope synovectomy with

yttrium 90 for chronic synovitis in Turkish haemophiliacs: Izmir

experience. Haemophilia. 2006;12:28-35. Crossref

8. van Vulpen LF, Thomas S, Keny SA, Mohanty SS. Synovitis and

synovectomy in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2021;27 Suppl 3:96-102. Crossref

9. Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Wiedel JD. General principles

and indications of synoviorthesis (medical synovectomy) in

haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2001;7 Suppl 2:6-10. Crossref

10. Kampen WU, Boddenberg-Pätzold B, Fischer M, Gabriel M, Klett R, Konijnenberg M, et al. The EANM guideline for

radiosynoviorthesis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022;49:681-708. Crossref

11. Fischer M, Mödder G. Radionuclide therapy of inflammatory joint diseases. Nucl Med Commun. 2002;23:829-31. Crossref

12. Hanley J, McKernan A, Creagh MD, Classey S, McLaughlin P,

Goddard N, et al. Guidelines for the management of acute joint

bleeds and chronic synovitis in haemophilia: A United Kingdom

Haemophilia Centre Doctors’ Organisation (UKHCDO) guideline.

Haemophilia. 2017;23:511-20. Crossref

13. Srivastava A, Santagostino E, Dougall A, Kitchen S, Sutherland M,

Pipe SW, et al. WFH Guidelines for the Management of

Hemophilia, 3rd edition. Haemophilia. 2020;26 Suppl 6:1-158. Crossref

14. Chojnowski MM, Felis-Giemza A, Kobylecka M. Radionuclide

synovectomy—essentials for rheumatologists. Reumatologia.

2016;54:108-16. Crossref

15. Knut L. Radiosynovectomy in the therapeutic management of arthritis. World J Nucl Med. 2015;14:10-5. Crossref

16. Ahmad I, Nisar H. Dosimetry perspectives in radiation synovectomy. Phys Med. 2018;47:64-72. Crossref

17. Kampen WU, Matis E, Czech N, Soti Z, Gratz S, Henze E. Serious

complications after radiosynoviorthesis. Survey on frequency and

treatment modalities. Nuklearmedizin. 2006;45:262-8. Crossref

18. Infante-Rivard C, Rivard GE, Derome F, Cusson A, Winikoff R,

Chartrand R, et al. A retrospective cohort study of cancer incidence

among patients treated with radiosynoviorthesis. Haemophilia.

2012;18:805-9. Crossref

19. van der Zant FM, Boer RO, Moolenburgh JD, Jahangier ZN,

Bijlsma JW, Jacobs JW. Radiation synovectomy with (90)yttrium,

(186)rhenium and (169)erbium: a systematic literature review with

meta-analyses. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27:130-9.

20. Manco-Johnson MJ, Nuss R, Lear J, Wiedel J, Geraghty SJ,

Hacker MR, et al. 32P radiosynoviorthesis in children with

hemophilia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002;24:534-9. Crossref

21. Clunie G, Fischer M; EANM. EANM procedure guidelines for radiosynovectomy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:BP12-6. Crossref

22. Kresnik E, Mikosch P, Gallowitsch HJ, Jesenko R, Just H,

Kogler D, et al. Clinical outcome of radiosynoviorthesis: a

meta-analysis including 2190 treated joints. Nucl Med Commun.

2002;23:683-8. Crossref

23. Pirich C, Schwameis E, Bernecker P, Radauer M, Friedl M,

Lang S, et al. Influence of radiation synovectomy on articular

cartilage, synovial thickness and enhancement as evidenced by MRI

in patients with chronic synovitis. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1277-84.

CASE REPORT

Intracranial Neuroendocrine Tumour of Unknown Origin Mimicking Neurocysticercosis: A Case Report

CASE REPORT

Hong Kong J Radiol 2025 Dec;28(4):e250-6 | Epub 10 December 2025

Intracranial Neuroendocrine Tumour of Unknown Origin

Mimicking Neurocysticercosis: A Case Report

CW Chan, KO Cheung, CY Cheung

Department of Radiology, North District Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr CW Chan, Department of Radiology, North District Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: ccw147@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 3 December 2024; Accepted: 11 April 2025.

Contributors: All authors designed the study. CWC acquired and analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised

the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for

publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and provided verbal consent for publication of this case

report, including the accompanying clinical images.

INTRODUCTION

Neuroendocrine tumours of the central nervous system

are relatively rare entities and most cases are metastases.

Primary intracranial neuroendocrine tumour is even rarer,

with fewer than a dozen cases reported worldwide.[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8]

Apart from a case report on a 5-year-old child,[9] all

reported primary cases have been in adults. The location

of lesions reported varies greatly. Reported extra-axial

locations include, but are not limited to, the

cerebellopontine angle, jugular foramen, cavernous

sinus, and skull base. Reported intra-axial locations include the left temporal and parietal lobes, as well as the left

cerebellum. We report a case of neuroendocrine tumour

of unknown origin with multiple intracranial metastases.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 56-year-old woman with good past health presented to

the accident and emergency department with dizziness

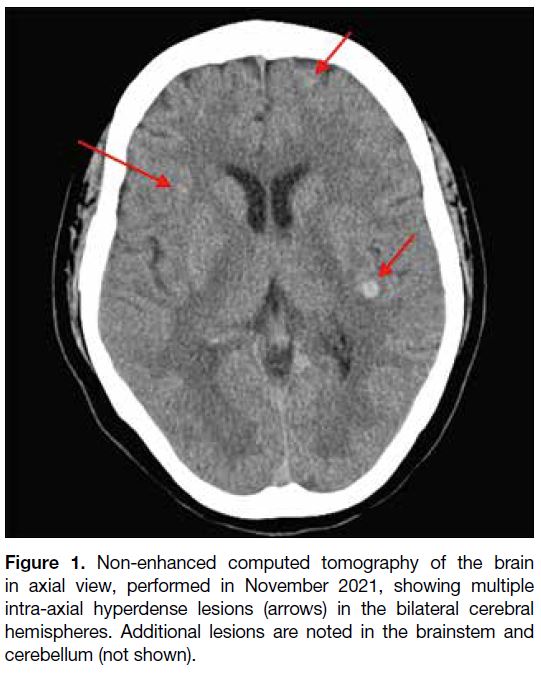

in October 2021. Initial computed tomography of the

brain revealed multiple hyperdense lesions scattered

across both cerebral hemispheres, the brainstem, and the

cerebellum (Figure 1). Whole-body positron emission

tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) did not reveal any

primary malignancy elsewhere that could suggest brain

metastases. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance

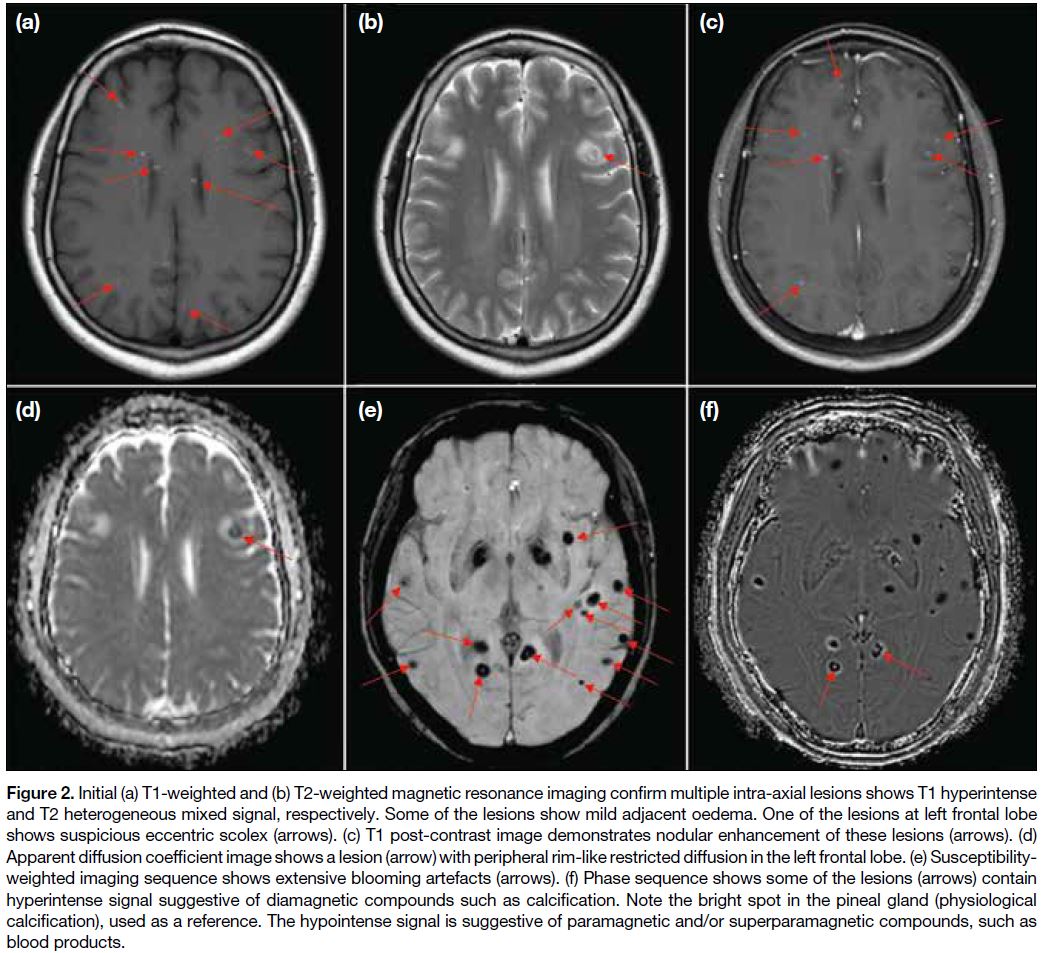

imaging (MRI) of the brain was performed to

characterise the intracranial lesions (Figure 2). The

corresponding cerebral, brainstem, and cerebellar lesions

showed T1 hyperintense and T2 heterogeneous mixed

signals. Most lesions showed susceptibility artefacts,

while some showed a signal on the phase sequence

characteristic of calcification. Overall features were

suggestive of concurrent haemorrhagic and calcified

lesions. Some lesions also showed eccentric nodular

enhancement. One 7-mm lesion in the left frontal lobe demonstrated restricted diffusion and a suspicious eccentric scolex (Figure 2b). In view of the previously

negative whole-body PET-CT, the possibility of central

nervous system infection with neurocysticercosis in

different stages was considered a likely possibility. A

differential diagnosis of haemorrhagic/calcified brain

metastases appeared less likely. Serology testing for

Taenia solium was negative, but given the radiological

appearance of neurocysticercosis, the patient was

prescribed a course of albendazole and praziquantel, as

well as dexamethasone to minimise cerebral oedema.

Figure 1. Non-enhanced computed tomography of the brain

in axial view, performed in November 2021, showing multiple

intra-axial hyperdense lesions (arrows) in the bilateral cerebral

hemispheres. Additional lesions are noted in the brainstem and

cerebellum (not shown).

Figure 2. Initial (a) T1-weighted and (b) T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging confirm multiple intra-axial lesions shows T1 hyperintense

and T2 heterogeneous mixed signal, respectively. Some of the lesions show mild adjacent oedema. One of the lesions at left frontal lobe

shows suspicious eccentric scolex (arrows). (c) T1-weighted post-contrast image demonstrates nodular enhancement of these lesions (arrows). (d)

Apparent diffusion coefficient image shows a lesion (arrow) with peripheral rim-like restricted diffusion in the left frontal lobe. (e) Susceptibility-weighted

imaging sequence shows extensive blooming artefacts (arrows). (f) Phase sequence shows some of the lesions (arrows) contain

hyperintense signal suggestive of diamagnetic compounds such as calcification. Note the bright spot in the pineal gland (physiological

calcification), used as a reference. The hypointense signal is suggestive of paramagnetic and/or superparamagnetic compounds, such as

blood products.

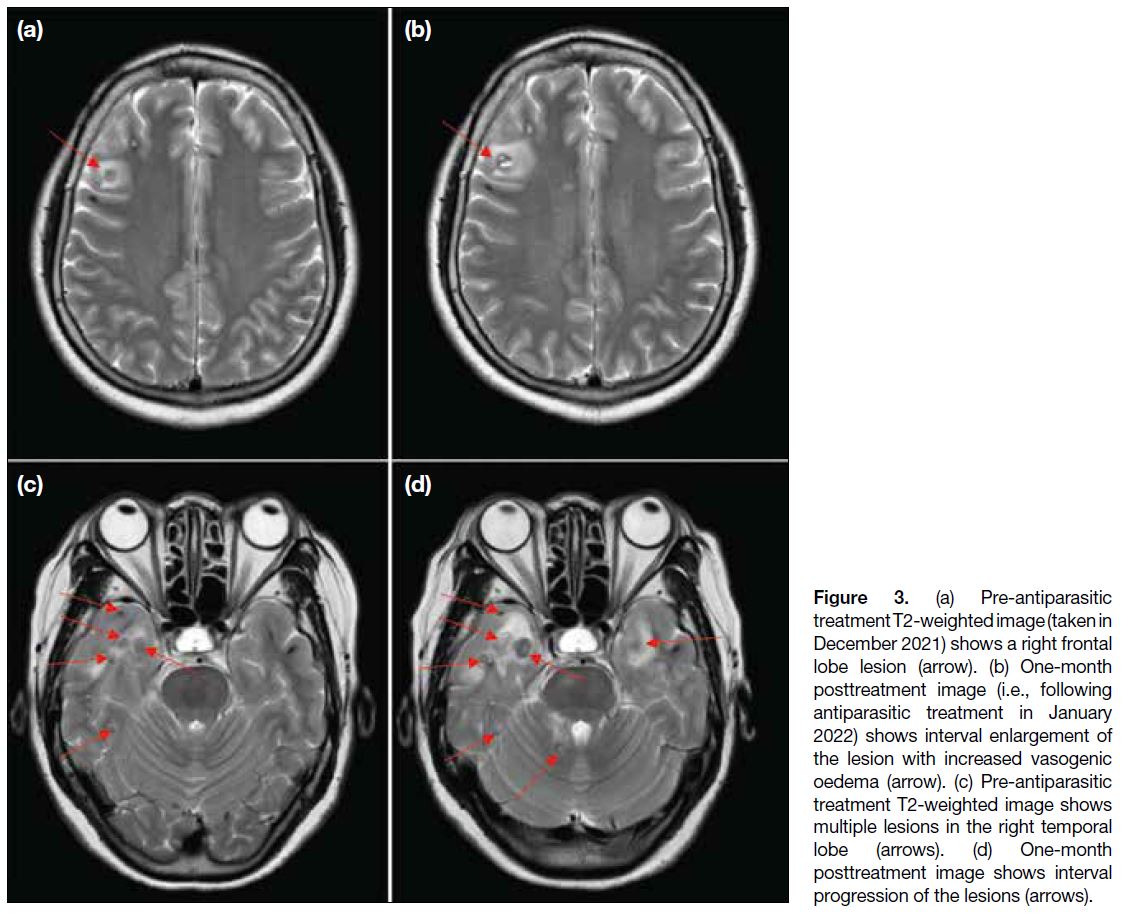

Multiple follow-up MRI scans of the brain were

performed. Initially, at 1-month post-treatment, some

lesions (particularly those at the frontal and temporal lobes) showed interval enlargement with an increase in

perilesional vasogenic oedema (Figure 3). These findings

were thought to be attributable to posttreatment change.

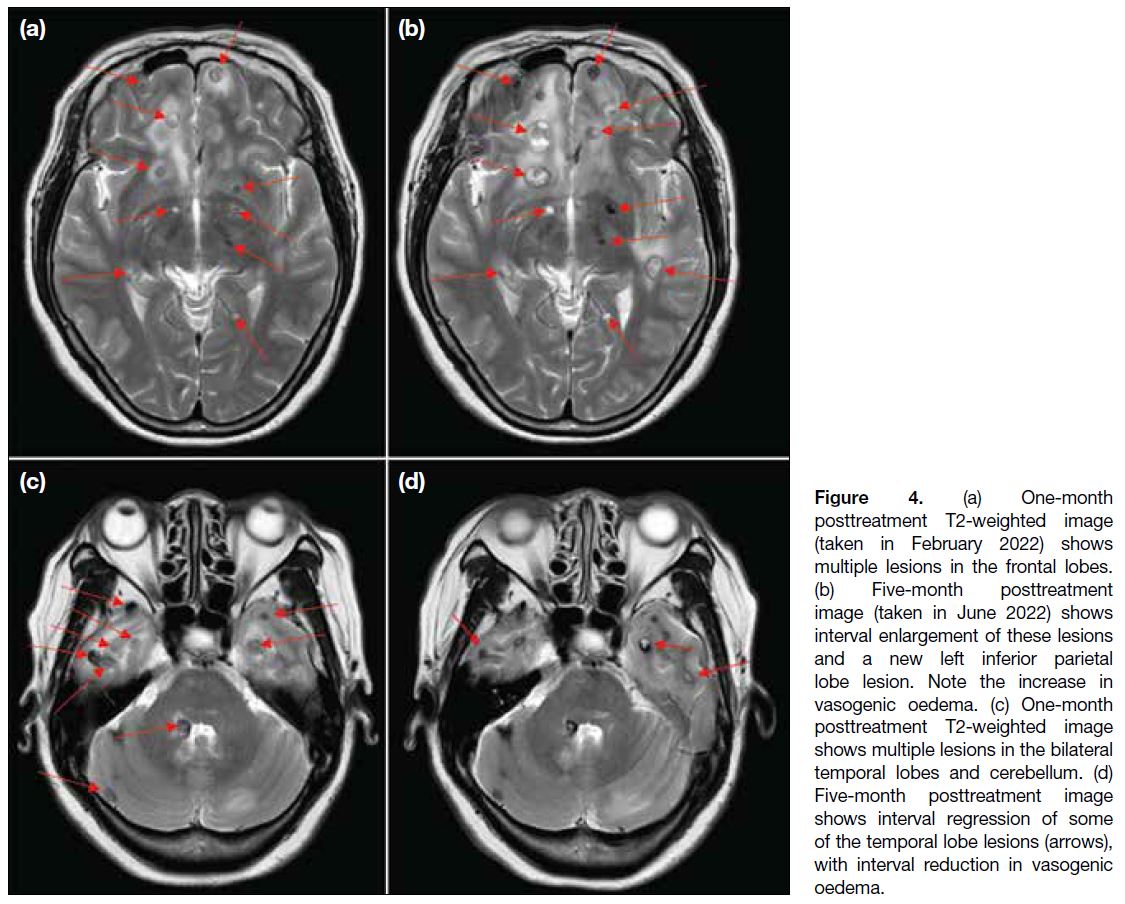

A scan at 5 months posttreatment revealed continued progression of some lesions in the bilateral frontal and left inferior parietal lobes (Figure 4a and b), while some lesions in the bilateral temporal lobes had regressed (Figure 4c and d). The overall picture favoured a mixed treatment response.

Figure 3. (a) Pre-antiparasitic

treatment T2-weighted image (taken in

December 2021) shows a right frontal

lobe lesion (arrow). (b) One-month

posttreatment image (i.e., following

antiparasitic treatment in January

2022) shows interval enlargement of

the lesion with increased vasogenic

oedema (arrow). (c) Pre-antiparasitic

treatment T2-weighted image shows

multiple lesions in the right temporal

lobe (arrows). (d) One-month

posttreatment image shows interval

progression of the lesions (arrows).

Figure 4. (a) One-month

posttreatment T2-weighted image

(taken in February 2022) shows

multiple lesions in the frontal lobes.

(b) Five-month posttreatment

image (taken in June 2022) shows

interval enlargement of these lesions

and a new left inferior parietal

lobe lesion. Note the increase in

vasogenic oedema. (c) One-month

posttreatment T2-weighted image

shows multiple lesions in the bilateral

temporal lobes and cerebellum (arrows). (d)

Five-month posttreatment image

shows interval regression of some

of the temporal lobe lesions (arrows),

with interval reduction in vasogenic

oedema.

A further course of antiparasitic treatment was given,

assuming the infection was unresolved. Nonetheless,

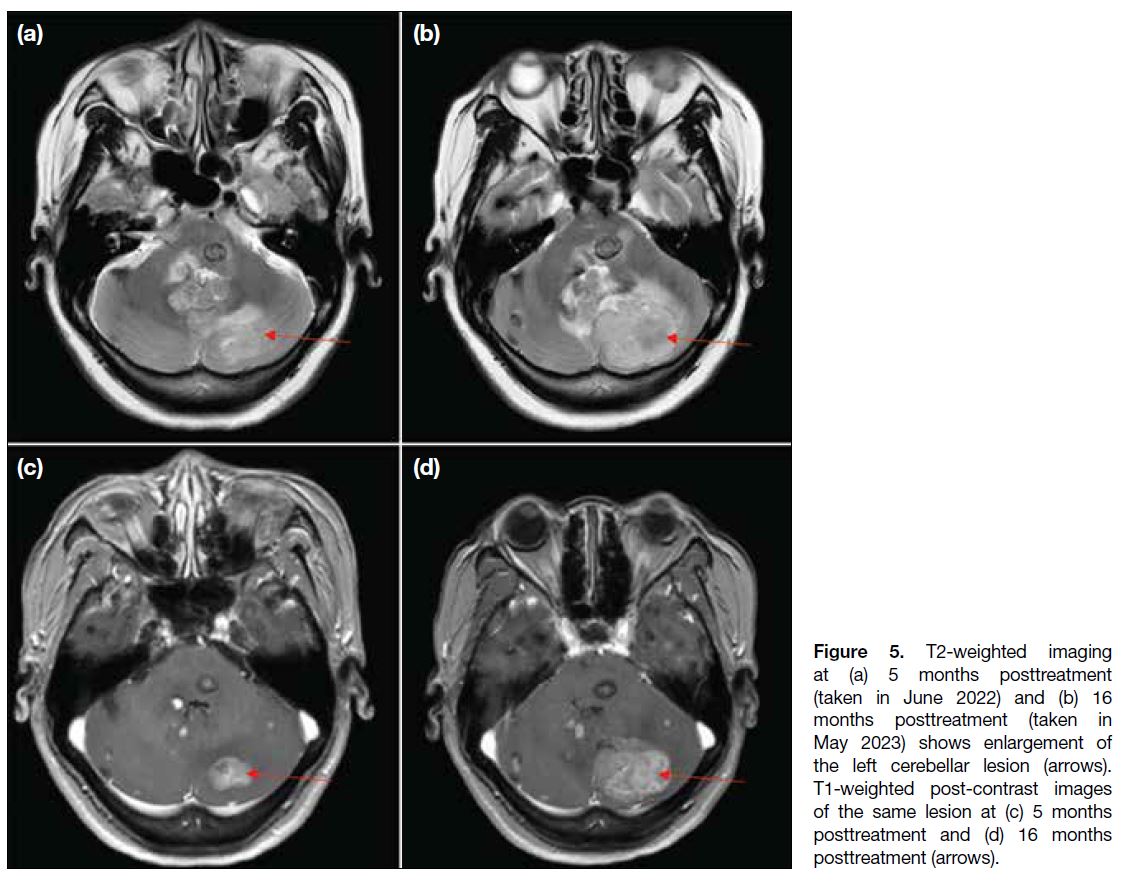

follow-up scan at 16 months after initiation of antiparasitic

treatment showed not only persistent lesions, but interval

enlargement of some (the largest at the left cerebellar

hemisphere; Figure 5), with developing obstructive

hydrocephalus. In view of the patient’s worsening

symptoms of increased intracranial pressure (headache, dizziness and vomiting), as well as imaging findings,

the neurosurgical team intervened and left posterior

craniotomy was performed for decompression and to

excise the left cerebellar lesion. An external ventricular

drain was placed. Intraoperative findings noted a large

intra-axial tumour at the left cerebellar hemisphere,

likely malignant. Pathology confirmed a grade 3

neuroendocrine tumour, with additional comment that

a metastatic lesion was likely. A repeated whole-body

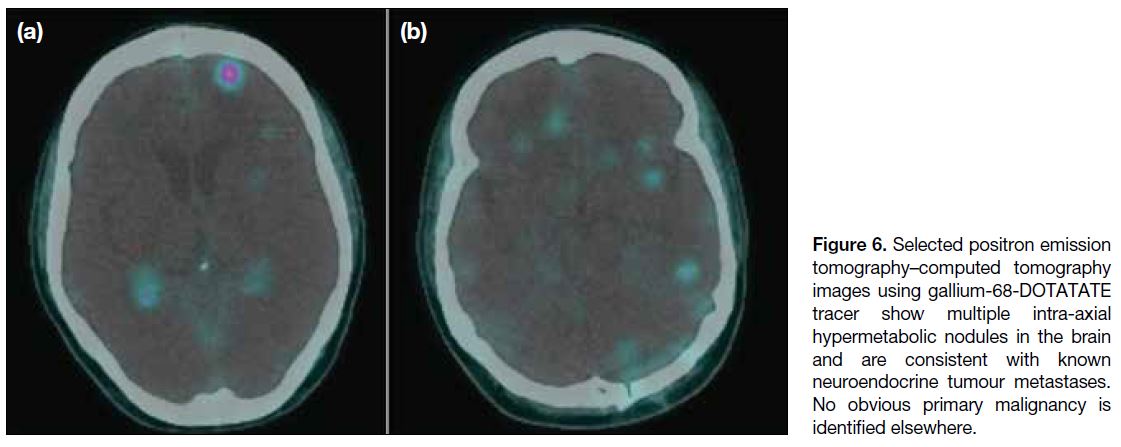

PET-CT with gallium-68-DOTA-tyr3-octreotate (Ga-68-DOTATATE) showed multiple hypermetabolic nodules

in the brain suggestive of known neuroendocrine tumour

(Figure 6), but still no obvious location for a primary

malignancy. A preliminary diagnosis was reached of

neuroendocrine tumour of unknown origin, with possible

primary within the brain. Postoperatively, the patient

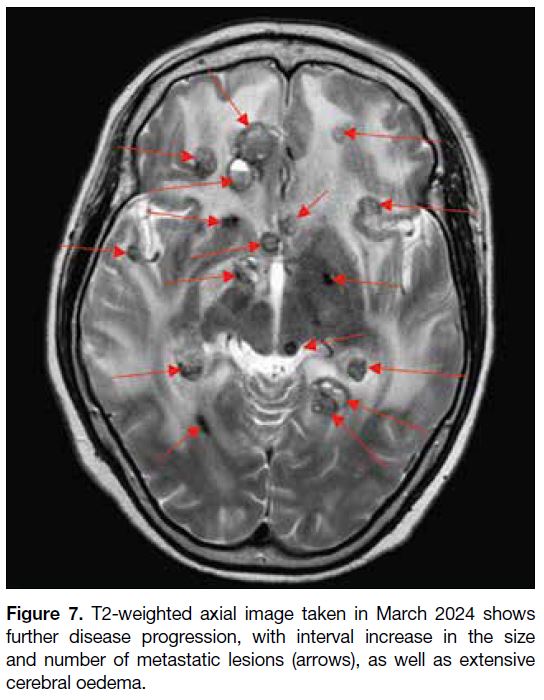

underwent further follow-up MRI scans that revealed

new suspicious drop metastasis at the C4 level, as well as significant progression of brain metastases and

worsening vasogenic oedema (Figure 7). The patient

was followed up by the neurosurgery and oncology

teams and underwent radiotherapy of the whole brain

and the cervical spinal cord as palliative care. At 35

months after the initial presentation, the patient died due

to a complication of pneumonia.

Figure 5. T2-weighted imaging

at (a) 5 months posttreatment

(taken in June 2022) and (b) 16

months posttreatment (taken in

May 2023) shows enlargement of

the left cerebellar lesion (arrows).

T1-weighted post-contrast images

of the same lesion at (c) 5 months

posttreatment and (d) 16 months

posttreatment (arrows).

Figure 6. Selected positron emission

tomography–computed tomography

images using gallium-68-DOTATATE

tracer show multiple intra-axial

hypermetabolic nodules in the brain

and are consistent with known

neuroendocrine tumour metastases.

No obvious primary malignancy is

identified elsewhere.

Figure 7. T2-weighted axial image taken in March 2024 shows

further disease progression, with interval increase in the size

and number of metastatic lesions (arrows), as well as extensive

cerebral oedema.

DISCUSSION

Neurocysticercosis and neuroendocrine tumour of the

brain are two distinct entities that require very

different treatment approaches. The patient’s presenting

signs and symptoms (such as headache, dizziness and

seizure) are often non-specific. Serology testing for

Taenia solium, while specific, is often not sensitive. A

negative serology test does not exclude the diagnosis

of neurocysticercosis; hence, it was reasonable for our patient to undergo a trial of antiparasitic treatment based

on radiological appearance alone.

Imaging plays an important role in guiding the diagnosis

as well as treatment in such difficult cases. Nonetheless,

as with our case, imaging also has its limitations and can

be misguided by disease mimics.

On MRI, neurocysticercosis has varied radiological

appearances depending on its four main stages.[10] [11]

During the vesicular stage, cysts with cerebrospinal

fluid (CSF) intensity are often seen, sometimes with an

eccentric scolex that may show enhancement. Typically,

no surrounding vasogenic oedema is seen at this stage.

Intraventricular cysts may be difficult to visualise, and

heavily T2-weighted sequences such as FIESTA (fast

imaging employing steady-state acquisition) may help delineate the walls and scolex of neurocysticercosis. In

addition, the cystic content may show a slightly lower

signal compared with CSF, making them stand out.[12] For

our case, the FIESTA sequence was not performed due

to limited resources.

During the colloidal vesicular stage, cysts will often

contain increased proteinaceous content, leading to T1

and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintense

signal relative to CSF. Thickening and enhancement of

the cyst wall, as well as surrounding oedema, may be

seen. Some lesions may also show restricted diffusion,[11]

as in our case, which further complicates the clinical picture.

During the granular nodular stage, the cystic component

will resolve, becoming a small enhancing nodule.

Contrast enhancement and perilesional oedema will

gradually decrease and eventually resolve in the final

nodular calcified stage, where calcified nodules are seen. Neuroendocrine tumour of the brain, whether primary

or secondary, can also have variable appearances

mimicking other diseases. Among the reported primary

cases, MRI appearances ranged from a

solid enhancing mass to a cystic mass with a peripheral

enhancing component.[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9]

Spontaneous regression of up to one quarter of

neuroendocrine tumours has also been reported, albeit

most were extracranial in location, possibly due to host

immune response against neoantigens expressed by the

tumour.[13] This further increases diagnostic confusion, as

in our patient, and led us to interpret the regression of

lesions as a partial response to antiparasitic treatment.

Other imaging modalities such as PET scan may

offer more diagnostic clues, but 18F-FDG, which is

the most common tracer, may not show uptake in well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumours. On the

contrary, Ga-68-DOTATATE has a high sensitivity and

specificity in the detection of neuroendocrine tumours.[14]

Contrary to 18F-FDG which targets glucose metabolism,

Ga-68-DOTATATE targets somatostatin receptors that

are usually overexpressed by neuroendocrine tumours.

Nonetheless, this tracer is not yet widely available in our

region.

With hindsight, there are lessons to be learnt from

our patient and improvements to be made, especially

in her management. There was an 11-month period

(between 5 and 16 months posttreatment) with

no imaging follow-up or further workup. There were

already significantly enlarging lesions on the 5-month

posttreatment scan, and although present, regression of

the temporal lesions was subtle. More aggressive follow-up

imaging (e.g., within a few months) would have been

appropriate.

Furthermore, brain parenchymal haemorrhage, which

was already present on her initial MRI scan, is an

uncommon finding in neurocysticercosis. Alternative

differential diagnoses should have been considered,

especially in view of the suboptimal radiological

response to antiparasitic treatment. Given the vital

location of the enlarging lesions, further investigations

such as brain biopsy should also have been considered

and offered at an earlier stage.

Although treatment trials with antiparasitic drugs and

interval follow-up scans may provide a general idea of

the course of the disease, histological diagnosis including

excisional biopsy may be the only means by which to

confirm a diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

Neurocysticercosis in our region is uncommon, and

neuroendocrine tumour of the brain is even rarer. We

encountered an atypical presentation of a neuroendocrine

tumour of the brain mimicking neurocysticercosis. A

multidisciplinary approach involving the infectious diseases team, as well as neurosurgical and oncological

specialists, is necessary to reach definitive diagnosis.

REFERENCES

1. Caro-Osorio E, Perez-Ruano LA, Martinez HR, Rodriguez-Armendariz AG, Lopez-Sotomayor DM. Primary neuroendocrine

carcinoma of the cerebellopontine angle: a case report and literature

review. Cureus. 2022;14:e27564. Crossref

2. Porter DG, Chakrabarty A, McEvoy A, Bradford R. Intracranial

carcinoid without evidence of extracranial disease. Neuropathol

Appl Neurobiol. 2000;26:298-300. Crossref

3. Deshaies EM, Adamo MA, Qian J, DiRisio DA. A carcinoid tumor

mimicking an isolated intracranial meningioma. Case report. J

Neurosurg. 2004;101:858-60. Crossref

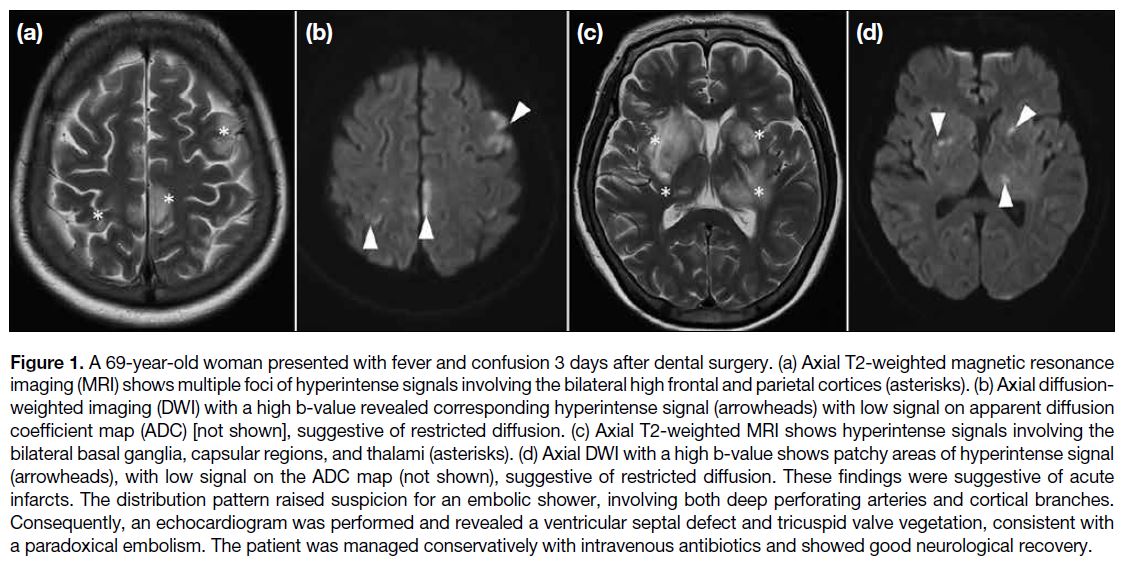

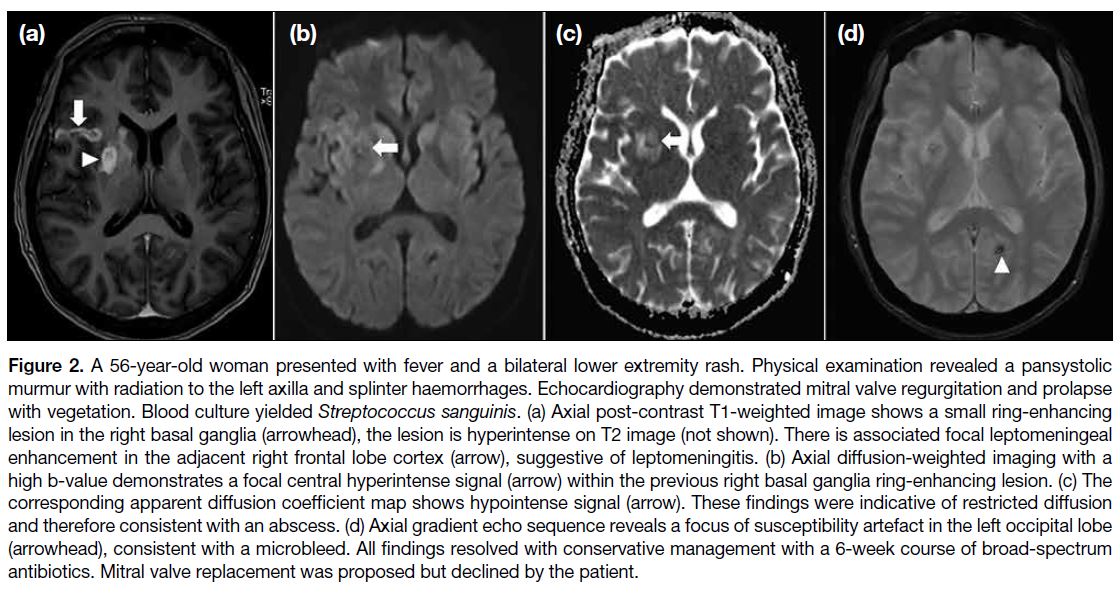

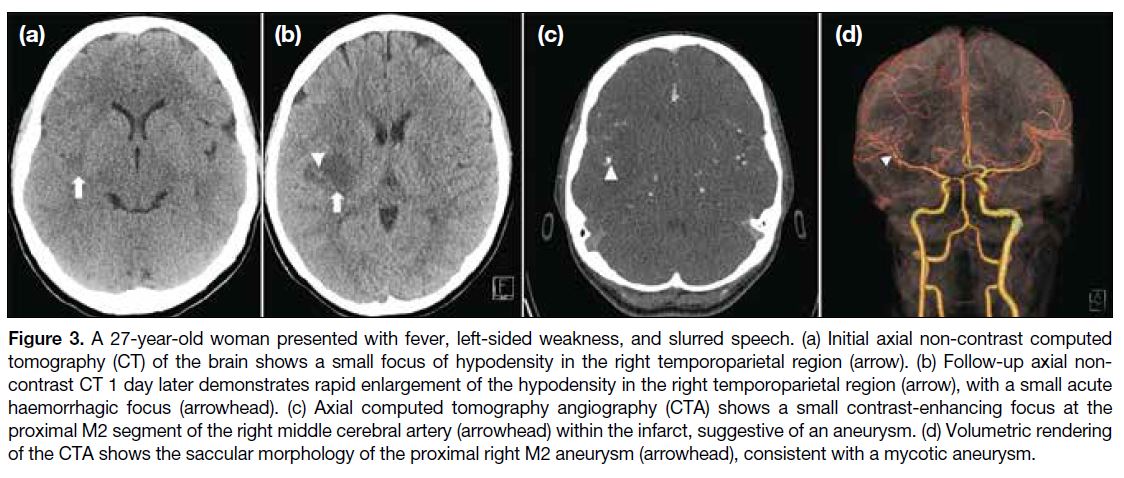

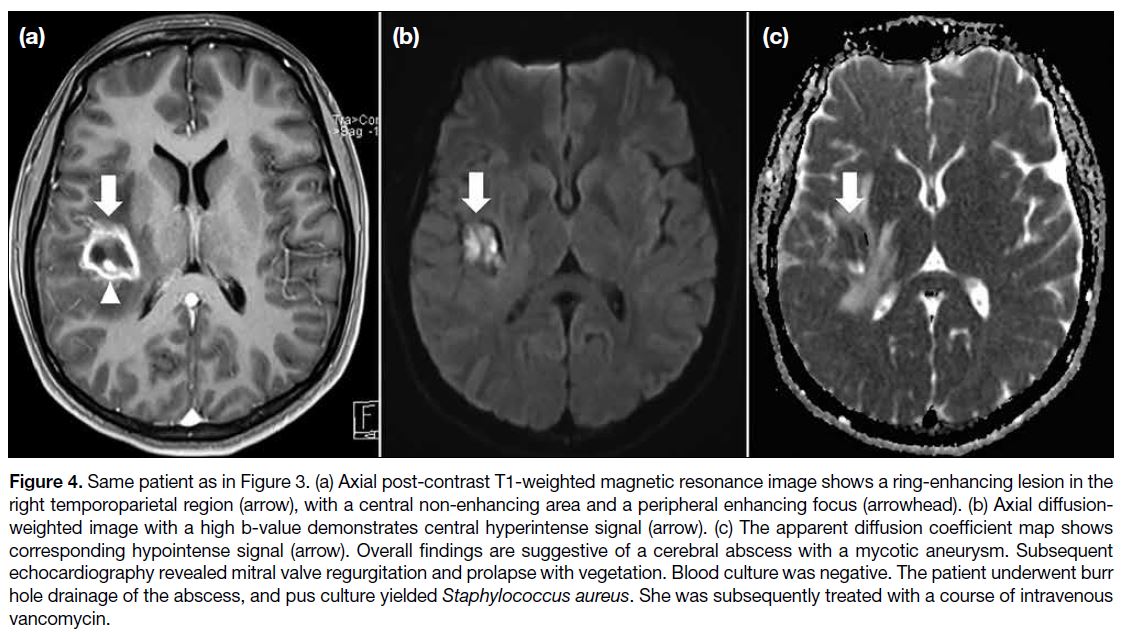

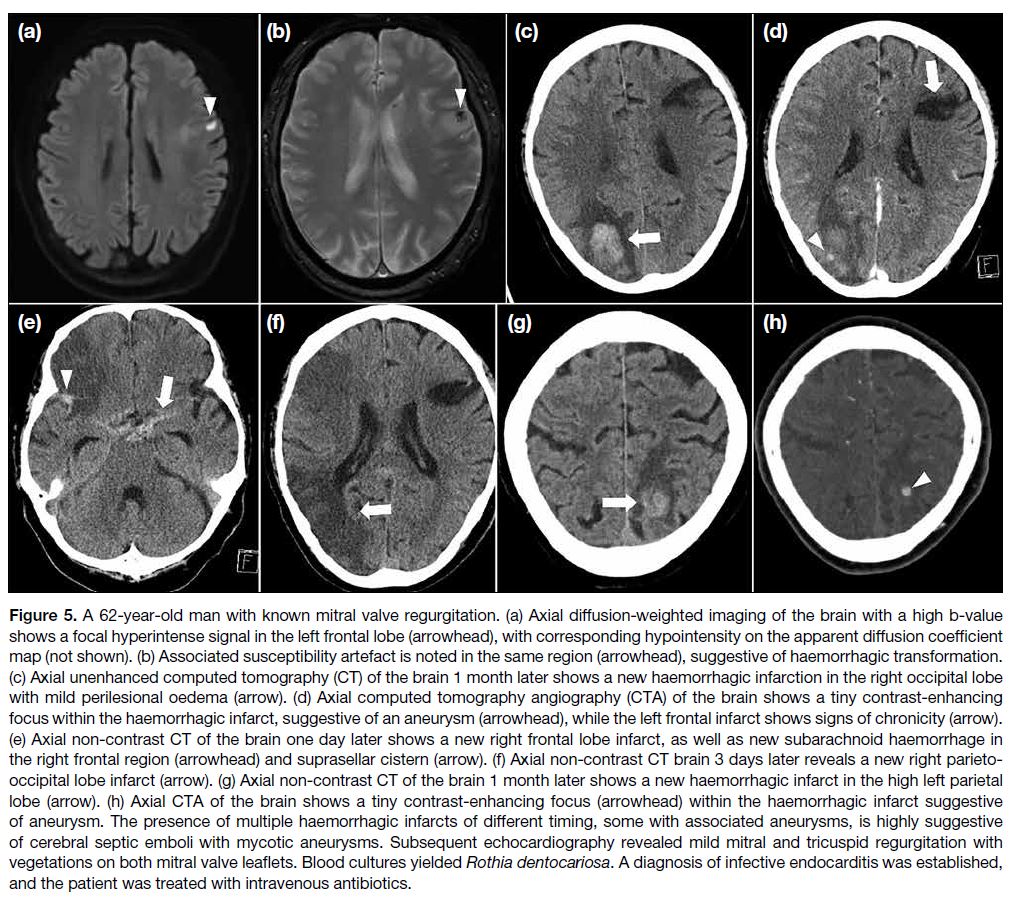

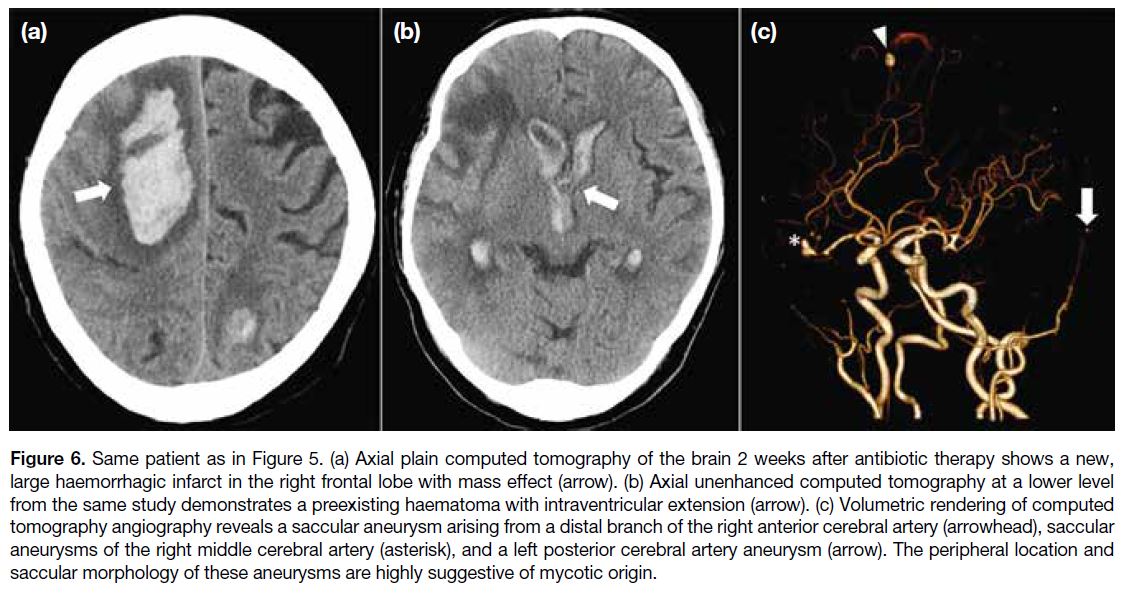

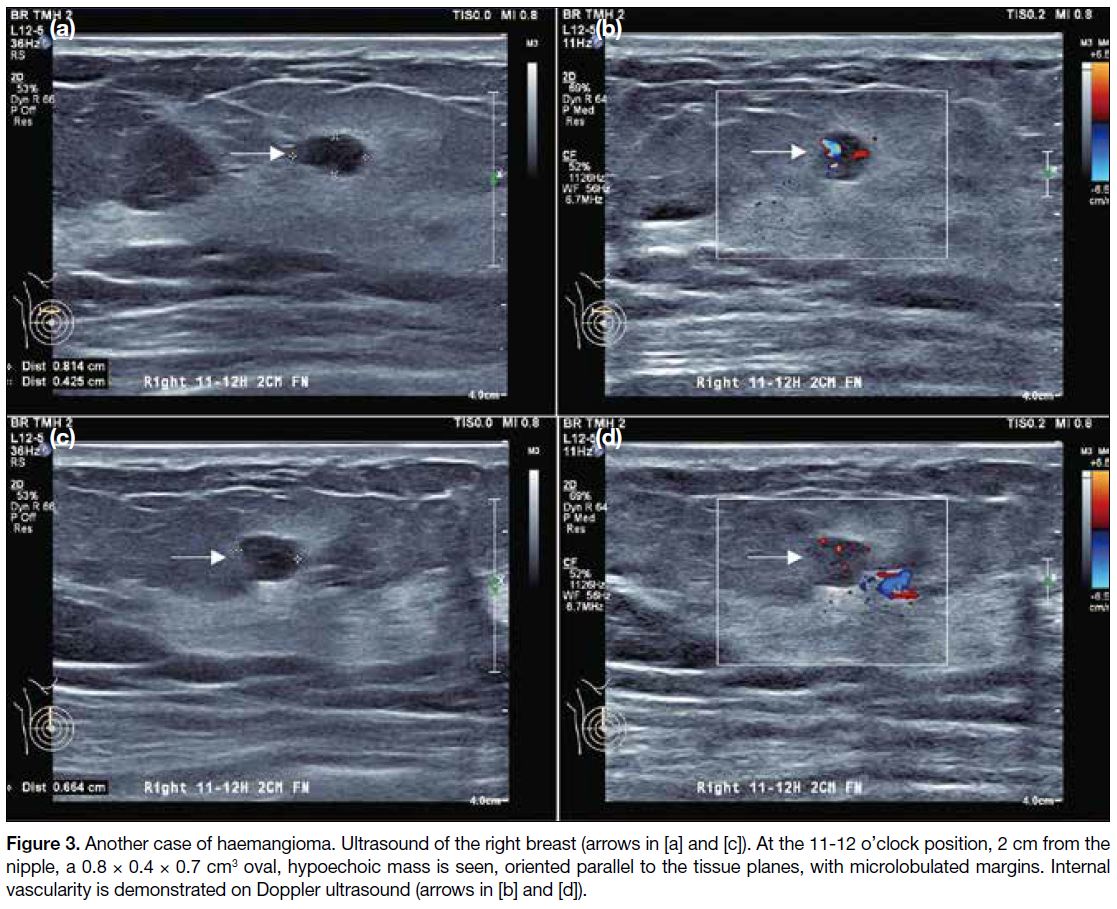

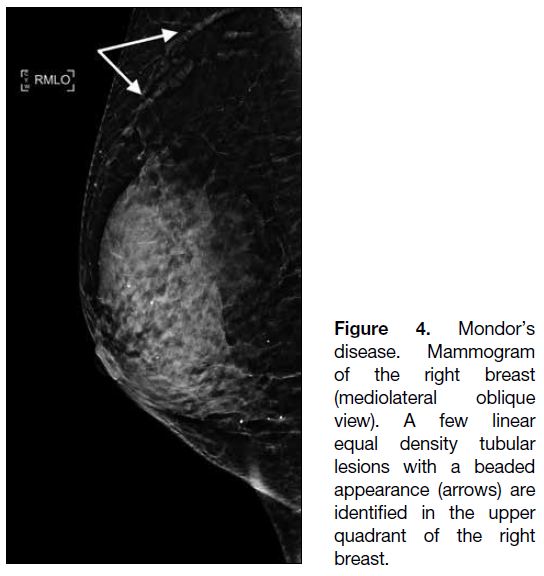

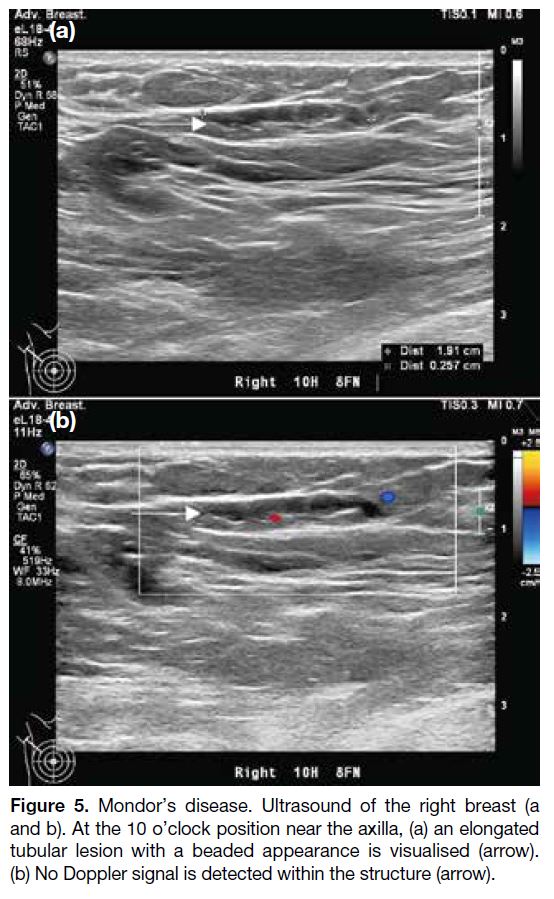

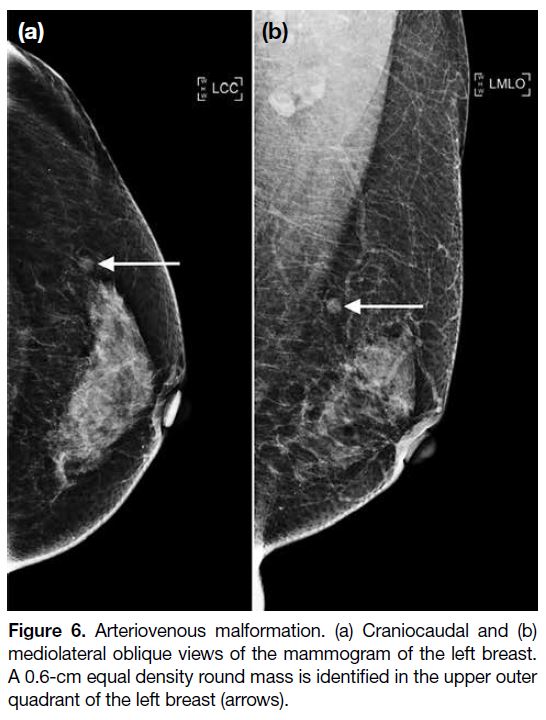

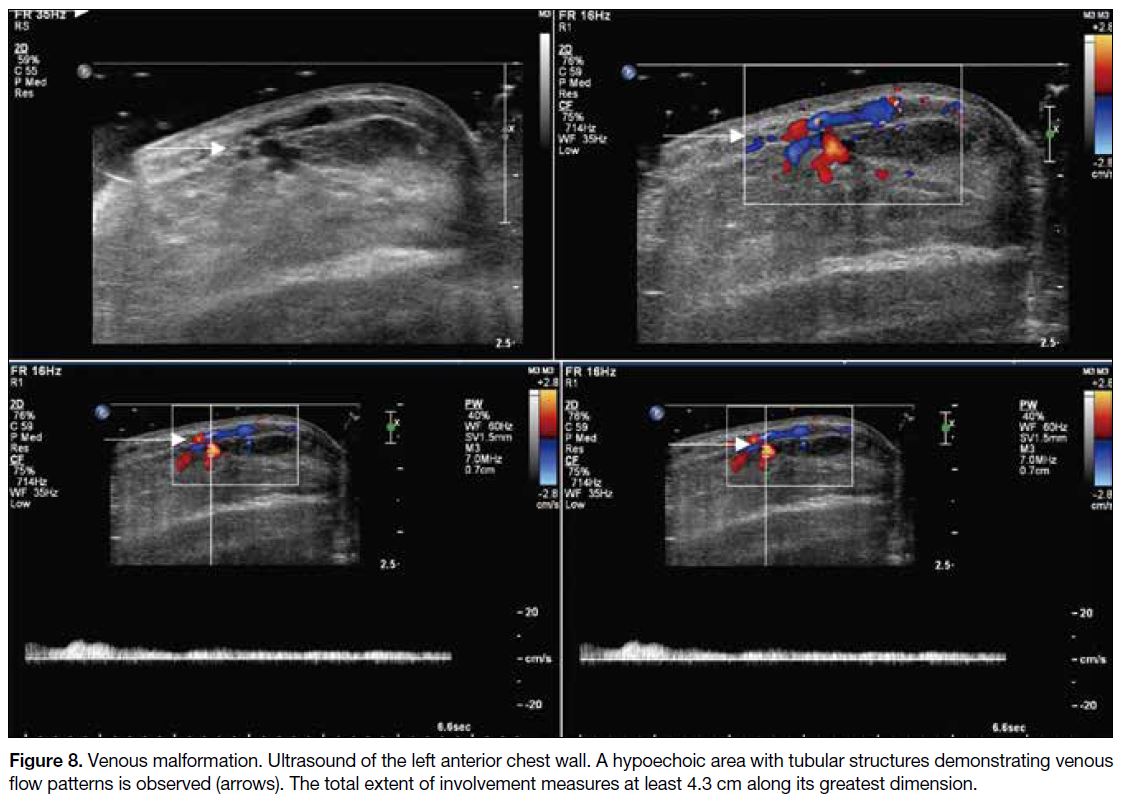

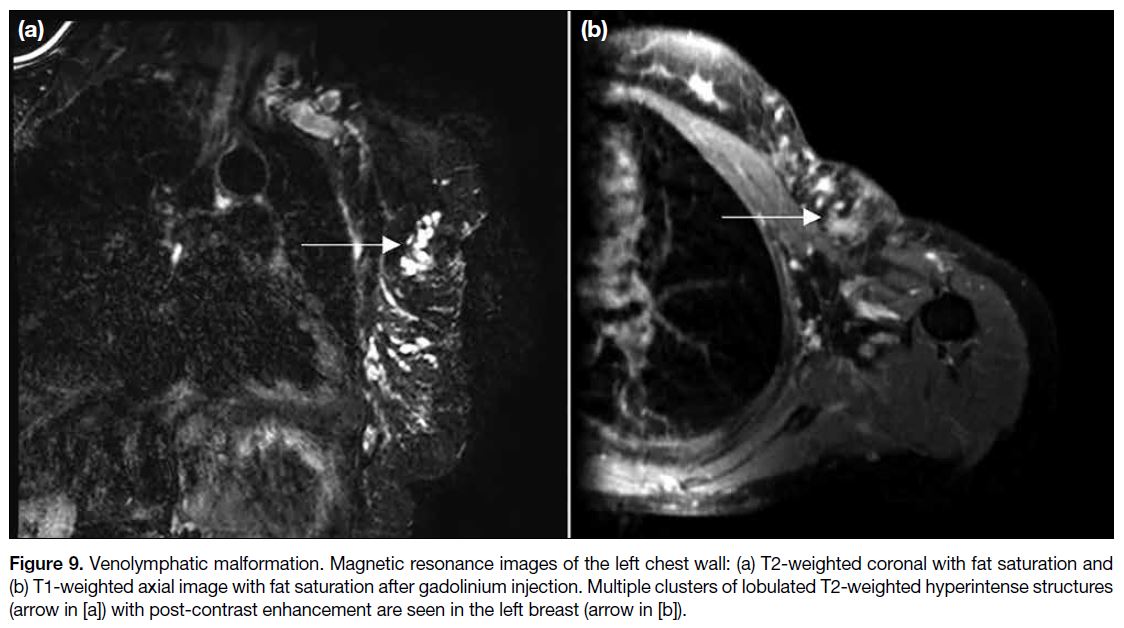

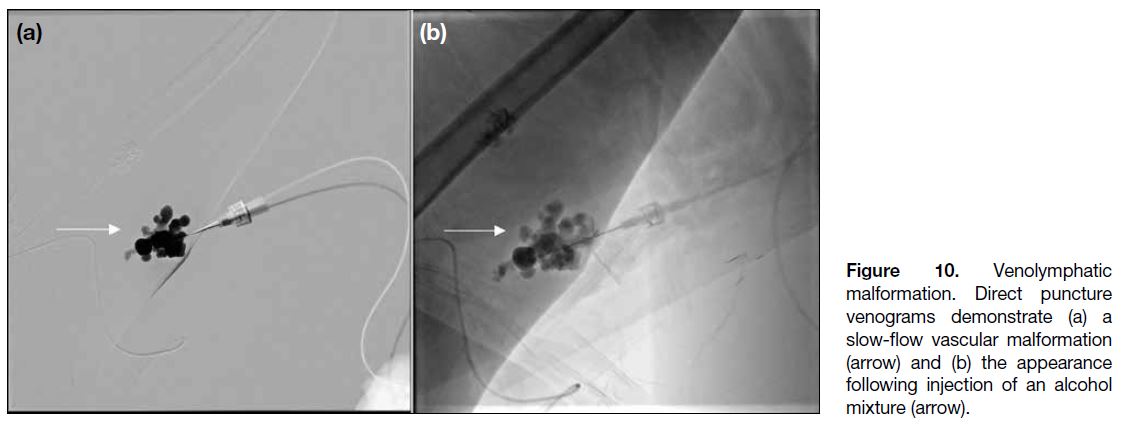

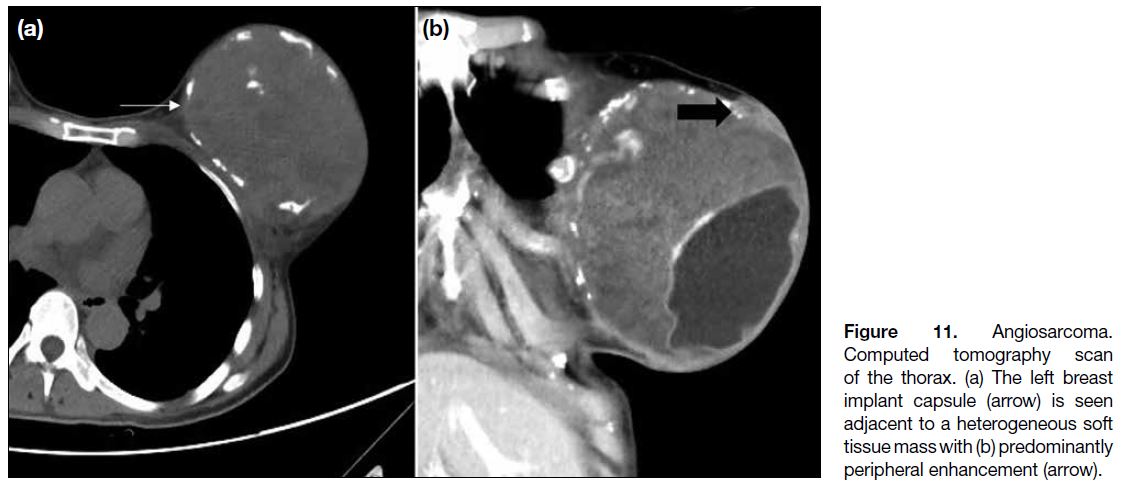

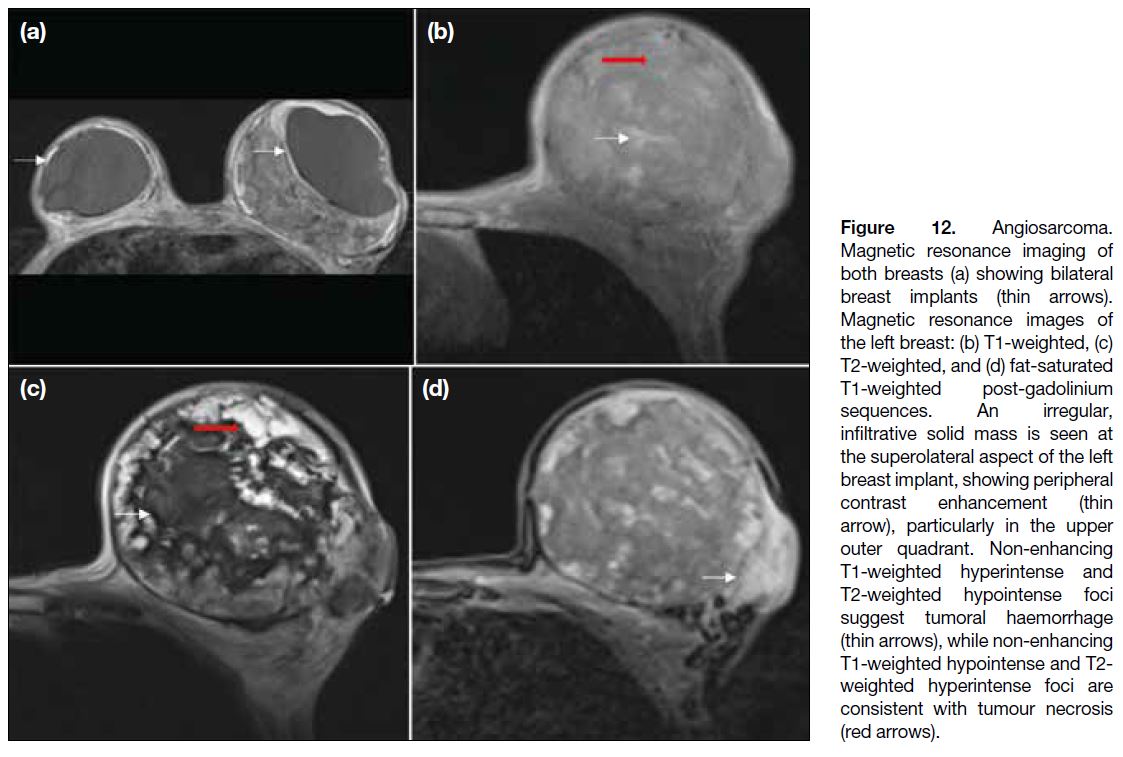

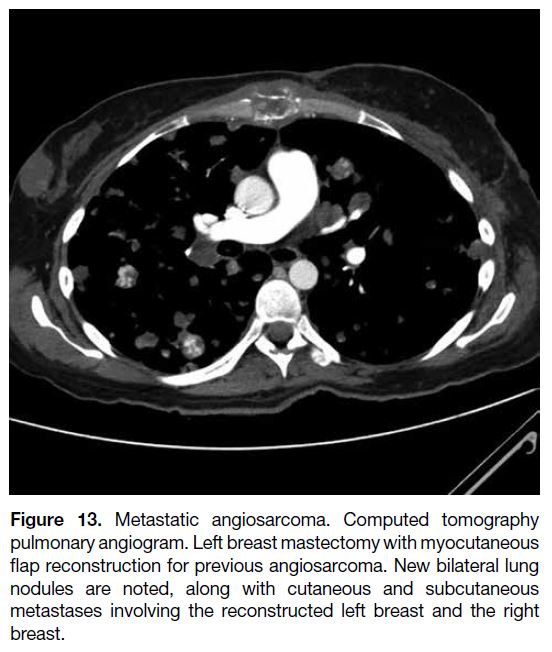

4. Ibrahim M, Yousef M, Bohnen N, Eisbruch A, Parmar H. Primary